When The Beats Came Back

How a 1956 road trip by Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder ’51 shaped “Howl,” and left Reed with the earliest-known recording of the epic.

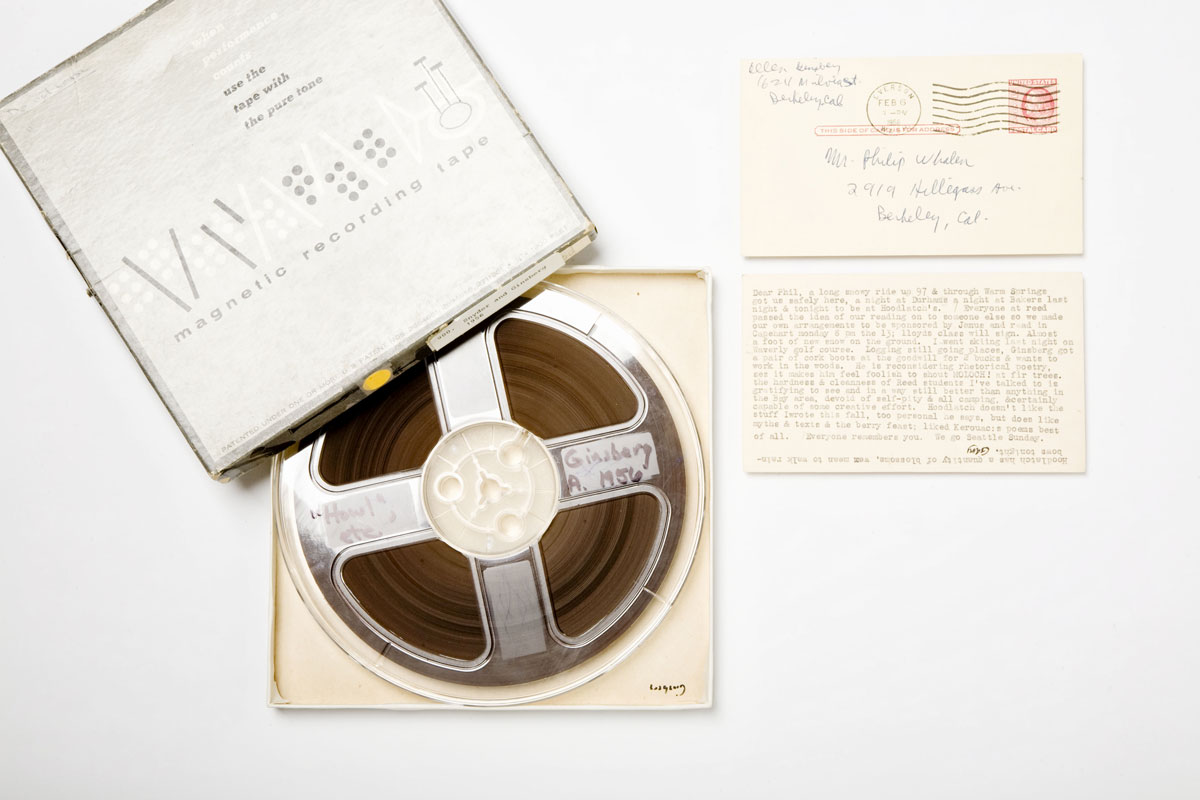

In a plain gray archival box in the basement of Reed’s Hauser Library there lies a single reel of audiotape that captures a moment in the early life of one of the anthemic poems of the 20th century. The aging brown acetate clarifies an author’s voice, hints at a spirit, adds to the myth of two poets, and tells of a part Reed College played in the early days of the Beat Generation—before it was Beat, or yet a generation. The lid of the box is marked simply but evocatively with two names and a year: “Snyder Ginsberg 1956.” It has lain there, duly cataloged but unlistened-to, until this past spring, when I stumbled on it (with the help of Reed archives assistant Mark Kuestner) in the course of research for my biography-in-progress of Gary Snyder ’51.

Inside the box, the reel labeled “Tape 2” contains the earliest-known analog recording of Allen Ginsberg reading his groundbreaking poem “Howl.” (Where is Tape 1 and what does it contain? We didn’t know until a Reed alumnus walked into the archives following news reports of this story. He had a cassette copy of the original reel-to-reel tape, containing Snyder reading his poetry in February 1956.) Tape 2 also includes pristine early recordings of several other shorter Ginsberg poems. The tape—of superb clarity and sound quality—was made at a poetry reading given on campus in mid-February 1956, when Ginsberg and fellow poet Snyder passed through Portland in the course of a three-week hitchhiking trip from Berkeley to the Pacific Northwest.

“Howl” exploded like a year-long double starburst over the cultural landscape of the Bay Area in 1955 and 1956. The first pop sounded at a now-famous public reading in October 1955 at the Six Gallery, a hole-in-the-wall art space in San Francisco; the second and much louder blast came a year later when Howl & Other Poems was published in book form by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights press, and was subsequently busted for obscenity, becoming a literary cause célèbre and spreading Ginsberg’s fame worldwide.

But all that was further down the road when Snyder and Ginsberg blew into Portland in mid-February 1956 for a reading at Anna Mann Cottage. Ginsberg was still a complete unknown outside the small poetry world of the Bay Area. That winter’s jaunt was very much Snyder’s trip, with Ginsberg along for the ride. After years of wily subsistence and dogged self-preparation, Snyder had just landed an $85-per-month stipend from the First Zen Institute of America to go to Kyoto, Japan, for a year of translation work and introductory Zen training, with an eye toward a much longer stay if all worked out. He had gotten his passport, and would soon buy a one-way steamship ticket for Kobe.

At age 25, it was the beginning of a new life, but it was also the end of a long chain of effort that went straight back to Reed. The hitchhiking trip with Ginsberg was for Snyder a restless farewell tour of sorts—a chance to visit scattered Reed friends and take in old haunts and beloved Northwest landscapes that he would not see again for some time. For exactly how long, he wasn’t sure—as it turned out, he would spend most of the next 12 years in Japan.

For Ginsberg, who’d only been on the West Coast a bit more than a year, this was his first trip to the Pacific Northwest—and the first of many journeys with Snyder in years to come. At that time Ginsberg knew little of the West, or of Snyder, for that matter. They’d met in Berkeley just four months before at the urging of Kenneth Rexroth—Snyder’s poetry mentor at the time—who also knew Ginsberg and suggested that they meet. The two young poets hit it off from the start, and together organized the Six Gallery event, assembling a potent quintet of readers that in addition to themselves included the surrealist poet Philip Lamantia, the dashing Michael McClure, and Snyder’s old friend and former Reed housemate, Philip Whalen ’51.

Ginsberg’s explosive reading of “Howl” had been the pièce de résistance of the Six Gallery event, but he was not the final reader. Snyder, it turned out, had been the last of the poets on the night of the Six, taking the stage in the cathartic wake of “Howl.” No mean feat, and one that Snyder pulled off masterfully, by all accounts, guiding the riled-up audience from Ginsberg’s Passaic and Harlem river lamentations, to the songs and myths of the Deschutes and Willamette in “A Berry Feast” and other lyrics of logging and lookouting. Ginsberg had been enormously impressed by Snyder, both before and after the reading.

“Allen had respect for Gary in a way that he didn’t for some other people,” observed mutual friend and fellow Six-poet Michael McClure. “He wanted to learn from Gary—about nature, hitchhiking, mountain ways. These Eastern boys like Allen and Jack [Kerouac] finally got out here and got past North Beach, and discovered that there were forests and mountains and deserts and wildflowers…”

Finally, on their 1956 swing through the Pacific Northwest, Snyder and Ginsberg were on a mission to shake things up, to sound their newfound bardic voices over a farther range, and to spread the excitement of the poetry renaissance and the spirit of the Bay Area freedom.

When Snyder and Ginsberg arrived in Portland for their reading at Anna Mann Cottage on February 13, they’d been on the road for three weeks—riding squeezed into the cabs of gyppo rigs or rattling along in the back beds of pickups, or hiking for miles on foot with no rides at all against the vast landscape of the misty Cascades, like tiny figures in a Chinese scroll. If Allen had wanted to “learn hitchhiking” from Snyder, he’d gotten that in spades. And for Snyder too, the trip had been fruitful: many images and incidents from it would find their way into his famous road montage, “Highway Ninety-Nine.” Along the way they’d also given a couple of poetry readings, one in Seattle at the University of Washington—Ginsberg’s first full-length public reading of all four parts of “Howl”—and another at a party given by Dick Meigs ’50 and Janet Bright Meigs ’52, Reedies who’d settled on a strawberry farm northeast of Bellingham.

In Portland, Snyder and Ginsberg stayed with Snyder’s old friends Bobby and Alice Allen (née Alice Tiura ’52), who lived southwest of campus in big apartments cut out of the old clubhouse of the Waverly Golf Club. Alice (today Alice Moss) recalls, “We’d been drinking wine with dinner, and then we went over to Reed, to Anna Mann. The common room at Anna Mann has been enlarged since those days, so the older, smaller room felt pretty full, but I don’t think there were more than 20 people there.

“Allen read ‘Howl,’” Moss continues, “which was really very startling—stunning. I thought he started out like he was kind of drunk, and I wasn’t sure he was going to be able to carry it off, but he gained power as he went on. He had me both laughing and in tears some of the time.”

The next night, February 14, Ginsberg and Snyder read on campus again, this time unscheduled. It is unclear whether this second night’s reading was also at Anna Mann, or at another location—perhaps Capehart, where there was good sound equipment, and where the Anna Mann reading had originally been booked. No venue is listed on the tape reel or box. At any rate, it is from their second night that the library’s recording was made.

On the tape, Ginsberg begins reading without any opening remarks, going directly into a poem he introduces as “Epithalamion” (later published as “Love Poem on Theme by Whitman” in Reality Sandwiches). An epithalamion is a classical genre written for a newlywed couple. In ancient times, it was to be sung at the door of the bridal chamber to encourage fertility; but in this “Epithalamion,” the poet-singer doesn’t stay outside. He enters the room, peels back the bedsheets from the sleepers, and descends like a ravishing incubus between the bridegroom and the bride for a nocturnal ménage à trois. The poem is shudderingly erotic in its kinetic detail. When Ginsberg’s voice abruptly stops at the end of the poem, the stunned silence in the room is palpable on the tape, even at a distance of five decades.

Ginsberg then reads “Wild Orphan,” an early poem for his friend Neal Cassady’s abandoned son, Curt (“son of the absconded hot rod angel”); “Over Kansas,” from Ginsberg’s days as a market researcher and his earliest “airplane poem”; and “Dream Record”—a tender elegy addressed to the ghost of Joan Vollmer Adams, wife of William Burroughs, killed by gun-nut Burroughs in a drunken prank in Mexico a few years before.

Ginsberg next reads the short “Blessed Be the Muses,” thanking them for “crowning my bald head / with Laurel”; then, “A Supermarket in California”—his homage to his spiritual mentor and “courage teacher,” Walt Whitman.

Following “Supermarket” comes a poem Ginsberg calls on this tape “The Trembling of the Lamb,” which Ginsberg readers will recognize as a working version of “Transcription of Organ Music,” from Howl & Other Poems. (Ginsberg wrote an earlier poem titled “The Trembling of the Lamb,” unrelated to this poem.) For text scholars, this “Transcription of Organ Music / Trembling of the Lamb” will be perhaps the most interesting of the short poems on the Reed recording, differing considerably from its published version.

At this point in the reading, someone just off-mike (presumably Snyder) asks, “Do you want to read ‘Howl’?”

“I really don’t,” Ginsberg replies wearily. “I don’t know if I have the energy.”

To those familiar with Ginsberg’s later history with “Howl,” this reticence comes as no surprise. Though he loved to read the poem when he felt it was in him, he often refused requests for “Howl,” citing not only the physical and emotional effort each reading took, but also the “trap and duty” he felt the performance sometimes became. We may be hearing the beginning of that ambivalence on this recording.

From Ginsberg’s comments to the audience, it is clear that he’d read the poem on campus the night before and didn’t want “to go through all that again.”

At any rate, Ginsberg’s resistance is short-lived, and he decides to go ahead with the poem that he is still at this point calling “Howl for Carl Solomon.” Ginsberg would later drop Solomon’s name to a lower dedicatory line, leaving the poem’s title simply “Howl.” Solomon had been a fellow patient with Ginsberg at the New York State Psychiatric Institute in 1949–50; the poem is dedicated to him in psychic solidarity.

Before launching into “Howl” itself, Ginsberg pauses to briefly prime his listeners for what’s to come. “The line length,” he says. “You’ll notice that they’re all built on bop—You might think of them as built on a bop refrain—chorus after chorus after chorus—the ideal being, say, Lester Young in Kansas City in 1938, blowing 72 choruses of ‘The Man I Love’ ’til everyone in the hall was out of his head—and Young was also . . .” (This was pure Kerouac, straight from the prefatory note to Mexico City Blues, wherein Kerouac states his notion of the poet as jazz saxophonist, “blowing” his poetic ideas in breath lines “from chorus to chorus.”)

Ginsberg then begins with his now-famous opening line, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness . . .”—delivered in a rather flat affect. First-time listeners may be surprised at how low-key Ginsberg sounds at the outset of this reading of “Howl,” though this was typical, and soon enough his voice rises to what he later called “Hebraic-Melvillian bardic breath.”

“I still hadn’t broken out of the classical Dylan Thomas monotone,” Ginsberg later wrote of his early readings. “—the divine machine revs up over and over until it takes off.”

The Reed recording of February 1956 is superb, faithful in pitch and superior in sound quality to any presently known 1950s version. Allen is miked closely, so his volume is even throughout. His enunciation is clear, his timing perfect; he never stumbles. His accent is classic North Jersey Jewish, intelligent and passionate. The poet-as-saxman metaphor comes demonstrably true as we hear Ginsberg drawing in great breaths at the anaphoric head of every line. It’s a recording to be breathed with as much as listened to.

There are technical problems with the tape, to be sure. Though Ginsberg reads the entire Part I of the poem, he abruptly ends the reading four lines into Part II, the “Moloch” section, saying only (again, presumably, to Snyder, off-mike), “I don’t really feel like reading any more. I just sorta haven’t got any kind of steam, so I’d like to cut, do you mind?”

The reading abruptly ends, leaving one to wonder if there were not more to Ginsberg’s hitting the brakes on Moloch in this reading than simply a lack of energy or annoyance with tape glitches.

The Moloch section of the poem, in which the poet names the destroyer of the “best minds” litanied in Part I,was a later addition to the poem and went through more revisions than the other main sections. Altogether, there are 18 known drafts of Moloch. Ginsberg may not yet have had total confidence in it. Snyder, in a postcard to Philip Whalen, hints at this when he writes, “He [Ginsberg] is reconsidering rhetorical poetry, sez it makes him feel foolish to shout MOLOCH! at fir trees.”

What is certain is that the Moloch section of “Howl” was in revision during the time of this 1956 trip, and the responses Ginsberg got from his various audiences along the road helped with his editing decisions as Part II took final shape. Alice Moss recalls students quizzing Ginsberg intensely about the meaning of Moloch. “Was Moloch the embodiment of ravenous capitalism? Was it a metaphor for some broader spiritual decay of the West? A cultural monolith? What? Everybody wanted to know what he meant,” she recalls. “And Allen said, ‘It’s all of those things—and more.’”

The “Howl for Carl Solomon” that Ginsberg read at the Six Gallery in October 1955, it should be noted, differed greatly from the poem published a year later by City Lights. The published poem is a four-part work; at the Six, Ginsberg read only Part I. Parts II & III and the “Footnote to Howl” hadn’t yet been added. Part I, the longest single section, initially entitled “Howl for Carl Solomon,” underwent several drafts before publication. The whole poem was still in the cauldron, as it were, a public work-in-progress for nearly a year as Ginsberg read it before a number of audiences in late 1955 and early 1956, revising and redrafting as he went. Reed’s “Howl,” falling midway between first reading and final publication, is very much part of that process.

So, where does the “Howl” on Tape 2 in Reed’s Hauser Library fit in? Ginsberg scholars are familiar with five separate typescript drafts of “Howl Part I,” organized by Ginsberg himself in a 1986 variorum edition of the poem. Reed’s “Howl” most closely matches up with the typescript that is known as “Part I / Draft Five.” (Following along on the tape using the variorum edition, listeners will actually hear Ginsberg turning the pages of his typescript at the same moment that they are turning the facsimile pages in the book.) Even so, there are more than two dozen variations between Reed’s tape and the Draft 5 text. From a scholar’s point of view, Reed’s recording, with its text variations, ancillary remarks, and historic significance, is a treasure trove. Some of the differences are very minor, but others involve resequencing or deletions of long lines, and significant word substitutions and additions.

What’s more to the point for the general poetry listener or Beat Generation aficionado is how the Reed tape compares with the previous earliest known recordings. No tape has ever surfaced of the October 1955 Six Gallery reading, and it’s likely none was made. The Six Gallery, by all accounts, was a refreshingly unselfconscious event. No one even thought to snap a photograph of the “remarkable collection of angels” on the stand that night, a roster that included not only Ginsberg, Snyder, Whalen, McClure, and Lamantia, but also master-of-ceremonies Kenneth Rexroth and Jack Kerouac—Kerouac not reading, but perched on the edge of the stage in winejug solidarity with the poets, in his own private space midway between them and their audience.

Then again, why should there have been photos or tapes at the Six Gallery? Except for Lamantia—and Rexroth, of course—none of the poets had ever read publicly before that night. No one in the audience suspected that they were in for an epochal event.

Only Snyder, it turns out, had an inkling of what was about to happen. Shortly before the event, he predicted to Whalen, “I think it will be a poetickal bombshell.” In his journal he confided, “Poetry will get a kick in the arse around this town.” Immediately after the reading, he reportedly told a friend, “Save the invitation. Someday it will be worth something.”

The Six Gallery event became a legend in short order—not just for “Howl,” but for the whole five-shot salvo from the gang of poets. Within weeks, each of them was invited to give readings around town. “From that night on,” said Snyder, “there was a poetry reading in somebody’s pad, or some bar or gallery, every week in San Francisco.”

Then, in early 1956, Thomas Parkinson, a literature professor at UC–Berkeley and one of the first academics to grasp the broader cultural significance of the emerging Beats, organized a reprise reading for the Six Gallery poets, with Rexroth again as emcee, for people who had heard of the October ’55 event but missed it. This encore reading was held at the Town Hall theater in Berkeley on March 18, 1956.

It is from that event that the earliest-known audiotapes of “Howl” were made, and which Reed’s “Howl” now leapfrogs in the queue of literary history. From the perspective of 52 years, five weeks might not seem like much, but there are some notable differences between the Reed and Berkeley recordings, both in the content of the tapes and the ambience of the events.

Most significantly, at the Berkeley reading, Ginsberg delivered the entire four parts of “Howl.” For that reason alone, the Berkeley tapes are historic, regardless of technical drawbacks. As it turns out, it is precisely on Part I of “Howl” at Reed (the only part he completed) that Ginsberg’s reading shines most.

At Berkeley, the poets’ burgeoning notoriety preceded them, and the audience was raucously expectant—a little too raucous for Ginsberg at the start. On the tape, you can hear that several people in the audience are clearly hammered—whoopingly so; others are camping it up for the microphones; everyone seems giddy with anticipation of “an event.” Rexroth, the emcee, sounds a little sloshed himself, and a bit too “on.” Early in his reading, we hear Ginsberg admonishing the crowd: “I’d like to read this without all the hip static,” and finally, “all right now, cut the bullshit!”

At Reed, of course, there is none of that. For one thing, there’s no “scene” on campus or in Portland to speak of (though Snyder and company sometimes called it “Poetland.”) On campus, Snyder was well-remembered by faculty members such as Lloyd Reynolds and David French, but was hardly a household name among students (yet); Ginsberg was completely unknown. In the campus Quest, the listing tellingly omits their names, indicating only a “Poetry Reading, 8 p.m.” at Anna Mann. Their relative anonymity allowed them to observe and interact with their listeners in a way that was fast becoming impossible in the Bay Area. While in Portland, Snyder commented on these differences in a postcard to Whalen, who was back in Berkeley. “The hardness and cleanness of Reed students I’ve talked to is gratifying and in a way still better than anything in the Bay Area, devoid of all self-pity & all camping, & certainly capable of some creative effort.”

So, might another tape surface to supplant the one held by Reed’s library as the earliest recording of Ginsberg’s “Howl”? Probably not. Then again, America’s brief literature is already replete with examples of “newly found manuscripts,” and, given enough time and chance, even the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Songs of Milarepa eventually came to light. For now, let’s just think of this recording as a clear sweet slice in the compositional life of a great 20th-century poem, an acetate howl coming to us chorus after chorus out of the ether, an aural visitation from the Beat Generation.

John Suiter is the author of Poets on the Peaks: Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Jack Kerouac in the North Cascades. He is currently at work on a biography of Gary Snyder.

Tags: Alumni, Books, Film, Music, Reed History