"Unorthodox" dean, inspiring correspondent

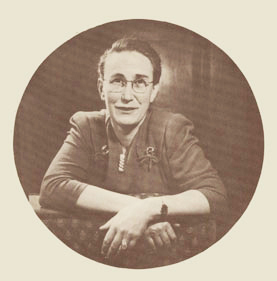

Ann Westenhaver Shepard ’23

Ann Westenhaver Shepard ’23, February 15, 1972, in Portland, following hospitalization for a long-standing heart condition.

Ann was the daughter of E.H. Shepard, orchardist and editor of Better Fruit magazine, and Alice Failing Shepard. She was born in Portland, and at age one moved with her family to a 40-acre apple ranch in lower Hood River Valley, living there until age 16, when her father died. She moved with her mother and four younger sisters—including Elsie Shepard Patten ’33, Henrietta Shepard Plueger ’35, and Lucy Burpe Shepard Howard ’37—to the Failing household in northwest Portland.

Further biographical notes come from Ann, in these thoughts shared with her retirement home, Holladay Park Plaza in northeast Portland, in 1968:

“Schooling was a patchwork of lessons at home on the farm, a year or two at old Couch School, the same in the Hood River County High School, and the last one and a half high school years at Miss Catlin’s School for Girls in Portland. From none of these educational efforts did this student emerge with a certificate or diploma like everyone else’s. But Reed College wasn’t full and in 1919 I entered as a freshman, invisible among the khaki pants and shirts of the demobilized young men who had just finished making the world ‘safe for democracy,’ and in June 1923, I was graduated as a major in comparative literature, and my diploma was exactly the same as all the others!

“Then to secretarial school and to work as a lowest flunky for the Ladd Estate Company (1923–26). Whenever any student wails about how dull office work is, I remember with profound gratitude the bits of real estate law I learned from the young legal clerk. Much of it is gone, of course, but I think I could still make an acceptable affidavit if pressed. In 1926, Reed College beckoned like a siren and about 44 years are accounted for. I was administration secretary, recorder, assistant registrar, dean of women, and for the last 25 years, dean of students (men and women). Something of a general wastebasket for whatever needed doing. Now I find myself very happy to sit down comfortably at Holladay Park Plaza and let someone else pick up the job I love so well.”

In addition to the National Association of Women Deans and Counselors, Ann's affiliations included the Oregon Association, Deans of Women and Girls; the College Personnel and Guidance Association; the Association of Foreign Student Advisors; the Urban League; the Reed alumni association; and the Episcopal Church. She held only one other position outside of Reed, that of clerk in the State Accident Commission in 1931–33. Josephine Grannatt Davis ’41, assistant dean of students (1953–63), edited Ann's letter for the book Yours Sincerely, Ann W. Shepard: Letters from a College Dean (Reed College, 1978).

On the occasion of Ann's retirement in 1968, the National Association of Women Deans and Counselors recognized her 25 years as a dean and 35 years at an educational institution with the following citation:

“Ann Westenhaver Shepard defies neat categories. For 25 years, she has unwittingly confused the role-definers and without doubt she has devastate the pet theories of questionnairing quantifiers. When she first began to meet with the Oregon Deans’ Association, which she served as treasurer and president, she was immediately identified as ‘the Unorthodox Dean.’ And such she was.

“In 1943, she was appointed dean of women, but when as many men as women came to her office, Reed College recognized the fact by making her dean of students. When she was later joined by a male colleague, Miss Shepard’s logic with regard to the role of deans in a coeducational institution prevailed: her associate’s office was not limited to men, nor hers to women.

“Since the deans at Reed College are not administratively responsible for student group activities, Miss Shepard has been able to maintain her role as one primarily advisory. Her success as an adviser cannot be attributed to professional training in counseling and guidance, in normal and abnormal, group and social psychology. However, it is important that, as a graduate (1923), as faculty secretary (1926–31), recorder (1933–43), and dean (1943–68), she has been intimately connected with the college for 45 of its 57 years. From faculty and students she has commanded a warm respect and deep affection and has represented the wisdom, serenity, and dignity, which is associated with the concept of an ordered world.

“From these vantages, she has acquired a remarkable perspective, a rare understanding of change, and, so far as anyone would know, she has never been surprised by its manifestations. She has the capacity to listen—that too often neglected other side of communication. Her advisees, whether faculty or students, have found in their experience with her (and long before it became a principle of counseling) that they had in part solved their problems in explaining them to her.

“Because Miss Shepard is extremely wary of generalizations, problem students have never been cases. She asks questions where others make speeches. She makes no pronouncements, which she must stubbornly justify or from which she must retreat. But when she chooses to make a statement, her conviction is clear and firm; the seemingly intractable suffer a quick thaw. A member of the science faculty, who sat with her on numerous committees, and with her endured perennial crises, has described her as a ‘catalyst for the meeting of minds under the most difficult conditions of interaction.’”

A Reminiscence of Ann Shepard by Josephine Grannatt Davis ’41

With the death of Ann Westenhaver Shepard, the Reed community lost one of key strands in its intricate human fabric. Because of her long association with the college, beginning as a freshman student at Reed in 1919, culminating with her retirement as dean of students in 1968, it is easy to fall into the sentimental Mr. Chips syndrome. We all regret the loss of so valuable a link wit the past and Ann would be the first to admit that it was often very useful indeed to have known the college so many years, yet the loss to the community is not due simply to long experience at Reed and is far from fuzzy nostalgia.

Ann Shepard, with her depth, subtlety, and rare balance of warmth and detachment, was able to view the strange, terrible, wonderful, ever-changing world of Reed College, and the student floundering in it, without losing her cool or her mettle. He edge never dulled, her sensibility never blurred. She took responsibility for literally thousands of students over the years. She served them as friend and adviser in their problems with friends, family, faculty, work, and most especially problems with themselves. No authority was behind her. She could enforce nothing, yet she gave so much beyond professional duty—small personal loans, waiting in hospitals, getting up nights to bail students out of jail, and even taking young people on occasion into her home to live. No student did without her support if she knew it was needed.

Yet through all the years and despite the numbers of students, Ann was able to view each student as unique, his problem as his alone. Sometimes, and hardest of all, there was nothing she could do but listen and wait. Her patience enabled her to forgo the false feeling of accomplishment which precipitous action provides. “I must wait for a handle” was the term she frequently used; sometimes the handle never appeared. She subscribed to no psychological school nor counseling dogma. In one of her letters she wrote, “I have great impatience with what so many people seem to make of clinical psychology: a substitution of the explanation of a problem for the correction of a problem. I can believe that understanding the source or beginning of a situation must often be useful or helpful; but the ‘problem’ seems to me always a matter of the present, and any correction is surely a job for the present . . .” She did not impose theory on student problems, but looked instead for patterns. Her approach was fluid, innovative, creative.

As a truly gifted and creative person, Ann Shepard fit no convenient stereotype whatsoever. Although her outstanding characteristics are all too rare, they were clear enough: an unelaborate but profound courtesy, scrupulous truthfulness, a boundless trust both given and received, and, most conspicuous of all, a gift in the art of letter writing, preserved in her extensive and fascinating correspondence. Her skill and realism in dealing with people was recognized by all who encountered it. But what a mass of contradictions this woman presented!

How could anyone with such a knowledge and gift for the English language do such a good job of keeping her mouth shut? Imagine this, after a lifetime in an academic climate in which the closed mouth and intellectual humility are scarcely the norm.

How could anyone with such a passionate devotion to truth, both large and small scale, regardless of any uncomfortable consequences to herself, be so skillful at sensible compromise?

She was the most worldly and truly sophisticated of women, with a wry, unshockable wisdom that is legend, yet she spent almost all of her life on a small college campus in the remote Pacific Northwest. She never married, and her primary social arena was her close knit family.

Her appearance was somewhat formal and even austere, but the face-to-face visitor was instantly seized by the warmth of her quizzical brown eyes with their amused, almost mocking glint. Or was it conspiratorial? “We’re in this together, aren’t we,” as if she viewed her role as a partnership, not seeing herself standing righteously or censoriously outside the situation.

Ann’s office door was always open and unguarded—no appointment necessary. This was sometimes a nuisance, but encouraged the impulsive visit, so frequently the crucial one. She courteously and instantly dropped the work on her desk, leaned back comfortably in her chair, crossed her legs, and eyes smiling through a cloud of smoke, settled down to really listen as if this visitor were her only concern for the rest of the day.

Ann Shepard combined a realistic skepticism in theory with complete trust in action. She made the leap into ethical faith. To the irresponsible campus bad guy, she calmly gave the keys to her new car when he needed transportation. He met her trust. The car was back on time and freshly washed besides. In Ann the skeptical realist lived comfortably somehow with the believer in the ultimate perfectibility of Reed students.

Shortly before her retirement, Ann Shepard wrote to a dropout student: “I shall be very, very pleased to see you back with us. I do think it is a kind of education that fits you and that you are able to use. I know you wound yourself up a bit before you set off . . . but not to extent which would blight your picking up again to be the effective student you are able to be. And I think your period of . . . what? frustration? confusion? resistance: . . . whatever, was no more than what so many thoughtful, upright, but inexperienced young people get into—oftener in your day than in mine, and perhaps this says something about young people, and perhaps only something about the world you live in. I often think these ‘things’ are respectable experiences in spite of the delay they may cause, or of the importance of moving beyond them.”

Appeared in Reed magazine: online only

comments powered by Disqus

![Photo of Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2022/LTL-levich1.jpg)

![Photo of President Paul E. Bragdon [1971–88]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Bragdon.jpg)

![Photo of Prof. Edward Barton Segel [history 1973–2011]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Segel.jpg)