Understanding Reed’s Endowment

How it works, and why it matters.

The brilliant professors solving equations on the blackboard. The students deeply engaged in debating Plato’s Republic. The Gothic halls rising up from the mist. None of it would be possible without the mysterious source of energy that pulses through campus much like Iron Man’s arc reactor—yes, we’re talking about Reed’s endowment.

That endowment, combined with annual gifts from alumni, parents, and friends—plus tuition revenue—is fundamental to Reed’s operation. It allows Reed to offer financial aid, pay professors’ salaries, invest in student services, heat the classrooms, run the sports center, and bring up the footlights in the theatre. And yet whenever I find myself in conversation about Reed’s finances, I am struck by the misconceptions people often harbor about the endowment, especially what is and is not possible when it comes to spending it.

In the Beginning

The history of the college’s endowment stretches back to 1904, when Amanda Reed died, bequeathing her fortune to an “institution of learning.” The Reed Institute was funded in 1909 with the sum of about $3 million—worth more than $96 million today. This fabulous sum allowed the trustees to embark on an ambitious plan for the college, spending generously to construct grand buildings such as the Old Dorm Block and Eliot Hall, hire professors, and recruit a dynamic young president, William Trufant Foster.

But the halcyon days did not last long. In the mid-1910s, the economy of the Northwest sank into a deep recession. The value of Reed’s endowment, which was primarily invested in local real estate, dropped by half. Making matters worse, the rental income generated by the properties plunged even farther. Meanwhile, America’s entry into World War I in 1917 further exacerbated the financial squeeze by cutting enrollment. By 1918, Reed’s graduating class had shrunk to a mere 37, and the college was facing an operating deficit of $50,000. President Foster and the trustees appealed to Portland’s wealthy citizens for support, but met with a stony reception—Reed was perceived as a hotbed of pacifists and radicals. The college was in financial crisis.

Reed weathered the storm by slashing costs and launching a fundraising drive, which more or less set the pattern for the next 50 years. Whenever lean times struck, the college scraped through by appealing to supporters for cash or—as a last resort—selling off its dwindling stock of properties. By 1971, the value of the endowment had fallen to $4.4 million, barely the size of the annual budget at that time. This situation was unsustainable.

The Forest and the Trees

Imagine you own a stand of maple trees. There are two ways to earn money from a maple tree. You can chop it down and sell the timber. Or you can tap it and harvest the sap to make syrup. Chopping a tree down yields a big windfall, but then it’s gone forever. Tapping a tree produces less cash, but you can do it again next year. Moreover, if tapped with care, the tree will keep growing, and produce even more sap the next time around.

On a basic level, this is the directive behind an endowment. When donors give to the endowment, they do so with the caveat that the gift won’t be spent down. The money is given to the college to safeguard and grow, creating a dependable source of income for years to come. The trustees have a responsibility (and legal restraints) that limit how much can be spent each year—as well as how much risk they can take in investment decisions.

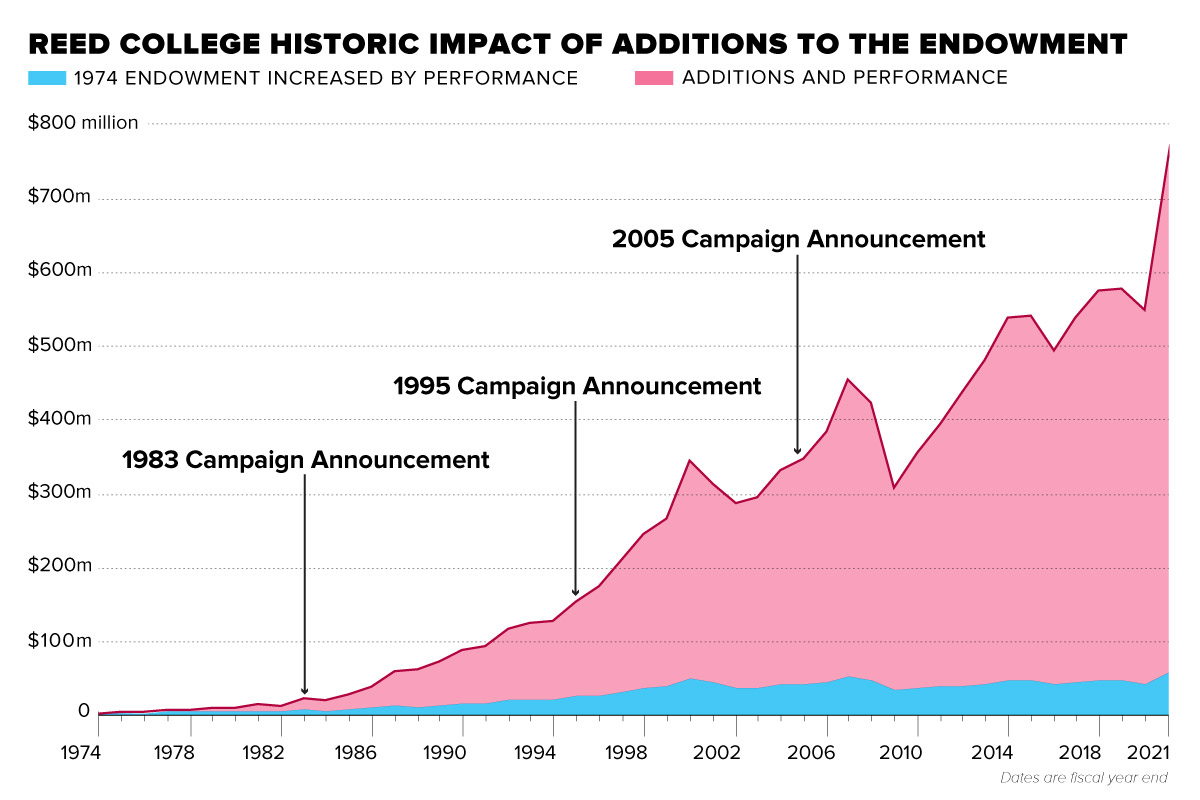

Reed’s current endowment is the result of decades of philanthropy, investment decisions, and discipline. As of June 30, 2021, its value stood at $779 million.

Endowment trustees at Reed and other institutions have flexibility in determining the percentage of investment earnings that can be applied toward current needs and a responsibility to preserve the endowment’s purchasing power for future generations. Reed trustees’ current policy is to withdraw 5% of the endowment’s value averaged over the prior 13 quarters. The purpose of the averaging is to smooth the levels of income received by the college, sustaining support for its programs in times of both rapid endowment decline and rapid growth. In the most general terms, schools invest with the goal of sustaining 8% in average growth over time. The assumption is that no more than 5% of this growth will be spent, leaving the remaining 3% to account for inflation.

Philanthropy Matters

Endowment earnings don’t run the college alone. The endowment and the Annual Fund are separate pools of money that work in tandem, providing 35% of the college’s operations, strengthening academic and student programs. Unlike endowment funds, Annual Funds can be spent fully in the year they are received and are available for use in areas of greatest need. For example, Reed is one of only a handful of colleges that commit to meeting 100 percent of the demonstrated need of all admitted students. As Reed builds more endowed support for financial aid, the Annual Fund can contribute to meeting critical need in the meantime.

Together, the Annual Fund and the endowment help the college grow less dependent on tuition revenue. The income generated by the endowment supports almost 30% of Reed’s annual operating budget, a percentage that has been slowly rising over the decades.

When the coronavirus spread across the globe in 2020, colleges saw precipitous drops in enrollment and simultaneously faced increased operating expenses. As a result of these pressures, many private liberal arts colleges cut staff, shuttered departments, eliminated faculty tenure lines, or closed entirely; thirty-five non-profit, four-year liberal arts colleges have closed in the last three years alone. According to the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO), 1200 colleges have closed in the last five years.

The Reed community responded to these uncertain times by generously making record-setting levels of Annual Fund gifts. These donations, along with the financial model that Reed has developed and implemented since the turbulent ’70s, made all the difference in supporting academic and student life programs as well as the college’s robust response to the pandemic.

The Bottom Line

The endowment boasted 40% growth over the past year. Investment strategy played a key role. But it is important to note that growth of this magnitude would not be possible without the many gifts to the endowment over the years.

You need only compare two scenarios to see why: without additions, since 1974 the endowment would have grown a mere 50 million dollars. Meanwhile, in our scenario, regular additions to the endowment have compounded over the years, increasing that performance by an extraordinary ratio. Ongoing contributions matter. Along with strong investing, philanthropy is important to ensure that the endowment retains its value, especially in the face of difficult circumstances such as changes in interest, inflation, downturns in the economy, pandemics, and more.

A dependable source of income like endowment interest helps Reed set long-term goals—build science labs, dormitories, and add faculty, to name a few. It allows the college to keep a low student-to-faculty ratio and to recruit students from a variety of backgrounds. It means the college can offer programs to support students during their time at Reed and take confident steps into their careers after college. The endowment, supported through philanthropy and careful management, means Reed can continue to offer a rigorous academic education, encouraging independent thinking for many generations to come—perhaps in perpetuity.

Tags: Institutional