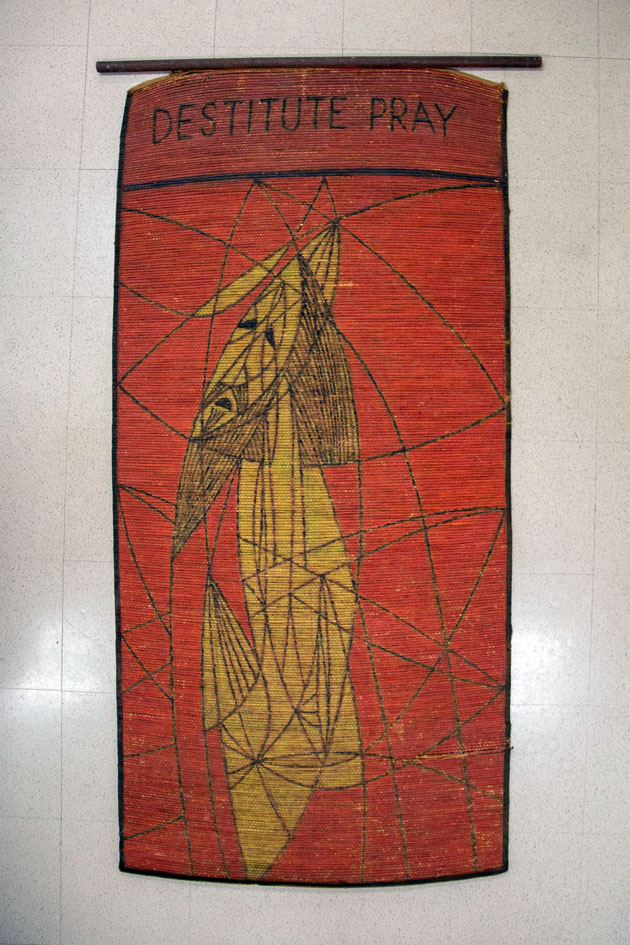

Destitute Pray

The true story of the enigmatic Reed artifact painted on a bathmat.

The recent death of Ruth Seitlin Grinspoon ’55 brought to mind her role in the saga of a vernacular painting which has kept me and other Reedies company for over 60 years.

Destitute Pray, as its legend reads, was painted by the artist Ed Stopke ’54 on the back of a six-by-two-foot straw bathmat in the fall of 1950 and has been handed down among Reedies ever since—long enough perhaps to qualify as a Reed artifact. When I moved to an old-folks home three years ago and had to downsize, Destitute was among my memorabilia accepted by the Reed archives.

The tale begins with Ed, who hailed from Detroit and came to Reed on a scholarship in 1950. He was an artist and a romantic who read stories by Jack London and John Steinbeck, and “dreamed of adventure on big rivers through deep forests lined by big mountains.” When he mentioned Reed to his scholarship sponsor at Detroit’s Cass Tech, she gave him a funny negative smirk and said, “Not that weird enclave of ‘commie’ influence?’” Ironically, that slur “gave me a great feeling that I had chosen just the right place,” he says. “I came to Portland and fell in love with Oregon and have never regretted it.”

The Freedom Was Contagious

Taking the train to Portland, he discovered that campus housing was tight—dorm rooms were in short supply—so he found lodging in a room above a lumber supply warehouse near the Burnside Bridge. It was “a perfect place—right on the riverfront, just across the street and down a short hill to the water—close enough to stake out two trotlines to see what I could catch for dinner,” he says. “Every morning from my large front window was a different picture of the Willamette River, a warship or a giant log raft with Mt. Hood always in the distance.”

He often walked across the bridge to collect coal for heat from the railroad tracks on the other side. “I spent many days with the hobos along the river,” he says. “They made good sketching subjects.”

Ed’s building was otherwise inhabited by Chinese-American families and he saved money for his rent by mopping the floor and taking care of the two toilets.

In an art class at Reed, Ed met Steve Gilbert ’52, a native Portlander who showed him around. “One evening,” Ed recalls, “ Steve took me to a houseboat colony. It was something we never had in Michigan despite the Great Lakes waterways. I don’t remember who we visited [[Prof. Stanley Moore and Marshall Watzke ’51 likely lived in Weber moorage then]] or why we went there. All I recall was the amount of driftwood (snagged for burning, perhaps from the sawmills on the river) and the orderliness of the walkways and street lights—like a little city.”

Ed soon discovered folk singing, protests and storytelling. Steve took him to “hoots” or hootenannies—informal gatherings under the Burnside Bridge. “I just ate all this up,” he says, and eventually bought himself a second-hand guitar and started practicing. “Portland offered me something new every day, from China, Japan, Europe, or out-of-the-blue. The migrant workers, hobos, wanderers or loggers brought all kinds of fresh spirit to what their native ancestors left behind. The freedom was contagious, almost as if Woody Guthrie would be around the next corner.” (Ed missed him by two years; Woody gave a concert at Reed in 1947.)

But facing the draft with strong pacifist views, Ed sought conscientious objector status and was never able to study more than a few months at Reed and the Museum Art School. Steve introduced him to the local American Friends Service Committee which arranged for him to avoid the Korean War by performing alternative service at a work project in Mexico.

Before he left, however, Ed painted Destitute on a straw mat and presented it to Steve as a gift. (Their memories differ regarding some details here. Back in 2000, before he died, Steve wrote to me that he “very well” remembered the day when he and Ed each painted a straw bathmat and gave each other their creations. But Ed has a different recollection—he remembers executing two versions of Destitute, a bigger and a smaller, and giving the smaller to Steve, who gave him a treasured edition of Tolstoy.) Either way, Ed departed for Mexico shortly thereafter to teach English in a remote village. He never returned to Reed.

Destitute’s Odyssey

Steve stayed at Reed, majored in art, and continued to spend time on the waterfront. As a teenager, he was too young to enter the shop of legendary tattooist Sailor George Fosdick, but he was able to press his nose against the window and soak in the salty ambiance. “On the walls were beautiful drawings of sailing ships, anchors, roses, dragons, eagles, snakes, and naked women. The whole scene seemed at once dangerous and fascinating,” he remembered. “The images on the wall spoke to me of travel, adventure, danger, and sex. In my impressionable young mind tattooing became indelibly associated with these things.”

After he graduated, he passed Destitute to his roommate Bob Richter ’51 in their off-campus apartment. For a brief time, Johnny Moses ’53 moved into Bob's apartment and then left abruptly—after which Bob doesn't remember seeing Destitute. Bob isn’t sure, but speculates Johnny may have taken it with him.

Bob also suggests that John Hotchkiss ’56 may have once had the painting, but John does not remember Destitute at all, although he may have seen “sketches that resemble it.” He once lived in an old building near the waterfront and also once lived with Johnny Moses. Could they have lived in the same building where Ed painted the mats?

So here is when Ruth enters the chain of custody. She told me she “definitely remembers” living with it in her Westport dorm room for a year but not how it came to be there. Her room was previously occupied by Geraldine Preston (Rasmussen) ’52, and Ruth speculated that Destitute may have been simply passed on with the dorm room.

When Ruth prepared to leave Reed for Mexico in the fall of 1954, she passed it on to me and my houseboat mate in gratitude for a roof over her head for a few weeks. That roof sheltered our mutual friend David Novogrodsky ’55 and me on a houseboat on the Willamette River. The boat, which we bought from Marshall Watzke ’51, struggled to stay afloat at what we called “Max” Weber Moorage near the west end of the Sellwood bridge.

The modest Weber Moorage (its space now occupied by the much fancier houseboats of Willamette Moorage Park) was home over time to many Reedies: professors Stanley Moore, Jack Dudman ’42, and Marsh Cronyn ’40; and Erika Zusi Munk ’60, Ahza Cohen ’57, Jonathan Ezekiel ’56 and Karen Kals Ezekiel ’56, Jan Doar Rondthaler ’55, Howard Rondthaler ’55, Abigail Mann Thernstrom ’58, and perhaps more beyond my fading memory.

When David graduated in 1955 and left town, Destitute finally devolved to me.

So I lived with Destitute Pray for more than 60 years, hanging it on my walls as I went from student to soldier, journalist, and professor, while living in different families in other houseboats, several Manhattan apartments and houses in Portland, Stony Brook (Long Island), Chicago, and Piscataway, New Jersey. With my early retirement from teaching in the mid-90s, Destitute and I both returned to Portland. And now, as Ed was happy to learn, it rests appropriately in the care of Reed, which attracted its creator and whose alumni preserved it.

Ed and his wife, Judy, are now retired and live in Michigan. “I don’t begrudge what life gives me,” he says. “But now one of my paintings could be hanging in the Reed archives, and I’m still active and still painting at age 87. Perhaps I’ll be called an honorary Reedie.”

As to the meaning of the enigmatic work, he explains that it embodies a sense of loneliness and want, together with an optimistic faith in the power of prayer. "I should have added a question mark after the word ‘destitute,’” he says. “The obvious answer is to pray.”

For myself, Destitute has been a talisman and link to my wannabe Beatnik/Bohemian youth and my Reed friends from the 1950s who I associate with it. I’m delighted its creator is now aware of its provenance. But despite what I now know about the artist’s intent, it remains most important to me because it expresses my Reed-begotten belief that especially for the destitute, dependence on prayer is not a sufficient refuge from a heartless capitalist world.

Tags: Alumni, Reed History