Hum 110 Final Exam - Fall SAMPLE

This is a closed book examination. For this as for all exams at Reed, the Honor Principle applies. You may not consult books, notes, or online materials for the duration of the exam. If English is not your first language, you may consult translation dictionaries.

Instructions:

This is a four-hour exam. Your work is due back, either in Vollum Lecture Hall or in your instructor’s electronic mail box, no later than Wednesday, December 12 at 12:00 noon (unless you have made prior arrangements for an accommodation).

The exam consists of three parts: Part One should take approximately one hour; Part Two, one and one-half hours; and Part Three, one and one-half hours. Save some time from each section for revision.

Part One (one hour): Select TEN, and ONLY TEN, of the following twelve quotations and images. Explain the significance of each of these quotations or images with respect to any of the following: the lecture in which it was discussed, the reading/work of art of which it is a part, and/or its cultural and historical context.

- One day, after Moses had grown up, he went out to his people and saw their forced labor. He saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his kinsfolk. He looked this way and that, and seeing no one he killed the Egyptian and hid him in the sand. When he went out the next day, he saw two Hebrews fighting; and he said to the one who was in the wrong, “Why do you strike your fellow Hebrew?” He answered, “Who made you ruler and judge over us? Do you mean to kill me as you killed the Egyptian?” Then Moses was afraid and thought, “Surely the thing is known.” When Pharaoh heard of it, he sought to kill Moses. (Exodus 2:11-15)

- The Athenians, however, far from losing their appetite for the voyage because of the difficulties in preparing for it, became more enthusiastic about it than ever, and just the opposite of what Nicias had imagined took place. His advice was regarded as excellent, and it was now thought that the expedition was an absolutely safe thing. There was a passion for the enterprise which affected everyone alike. (Thucydides,History of the Peloponnesian War, 6. 24)

-

‘And Enlil said: “Let Enkidu die, but let not Gilgamesh die!”

‘Celestial Shamash began to reply to the hero Enlil: “Was it not at your word that they slew him, the Bull of Heaven–and also *Humbaba? Now shall innocent Enkidu die?”

‘Enlil was wroth at celestial Shamash: “How like a comrade you marched with them daily!”’ (Gilgamesh, Tablet VII)

(Reconstruction of Pheidias, Athena Parthenos, by Alan LeQuire)

- This, then, is the version the Egyptian priests gave me of the story of Helen, and I am inclined to accept it for the following reason: had Helen really been in Troy, she would have been handed over to the Greeks with or without Paris’ consent; for I cannot believe that either Priam or any other kinsman of his was mad enough to be willing to risk his own and his children’s lives and the safety of the city, simply to let Paris continue to live with Helen. If, moreover, that had been their feeling when the troubles began, surely later on, when the Trojans had suffered heavy losses in every battle they fought, and there was never an engagement (if we may believe the epic poems) in which Priam himself did not lose two of his sons, or three, or even more [. . .] even if Helen had been the wife of Priam the king, he would have given her back to the Greeks, if to do so offered a chance of relief from the suffering which the war had caused (Herodotus, Histories, II.120)

- The woman you call the mother of the child

is not the parent, just a nurse to the seed,

the new-sown seed that grows and swells inside her.

The man is the source of life—the one who mounts.

She, like a stranger for a stranger, keeps

the shoot alive unless god hurts the roots.

I give you proof that all I say is true.

The father can father forth without a mother. (Aeschylus, Eumenides, 665–74) - “Why is light given to one in misery,

and life to the bitter in soul,

who long for death, but it does not come,

and dig for it more than for hidden treasures;

who rejoice exceedingly,

and are glad when they find the grave?

Why is light given to one who cannot see the way,

whom God has fenced in?

For my sighing comes like my bread,

and my groanings are poured out like water.” (Job 3:20-24) - Come to me here from Crete, to this holy

temple, where you have a delightful grove

of apple trees, and altars fragrant

with smoke of incense.

Here cold water babbles through apple

branches, and roses keep the whole place

in shadow, and from the quivering leaves

a trance of slumber falls; (Sappho fr. 2.1-8) - You must say, then, that what gives truth to the things known and the power to know to the knower is the form of the good. And as the cause of knowledge and truth, you must think of it as an object of knowledge. Both knowledge and truth are beautiful things. But if you are to think correctly, you must think of the good as other and more beautiful than they. In the visible realm, light and sight are rightly thought to be sunlike, but wrongly thought to be the sun. So, here it is right to think of knowledge and truth as goodlike, but wrong to think that either of them is the good—for the state of the good is yet more honored. (Plato, Republic, 508d-509a)

- The human good proves to be activity of the soul in accord with virtue. (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics I.7, sec. 15)

- Death is to me today

Like the smell of myrrh,

Like sitting under a sail on a windy day.

Death is to me today

Like a well-trodden path,

Like a man’s coming home from an expedition.

(Dialogue of a Man and His Soul, pp. 159-160)

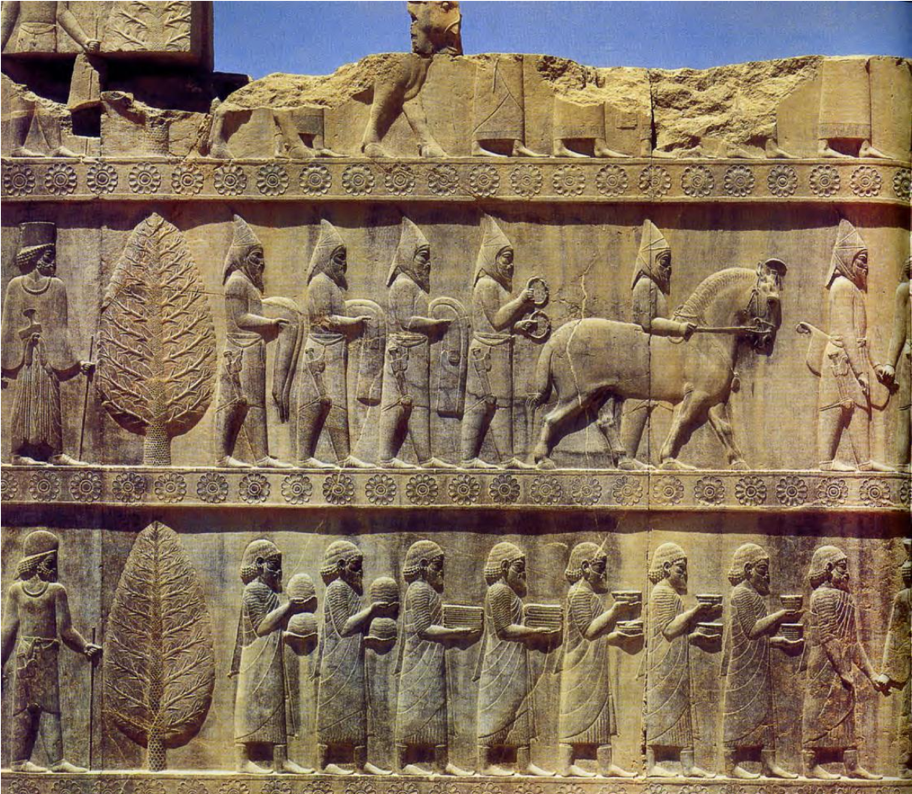

(Persepolis, the Apadana)

Part Two (one and one-half hours): Write an essay on ONE of the following topics:

- In many ancient works the human realm is contrasted with the divine and/or animal realms. Describe how humans are distinguished from gods and/or animals in three texts from this semester, and discuss what this tells us about how those works define what it means to be human. You might consider: Gilgamesh, Genesis, Exodus, Job, the Odyssey, Theogony, the Parthenon, the Republic.

- Throughout the semester we have encountered various texts that question language and its relationship to meaning, truth, history, authority, and belief. Evaluate three texts from this semester and consider how they answer the question: can language be trusted? You might consider: Genesis, Job, the Odyssey, the Bisitun Monument, Thucydides, Medea, the Republic.

Part Three (one and one-half hours): Write an essay on ONE of the following topics:

- Plato and Aristotle both consider the constitution of human beings and come to conclusions about how one should live. Plato argues that knowing the structure of the human soul, you will be able to see why justice in the soul is a good thing and why the life of justice is a good life; Aristotle argues that by looking at the function of a human being, you can tell what happiness and virtue are for a human being. Explain how each philosopher defends his argument. Whose argument is more convincing, and why?

- Book 10 of the Republic describes the terrible fate of a soul who had lived “his previous life under an orderly constitution, where he had participated in virtue through habit and without philosophy.” In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that moral virtue in fact comes about as a result of habit. Does Aristotle really disagree with Plato about the importance of habit and the role of philosophy in attempting to live the good life?