IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 95, No. 1: March 2016

Loosen Up. Festoon.

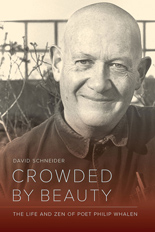

New biography reveals the Zen of Philip Whalen ’51

By John Sheehy ’82

The image of the iconoclastic outsider has cut a deep archetypal vein through the Reed consciousness ever since President William T. Foster, at the ripe old age of 31, set out to upend higher education with the launch of Reed College. Almost nine decades later, Apple Computer’s famous television ad known as “Crazy Ones,” might as well have been a toast from Steve Jobs ’76 to fellow Reedies past, present, and future:

“Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things.”

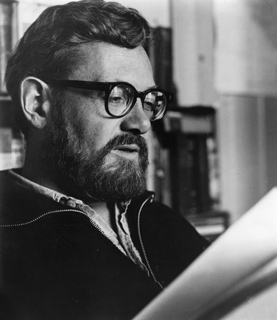

Aside from Jobs, arguably the three brightest stars in Reed’s constellation of cultural disruptors over the past half century have been the trio of Beat Generation poets, Gary Snyder ’51, Lew Welch ’50, and Philip Whalen ’51. While students at Reed in the late forties they formed the literary nucleus of 1414 Lambert Street, the legendary first off-campus student-run house. There, with a shared passion for jazz, Lead Belly, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams, and Asian studies, they fermented a subculture hotbed of intellectual and countercultural bohemianism before setting off to forge their own paths through buttoned-up, conservative, post-war America.

Drawn into the transgressive energy of the San Francisco Renaissance literary scene, the trio became major figures, along with such east coast writers as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, in forging a new social mythology of American freedom, one drawing from Thoreau and Whitman with a sprinkling of Zen Buddhism, that became known as the Beat Movement. What Snyder, Welch, and Whalen contributed to the west coast chapter of the movement were three distinct but compelling writing styles distinguished by subtle intelligence, a love of nature, and a keenly felt spiritual reality.

While Snyder headed off for many years to study Zen in Japan, and Welch began a short-lived career at a Chicago advertising firm, Whalen stayed largely in the Bay Area, where, undaunted by the impoverished career path of a poet, he courageously pursued a life of the mind. As we learn in Crowded by Beauty: The Life and Zen of Poet Philip Whalen, the engaging new biography by David Schneider ’73, the mind at work was in fact the evolving focus of Whalen’s poetry and later study as a Zen monk.

Born in 1923 in Portland, Oregon, Whalen grew up in the small Columbia River town of The Dalles. He attended Reed College on the G.I. Bill, where, under the mentorship of Lloyd Reynolds, professor of creative writing and calligraphy, he determined to become an accomplished writer. Witty and erudite—although prone to grumpiness and temper tantrums—Whalen built much of his life around a relationship to language. A voluminous reader, Whalen had digested a fair amount of the canon of English literature as well as a number of Asian texts of philosophy and literature before finishing college. Like Snyder and Welch, he was strongly influenced by the poet William Carlos Williams, who spent time with the young poets during a visit to Reed in 1950.

Whalen’s discovery of Williams’ poetry opened up for him the possibility of freedom from an “academy” notion of a poem, which he viewed as narration of subject matter bound up in a preconceived ordering sequence. He realized that a level of reordering could take place not only in the line on the page but also in the sound structure of the language itself. Much like Gertrude Stein, another early influence, he began setting up certain dramatic expectations in his poems that he continually challenged and deconstructed. His primary concerns were with the nature of mind and perception, which he displayed in associative leaps from particular details of observation and experience to echoes and ephemera of his distant memory, all conveyed with a comedic ear for puns and bon mots, and punctuated by sensitive attention to the workings of his own alert mind.

The approach is perhaps best expressed by one of Whalen’s own lines from his epic poem, “Scenes of Life at the Capital,” as “Loosen up. Festoon.” And festooning is what Whalen does. Like many of the Beats, there’s a wild energy released in his work. He takes to a poem like a brilliant jazz artist, riffing on almost any relation of form passing through his mind and perception. As literary critic Paul Christensen describes it, “this is Imagism gone to Vaudeville, gag lines thrown in with a rimshot on the punchlines.”

Despite a lifelong aversion self-publicity, Whalen occupies two premier roles as a cultural disruptor in the twentieth century: first, as a poet’s poet of the Beat movement, and second, as a key figure in the early transmission of Zen Buddhism to the West.

In his keenly observed but compassionate biography, Schneider explores in depth both story lines. Dispensing with the tradition cradle-to-grave biographical arc, Schneider structures the first half of the book around Whalen’s relationships with five major characters of the Beat movement: Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, Joanne Kyger, and Michael McClure. Drawing largely from personal journals, letters, and interviews, he steers clear of rehashing oft-told heroic tales of the Beats, instead offering with these set pieces a fresh and humanizing behind-the-scenes view of the Beats’ inner circle as the movement unfolds.

The latter part of Schneider’s biography explores Whalen’s last thirty years spent as a Zen monk, and in particular his relationship with his teacher and patron, Richard Baker. In between, during much of the 1960s, we find Whalen in something of a wandering-in-the-wilderness period, cast about in penury, mooching off friends, teaching English in Japan, picking up one menial job after another as he struggles to devote his time and focus to his craft as a poet.

Indeed, it is during this stretch of homelessness and joblessness that Whalen is at his most productive, generating some of his best work, as reflected by his first major collection of poetry, On Bear’s Head, which was shortlisted for a National Book Award in 1970. Yet we hear relatively little about the poetry itself, nor how it evolves over time, in Schneider’s biography. His interest is more in Whalen’s life experiences, and particularly his spiritual evolution.

Here, Schneider, who moved to the San Francisco Zen Center after dropping out of Reed in 1972—shortly after Whalen himself first moved into the center—is on solid ground. Ordained himself as a Zen priest in 1977, Schneider writes with personal familiarity and authority about Whalen’s initiation as a Zen monk, intimately guiding us through the spiritual transformation he undergoes at Tassajara, the Zen Center’s remote monastery in the mountains east of Big Sur.

As Whalen’s study of the nature of mind shifts from literature to Buddhism, his orientation moves from the philosophical to the experiential. His poetry, which dramatically decreases in both length and output, turns more reflective and quizzical, as he transitions from being a poet with a meditation habit to a monk with a writing habit.

Yet, within the reserved, Japanese-styled mannerisms of the monastery, Whalen remains ever the disruptor, talking theatrically, humming, scat-singing, dancing on tip toes through the silent meditation hall, “fat where most everyone else was trim, loud where everyone else was quiet . . . older, crazier, funnier.”

In other words, still festooning.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago