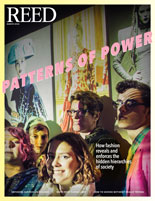

IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 95, No. 1: March 2016

Sculptor of the Surreal, Whacker of Flowerpots

The high-wire life of Xenia Kashevaroff Cage ’35

By John Sheehy ’82

Xenia was photographed by Edward Weston in 1931. This portrait is now in the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Xenia with one of her wood-frame and rice-paper mobiles, circa 1943.

The party began as many others had for Xenia Kashevaroff Cage ’35—with a hint of chance, of wild possibility, in the air. The year was 1943 and the artist and her husband, musician John Cage, were attending a small gathering of writers, actors, musicians, and artists—a number of them refugees from war-torn Europe—at Hale House, the Beekman Place mansion of art collector Peggy Guggenheim. A crossroads for the wartime New York art world, Hale House hosted a steady stream of intellectuals, and Guggenheim’s parties were known for being fast and loose. Tonight was to be no exception.

Xenia and John had arrived in New York City a few months earlier with only 25 cents between them. They spent a nickel at the bus station to call Max Ernst, the surrealist artist they had met at the Chicago School of Design, who was married to Guggenheim. Weeks later, having worn out their welcome, the Cages began couch-surfing around Greenwich Village, camping out for a time with the mythologist Joseph Campbell and his wife, dancer Jean Erdman. Xenia had first met Campbell ten years before while summering at an uncle’s cabin in Sitka, Alaska, after her freshman year at Reed College. Sunning topless on the beach one day, she heard a splash. Suddenly, she wrote, out of the sea “came this heavenly, naked Joseph Campbell, glistening with cold icy water.”

Now, a decade later in New York City, Campbell and the Cages stood on the threshold of fame. Campbell had just published his first book on the hero myths of the Navajo. Xenia and John had catapulted into the national spotlight thanks to their eye-opening performance at the Museum of Modern Art. With John conducting, Xenia and twelve other percussionists beat on 125 instruments, ranging from hand drums to snare drums, brake drums, Chinese gongs, cymbals, woodblocks, cowbells, a thundersheet, a washtub, tom-toms, and bongos. The group had previously toured colleges in the Pacific Northwest, including Reed, where student critic and future Portland conductor Jacob Avshalomov ’43 panned their performance in the Quest as “better heard than seen.” Time magazine was somewhat more generous in covering their wacky New York appearance:

“Percussionist Cage, 30, is firmly convinced that percussive noise poems will bulk large in the musical future. . . . His steadfast fellow percussionist is his blonde wife Xenia Cage, surrealist sculptress, daughter of a Russian Orthodox priest. She helps Cage find his instruments of ‘unsuspected beauty’ in junkyards and hardware stores. He considers her the deftest of all living flowerpot and gong whackers.”

The youngest of six talented, striking, and volatile sisters, Xenia was born in Juneau, Alaska. Her father, Andrew Petrovich Kashevaroff, was the archpriest of the Russian Orthodox Church of Alaska. His father, a Russian sea captain, had married a native Alaskan, making Xenia one-quarter Alutiiq, or Sugpiaq. During high school she went to live with two older sisters in Carmel, California, falling in with their free-spirited social circle that included writer John Steinbeck, photographer Edward Weston, and pioneer ecologist Ed Ricketts—the model for the character “Doc” in John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row. Xenia became sexually involved with Ricketts (who was married) while she was still in high school. She also formed a liaison with Weston, who introduced her to sexual trios, while she was a student at Reed. Weston’s iconic portraits of Xenia, including a number of nudes, hang today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Courting unorthodoxy came naturally to Xenia, who relished chance and experimentation both in her life and in her work as an avant-garde painter and sculptor. That was evident from her first encounter with Cage in 1934, when she walked into the arts and crafts shop in Los Angeles where he was working. She had recently moved to the city after dropping out of Reed to continue her studies at the nearby Chouinard Art Institute. John had just returned from a grand tour of Europe after having dropped out of Pomona College. He was immediately drawn to Xenia’s exotic complexity and “barby” wit, and asked her out to dinner. That same evening he proposed marriage. A year later they were wed at dawn in the Arizona desert.

The atmosphere of intrigue mounted as the guests arrived: artist Marcel Duchamp, writer William Saroyan, and striptease artist Gypsy Rose Lee. When Guggenheim suggested that Lee use some of John’s music in her act, Lee, who had been stripping for nine years to the pop song “Frankie and Johnny,” said that she wasn’t interested in changing something tried and true.

Not so Xenia. After Lee and most of the other guests departed, she decided to don a costume. Raiding Guggenheim’s closet, she found a pair of chartreuse-and-purple lounging pajamas, cut low in the back. When she re-emerged at the party, Duchamp and Max Ernst teased her that she had the outfit on backward. Accepting their dare, she reversed the pajama top, turning the revealing low-cut back around to the front. What followed was a group dash to the bedroom.

The legendary madcap evening exemplified Xenia’s adventurous spirit. It also illustrated the thrills, but not the dangers, of living life as a high-wire act. Within a year of the party, Xenia would lose John to the dancer Merce Cunningham in an affair that began as a friendly ménage a trois. Cage and Cunningham would go on to great fame as artistic and romantic partners in the postwar avant-garde.

Xenia, meanwhile, began gaining notice in New York as a painter and sculptor in her own right. Artist Penelope Rosemont describes her as being on the “cutting edge of surrealism in sculpture.” Her elegant, fragile mobiles of balsa wood and rice paper were featured in Exhibition by 31 Women at the Guggenheim Museum, in a one-woman show at New York’s prestigious Julien Levy Gallery, and in exhibits alongside artists such as Dorothea Tanning, Marcel Duchamp, Kay Sage, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Isamu Noguchi, and Robert Motherwell. Bookbinding, an art she learned from the legendary Hazel Dreis, not only helped pay the bills but also led to collaborations with Duchamp on his Boîte-en-valise and Ernst in designing a modernist table bench for his famous chess set. She designed costumes for Erdman and acted in experimental films by the director Maya Deren.

By the fifties however, Xenia disappeared from public view, along with her art. She supported herself by working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum, and, beginning in 1968, as a longtime cataloguer and conservator at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. When she died in 1995 at age 82, she was not a forgotten artist, but tragically, an unknown one. Virtually none of her artwork has survived. Her ashes were carried back to the family plot in Juneau. Jean Erdman, her fellow flowerpot and gong whacker, paid for her funeral.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago