IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 91, No. 2: June 2012

President Diver: The Exit Interview

After 10 years at the helm, Colin Diver takes stock.

By Chris Lydgate ’90

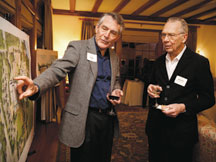

Diver shows plans for performing arts building to Darrell Brownawell ’54. Describes mutant sturgeon he “nearly” caught in canyon. Rides in buggy as Simeon Reed with Joan as Amanda at Reunions 2011.

When Colin Diver arrived at Reed in October 2002, Saddam Hussein still ruled Iraq, Google was not yet a verb, and no one had heard of toxic assets.

As Diver moved into the president’s office on the third floor of Eliot Hall, he could not have predicted the extraordinary events that would change the world over the next decade, from the Arab Spring to the advent of the iPhone.

The changes at Reed have been less tumultuous, but no less significant (see “The Diver Decade”). Nonetheless, with the premise of a liberal arts education coming under fire in an era preoccupied with vocational training, Diver insisted that Reed stay true to its mission: intellectual passion, academic rigor, and creative ferment.

Diver has been an active and engaged president, serving as thesis adviser, teaching a class in constitutional law, eating in commons, and even riding in a horse and buggy disguised as Simeon Reed, with his wife, Joan, as Amanda. The thesis parade now regularly wends its way through his office, where he receives sweaty hugs from delirious seniors as they celebrate turning in their theses. Indeed, Diver has remained remarkably popular with students, who have bestowed upon him the nickname “C-Divvy.”

Diver has also demonstrated a knack for a certain kind of offbeat pageantry. Garbed in a ceremonial gown of unrelenting fuchsia, he has regaled audiences with memorable one-liners. At Convocation 2009, for example, he proclaimed “the creed that generations of Reed students have embraced: Capitalism, Faith, and Sexual Abstinence . . . or something like that.” Celebrating Reed’s centennial in September 2011, he led a chorus of thousands in chanting the first line of the Iliad.

In the final months of his reign, we caught up with Diver to take stock and contemplate the challenges ahead. This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

What’s your proudest achievement?

Far and away the most important is the improvements we’ve made to students’ health and well-being. The most obvious statistic is the improvement in the graduation rate. That’s hugely important. I’m very proud of that, although I’m not sure how much credit I deserve for it. I believe that the old approach of “trial by fire” is not sustainable—that’s a controversial belief, by the way. When I got here, some people were proud of the fact that Reed was about the survival of the fittest.

Lurking behind that statistic [improved graduation rate] are a whole bunch of things. We beefed up academic support—things like the DoJo, the sports center, the health and counseling center. The utilization rates of these resources are just off the charts, and I believe that’s a great thing.

How would you respond to people who say Reed should focus on “the life of the mind” and let students figure out the other stuff on their own?

Even if I accepted that proposition—which I don’t—the mind is connected to a body and is profoundly influenced by physical life, emotional life, and I would add, spiritual life. It is a scientifically demonstrated fact that 17–22-year-olds are still maturing. They may reach their cognitive peak early, but their emotional development takes much longer. Reed is a residential community, and our philosophy of education is highly interactive. Students are not like monks in a cloister copying scrolls. We treat them as scholars in a community of scholars. Part of our job is to help them make the transition from dependence to independence.

You’ve been a big advocate of the performing arts. Why?

I believe that the fully educated person needs to be capable of creative work, inquiry, exploration, teamwork, and to be able to turn their knowledge into some kind of product—an essay, an experiment, an artistic creation, or a performance. These are all key elements of the performing arts, and when I got here I thought that those disciplines were some of the least well supported academically.

I wouldn’t have expected that from a lawyer. Have you ever been onstage as a performer?

I used to sing in a choral ensemble and do a little cameo acting. But you know, if you’re a college president, or even a law school professor, you are a performer. It’s part of your job. My dad was a technical photographer and loved classical music. He used to take me to shows when I was growing up. When I was in law school, I can remember seeing Verdi’s Don Carlo at the Met. It was just electrifying. I also saw Pavarotti perform before he became a household name. I’ve always enjoyed carpentry, fixing up old houses. I’ve always felt that creating things was a central part of my life.

I also felt that every college that aspires to be a genuine community has got to provide collective endeavors that create a school spirit. We don’t have fraternities or sororities. We don’t have varsity athletics. So the performing arts have a special role to play at Reed.

What about Renn Fayre?

I feel that Renn Fayre has become distorted from its original purpose. If we can return Renn Fayre to its roots as a true community-wide celebration, and channel it in the right direction, I think it can serve a valuable function. But on this campus, you can’t just wave a wand and decree things, no matter how much you might want to.

OK, if you had a magic wand . . .

The most obvious example is addressing illegal drug and alcohol use. It’s emphatically a legal obligation. I think it’s a moral one, too. I came to Reed knowing this was a community that had a lot of expectations about student autonomy, self-reliance, and an ingrained suspicion of authority. I’ve discovered that there is actually a very powerful authority on campus—the faculty—but only in their academic role. That’s part of the social contract here. Students accept that they are academic apprentices to the faculty. But that’s the extent of it. The faculty retain their authority because they guard it very carefully. The rest of us do not have a lot of intrinsic authority. We have to earn it. That’s a challenge, but it’s a good challenge to have. You need to be able to say to yourself, do I have a good reason for my beliefs and actions and does it resonate with Reed’s mission? And, if you don’t have a good answer, it’s probably time to take a step back.

What about the endowment?

We have built a first-rate development operation. It’s a powerful and professional group. To have raised $199 million in the worst economic downturn since the great depression is just remarkable. And the good news for the future is that three-quarters of what we have raised has gone straight into the endowment. As for management of the endowment, for 30 years Reed benefited from the investment genius of our alumnus and board member Walter Mintz ’50. After he died early in my tenure, we went through a difficult transition, but I am happy that our investment returns have been getting steadily better.

You have overseen a lot of physical expansion.

I’m proud of the dorms we’ve built. We’re not quite at our goal of having enough space for 75% of our students to live on campus, but we’re close. Dorms—good dorms, at least—are expensive. We are building a first-class performing arts building. We also expanded the campus footprint. We bought the old hospital and the farm. That will give us a little more breathing room.

Is Reed diverse enough?

Diversity is still a work in progress. We made a lot of progress in admission, and we have not used merit aid. But we still struggle to attract African American students. Maybe it’s my earlier involvement with civil rights issues in Boston, but I still think that the biggest piece of unfinished business in America is the position of African Americans in our society. We need to do better. I am also frustrated at the slow progress of hiring faculty of color. We have a genuine institutional commitment to diversity. That’s great. We’ve made the cake. Now we have to bake it.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago