IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 92, No. 4: December 2013

Theatre of War

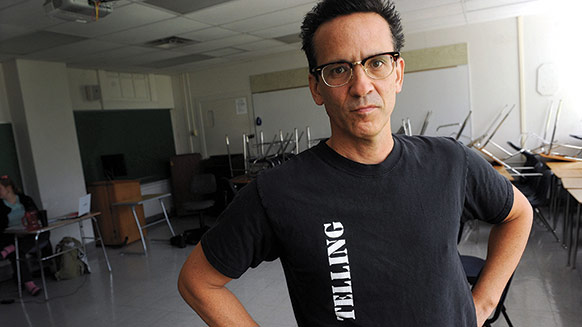

Jonathan Wei at a rehearsal for “Telling: Austin” Photo by John Anderson

Jonathan Wei ’88 helps military veterans tell their stories.

By Robyn Ross

As an army officer, Lieutenant Colonel Steve Metze wasn’t supposed to show emotion in front of other service members. He definitely wasn’t supposed to cry.

But standing on stage in his final performance in “Telling: Austin,” Metze broke the code. He delivered his closing lines—about his belief that everyone should serve in the military—then paused. A sense of impending loss, a feeling he’d kept at bay throughout the performance, overcame him. He’d spent months preparing for the show with his 12 fellow cast and crew members. This was the last night they would be together.

More importantly, in his 24-year military career, these were the first people he’d talked to about his experiences. Even his wife hadn’t heard these stories.

So Metze went off script—totally off script—and began to tell each member of the troupe what he admired most about them. “None of it was planned,” he said later. “There were tears for most of the people there. But I was glad I said those things, because those other seven people and those five crew members were the only people I’d ever really talked to about those things, and the only people I felt really wanted to listen.”

Metze’s catharsis was a surprise to his fellow performers, but less so to Jonathan Wei ’88. For the past six years, Wei has staged the Telling Project in 15 cities, including Portland, Baltimore, and Des Moines. The project is a theatrical performance drawn from the real stories of local veterans and their families. It’s presented to a local audience with the intention of closing the gap between those with and without military experience.

“People in the show will talk about things they don’t talk about otherwise,” Wei says. “I’ve seen spontaneous stories told during the show that people have never told, but on stage, in that sacred space, they can do it. The format and ritual of theatre allows people to speak, and audiences to listen.”

They do more than listen. The response to Telling has been overwhelming. Audiences laugh, weep, and give standing ovations. Critics write about feeling simultaneously enlightened by and grateful for the performance. “The stories are raw and funny and moving,” the Washington Post’s Michael Rosenwald said of a 2012 Baltimore performance. “Go see this play.”

“This is a brave, powerful undertaking,” wrote Diana Nollen in the Cedar Rapids Gazette about a Telling performance in Iowa City. “If I hadn’t been so busy writing, observing and evaluating, I would have been crying, like so many others around me.”

The project has been supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and the Smithsonian Institution. It’s been featured on NPR, Fox News, and CNN. Both Michelle Obama and Jill Biden have seen it.

The acclaim is even more impressive when you consider that the performers are not actors, but veterans—most of whom have never been onstage before.

![]()

Telling was born in Eugene, where Wei was working as a student adviser at the University of Oregon while his wife was in graduate school. One of his responsibilities was advising a veterans’ student organization that held outreach events but wasn’t attracting its intended audience: people with strong opinions about the military and war but with little exposure to either.

A writer by trade, Wei woke up one morning with an epiphany: he’d write a play that would allow veterans to tell their stories onstage. Working with a cowriter, a director, and performers from the student group, he created a play that was performed nine months later in Eugene.

In each Telling city, Wei works with local veterans’ organizations to recruit participants and then gathers their stories via interviews usually lasting between 2 and 4 hours (the longest went for 12). He then invites anyone who’s interviewed to perform. Local cowriters help him shape excerpts from the interviews into a script, and a local director coaches the cast in basic performance technique to help everyone feel more comfortable onstage.

Steve Metze graduated from West Point in 1989. A lieutenant colonel in the Texas Army National Guard, he served in the Gulf War, Bosnia, and Iraq, and now works as a manager in the semiconductor industry in Austin. Unlike most of the cast, he had a bit of performance experience from a season doing improv at a Renaissance festival. This background is most evident when it combines with Metze’s dry sense of humor in act one, relating to the cast’s misadventures before and during basic training.

“You’ve got me trying to get in shape by running around in dress shoes,” he says, explaining that he trained by jogging around his hometown in shorts and black oxfords. He’d seen a photo of West Point cadets in a similar ensemble and thought that’s what was worn for physical training. “You’ve got me continuing to look at the cadet who was yelling at me not to look at him; me demonstrating ways to screw up at the dinner table at West Point.”

But in act two, the tone shifts. The cast goes into details about their deployments and the more difficult situations they faced. Metze speaks about the stress his deployments put on his relationships and about moments of violence in Iraq. One haunting image was the ring finger of an Iraqi insurgent who had blown himself up in Tikrit. When Metze investigated the scene, he saw the dead man’s finger lying in an unnatural—and unforgettable—way, bent back against his hand.

In act three, Metze talks about his experiences coming back home. How he had recurrent nightmares about being attacked by zombies (apparently not uncommon among combat veterans). And about one nightmare in particular where “the lead zombie in front only had one arm—and it was that guy.”

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago