IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 91, No. 4: December 2012

The Books Issue

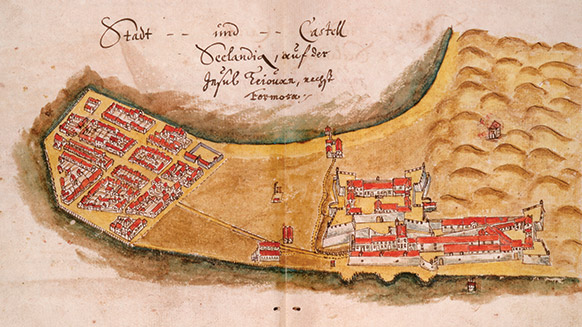

How the Dutch Lost Taiwan

Sketch of Zeelandia Fortress (to the right) from 1652 clearly shows angled bastions protruding from castle walls. These bastions eliminated “dead spaces” and allowed Dutch defenders to repel Koxinga’s forces—until the Chinese general figured out how to neutralize this technological advantage.

Tonio Andrade ’92 examines China’s first great military victory over the West.

By Miles Bryan ’13

Tonio Andrade ’92.

Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West

Princeton University Press, 2011

Dutch general Thomas Pedel was brimming with confidence as he led his troops out of Zeelandia Castle on Taiwan to battle the Chinese warlord Koxinga in the spring of 1661. The Dutch had been fending off attacks by Taiwanese natives and Chinese settlers since they established a colony on the coast of Taiwan a few decades before. These raids posed no serious threat: Dutch muskets were the best in the world, while Chinese arrows and cannons seemed like a relic from Europe’s Middle Ages. Although Pedel’s son had been maimed by Koxinga’s troops earlier in the day, Pedel was certain his 250 crack sharpshooters would be more than enough to dispatch Koxinga’s force of a few thousand. He was wrong.

Just 80 Dutch musketeers limped back to their castle after the skirmish, a crushing defeat for the Europeans. Yet this loss was not decisive: it took another year before the Dutch colony surrendered to Koxinga’s fearsome army.

The Sino-Dutch war for Taiwan raises some tantalizing questions: how did the Chinese defeat the Dutch, with their superior military technology and organization? Conversely, how did a few hundred Dutch manage to hold out against Koxinga’s huge army for as long as they did? These puzzles are what historian Tonio Andrade seeks to explore in Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West.

Tonio concludes that a host of ecological, technological, and personal factors contributed to Koxinga’s dramatic victory. In taking such a multifaceted approach he breaks with the binaries—orthodox or revisionist, Eurocentric or Asiacentric—traditionally used by historians to understand early modern European-Asian interaction. Such an eclectic approach is nothing new to Tonio, who has been defying tradition since he was inspired by seeing the Reed documentary, A Different Drummer, on one of his first days on campus.

In his first two years at Reed, Tonio’s quest for truth played out in the halls of the biology building. He wanted to be a biologist or neurophysiologist, but had a change of heart when he had to kill and dissect a rat. He took a year and a half off to reorient himself, spending time in his hometown of Salt Lake City and in Taiwan, where he studied Chinese language and history.

Although he eventually graduated from Reed as an anthropology major, Tonio was most inspired by the intellectual history classes of Malachi Hacohen [history 1989–93], now tenured at Duke. In Hacohen’s class on the German impact on French culture, Tonio learned to look for cross-pollination, the connections that form the deep roots of history. He was drawn back to the ivory tower soon after his thesis was bound, earning master’s degrees at the University of Illinois and a PhD from Yale. He taught history at SUNY and then at Emory University, where he has been ever since.

Tonio’s curiosity is reflected in his self-description as a world historian and is manifest in Lost Colony. With a scientist’s attention to detail, he shows how the Dutch withstood Chinese attacks for so long because of two factors: their warships and their fortresses.

Dutch ships were larger and heavier and carried more cannons than Chinese junks, which gave them the upper hand in open water and clear conditions. Fortunately for the Chinese, these conditions were rare. The Dutch ships often struggled in the violent monsoons and shallow waters of Taiwan, while Koxinga’s junks used their superior speed and familiarity with the coastline to launch surprise attacks. In this war, however, agility mattered more than firepower. The sophisticated rigging and multiple sails of Dutch ships allowed them to sail against the wind—a crucial advantage over the single-sailed Chinese junks.

The second, and most important, Dutch advantage lay in the design of their fortresses. The Renaissance fortress developed in Italy in the 15th century, when the increasing number and firepower of cannons used in a siege began to overwhelm traditional castles. In response, nervous lords developed a new kind of fort; their key innovation was an angled bastion thrusting out from each corner and at intervals along the fort’s walls. These bastions allowed defenders to keep the entirety of the fort’s walls in their line of fire, thus eliminating the dead spaces—areas along the fort’s walls that are difficult or impossible to cover—that besieging armies traditionally focused on climbing up or blowing apart. This in turn led to an arms race of bigger and better siege technology. Attacking a fort in Europe became a prolonged and elaborate affair of siegeworks and counter siegeworks.

Chinese fortresses evolved differently. While they dwarfed their European counterparts, their design was simple: thick, flat walls set at right angles. Some of these forts did have fortified outposts extending from the walls, but these provided only limited cover. Koxinga had overwhelmed many of these forts in his battles on mainland China simply by rushing them with his huge and well-trained army. He was dismayed when his first attempt to storm Zeelandia Castle resulted in miserable defeat.

After his first rush resulted in catastrophe, Koxinga set up cannons behind a hill and tried to shell the fort into submission. The Dutch built a new fortification to provide counterfire, but Koxinga knew he was onto something with his primitive siegeworks. Next, he constructed a coastal fort, with elements of Renaissance design, to try and cut Zeelandia off from seaborne provisions. The Dutch once again built a counter-fortification and staved off the threat.

Koxinga finally captured Zeelandia thanks to crucial intelligence, courtesy of a hard-drinking European turncoat named Hans Radis, who told Koxinga that he needed a more elaborate set of siegeworks to win—and Koxinga listened.

For Tonio, Koxinga serves as something of a parable for why the Chinese were ultimately able to defeat the Dutch on Taiwan. Koxinga overcame Dutch technological advantages because he was creative and adaptive. He gained in a year a rudimentary understanding of the Renaissance technology that Europeans had taken centuries to develop. Dutch leadership does not stand up so well to historical scrutiny. Fredrick Coyet, Koxinga’s counterpart, was haughty and inflexible: his quarrels with top officers and regional generals resulted in crucial losses of supplies and support, and his quickness to put lower-ranked men in their place made a tense situation (they were cooped up in the castle for months) often unbearable. Pedel and his musketeers lost the battle because he was too arrogant to heed warning signs that the Chinese, led by the seasoned general Chen Ze, were encircling them in a pincer attack.

These findings led Tonio to conclude that although technology, the environment, and chance all played important roles in the Dutch-Sino war, in the end the most decisive factor was the human one. Writing a history that makes human decisions paramount is unorthodox and risky. But sometimes you just have to march to the beat of a different drummer.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago