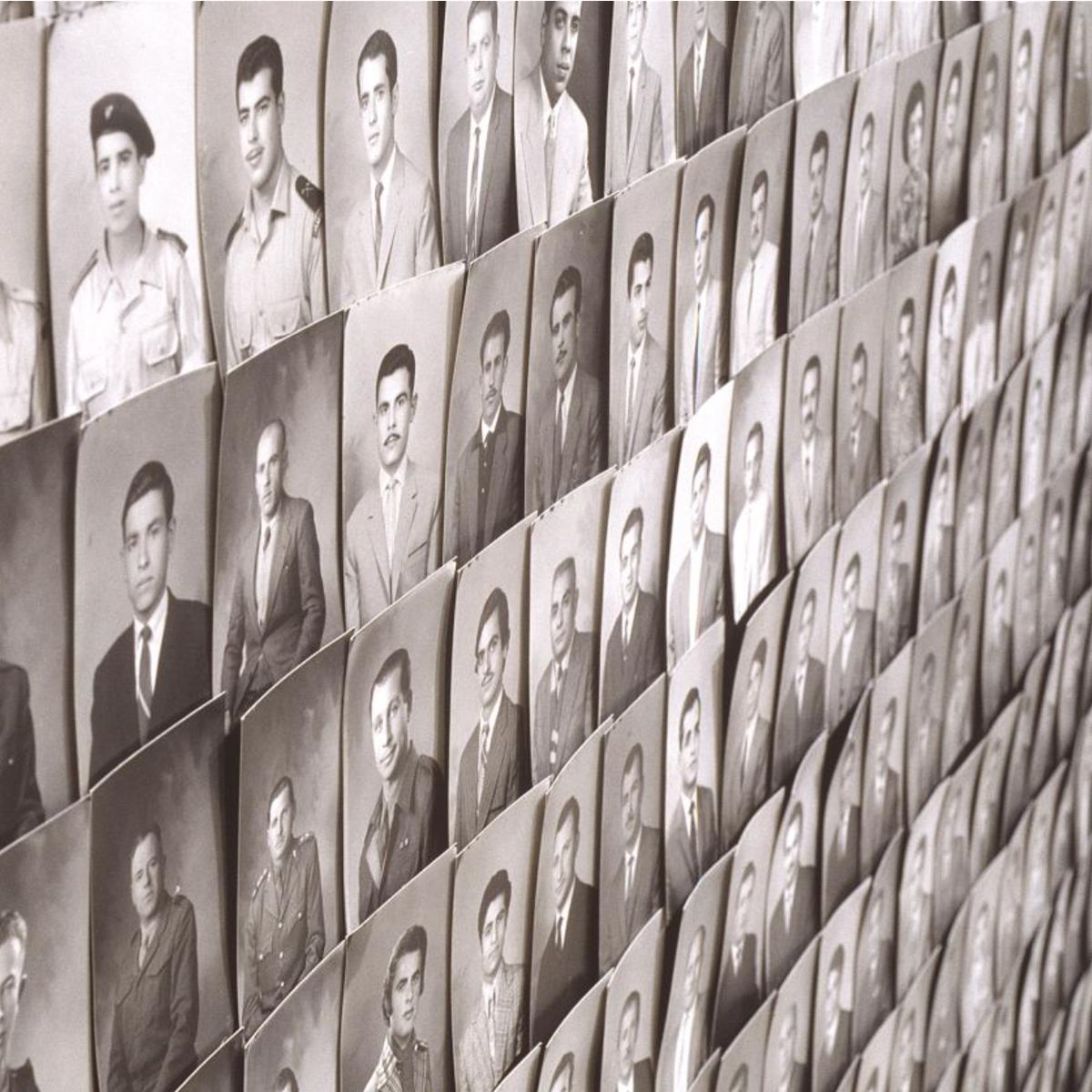

Walid Ra’ad and Akram Zaatari, Installation of ID photos from Studio Anouchian, 2005. Photographic installation: approximately 3,500 photo passport contact prints (3.38 x 2.5 in. each) dating from 1935–70; Tripoli, Lebanon. Archival photos by Antranik Anouchian.

Mapping Sitting: On Portraiture and Photography

Image GalleryAugust 22 - September 30, 2005

In Mapping Sitting, two contemporary artists present installations that dynamically disclose how photographic portraits operated in the Middle East over the last century. On view at the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery from August 22 through September 30, 2005, this timely and topical exhibition was conceived by Walid Raad—a media artist based in New York and Beirut and best known for his innovative project titled The Atlas Group—and Akram Zaatari, a prominent video artist, filmmaker, and curator who lives and works in Beirut. Raad and Zaatari have devised four sections based on the Middle Eastern tradition of "surprise" street photography, on itinerant photography, on institutional group portraits, and on passport images. The latter features over 4,500p postage stamp-sized passport portraits, while a video projection presents group photos of military soldiers taken in Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Egypt in the first half of the 20th century.Raad and Zaatari reveal how Arab portrait photography not only pictured individuals and groups, but also functioned as commodity, luxury item, and adornment. Their installations feature diverse photographs from the Arab Image Foundation—an archive in Beirut housing more than 70,000 images taken by professional and amateur photographers from the late 19th century to the present. Collectively, the photographs convey pluralistic and dynamic Middle Eastern communities through the lenses of indigenous photographers—images far different from photos of the region circulating widely today in the popular press.

Mapping Sitting presents four distinct practices: studio passport photography; institutional group portrait photography; the street tradition of "photo-surprise"; and portraits by itinerant photographers. These four forms are examined through the works of Tripoli-based Armenian photographer Antranik Anouchian (1908–1991); Lebanese photographer Hashem el Madani (born 1930); various group portrait photographers who were active in Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq between 1880 and 1960; and early 1950s street "photo-surprise" images by Setrak Albarian and Sarkis Restikian of the Photo Jack Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon. Addressing the proliferation of photographic portrait industries in the Arab world, the exhibition not only raises questions about portrait photography in the Middle East, but also about portraiture, photography, and visual culture in general.

The history of photography in the Arab world is not well-documented. Introduced in the Middle East by colonial occupiers in the mid-19th century, photography was, at first, dominated by Western practitioners who focused primarily on antiquities, regional landscape, and exotic traditions. Local photographic production flourished after Yessai Garabedian, the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem, held the first photography workshop in the region in the 1860s. In the years that followed, photographic production continued to expand, especially as Armenian exiles, many of whom had been trained as photographers, fled Turkey for Islamic countries. With the arrival of Kodak box cameras in the 1880s and 1890s, the appetite for photographic images increased.

As photography spread throughout Middle Eastern cultures, modernization was transforming the region. The social, political, and economic lives of the emerging nation-states gave rise to nationalist liberation movements along with evolving awareness of geography and identity. Modern building methods and urban planning were implemented, labor and women's movements developed, and new literary and artistic forms focused on identity as the central issue in developing socio-political realities. Contrary to western images of the Arab world, which often depicted marginalized or dehumanized subjects, photographs by indigenous Middle Eastern photographers captured the quotidian lives of these changing communities. Concentrating on commercial photography, Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari—artists who also function in this instance as curators—pose a number of questions: What historical, aesthetic, philosophical, and cultural conceptions of photography are repeated and/or questioned in these images? What can we learn about notions of identity from these portraits? Keeping in mind the peculiar conditions of production, distribution, and consumption of the images, Mapping Sitting also investigates how these photographic practices reveal characteristics of nascent national identities.

Walid Raad is Assistant Professor of Art at Cooper Union in New York City. His works include textual analysis, video, and photography projects. He has recently performed at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; the House of World Cultures, Berlin; and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. In 2002, his Atlas Group was included in the Whitney Biennial, New York, and Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany.

Akram Zaatari is the author of more than 30 videos, including This Day (2003), How I Love You (2001), Her + Him Van Leo (2001). His writings appear in critical and scholarly journals such as Parachute, Framework, Bomb, AI-Adaab, and Al-Nahar. Zaatari is a co-founder of the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut; Raad sits on the organization's board.

Mapping Sitting is complemented by a 250-page publication that includes 840 photographs, designed by Mind The Gap Productions in Lebanon, and co-edited by Karl Bassil, Zeina Maasri, and Akram Zaatari in collaboration with Walid Raad.

Mapping Sitting was organized by the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) and is circulated in the U.S. by the Grey Art Gallery, New York University, and the AIF. The exhibition is made possible in part by the Islamic World Arts Initiative, a program of Arts International generously supported by the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art and administered by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. Additional support was provided by the New York State Council on the Arts.