IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 92, No. 3: September 2013

Coloring Outside the Lines

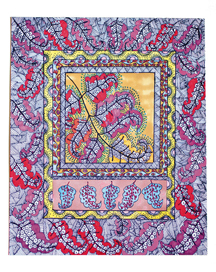

“Some say my artwork is triumphing over my disability, but my disability has been helpful to me,” says Kathleen Flannigan ’62. “Instead of fighting it, I exploit it.” Photo by Ariel Zambelich

Kathleen Flannigan ’62 rallies the disabled artists’ movement.

By Mary Emily O’Hara ’12

Her Berkeley apartment features many of the trappings you might expect to find in an artist’s studio. A worktable covered with sheets of paper, jars of pencils, and markers. Walls festooned with colorful drawings. Hand-painted furniture. A leather case bulging with illustrations—she works mostly in colored pencil on paper, although she also paints a bit and creates mosaics from ceramic tile. Then you notice the steel-armed adjustable hospital bed.

Kathleen Flannigan is not your typical artist.

At 72, the arthritis stemming from her lifelong cerebral palsy now requires Kathleen to use a wheelchair. But she says that living with disability is part of what brings her art to life.

“Some say my artwork is triumphing over my disability, but my disability has been helpful to me—instead of fighting it, I exploit it,” she says. “My work is unique because I am unique.”

Kathleen’s work has been shown at the Smithsonian and in locations as diverse as Brussels and Rio de Janeiro. She is an artist in residence at the California Academy of Sciences, and her work was recently shown at the exhibition Parallel Universes: The Flowering Gardens of Downtown Berkeley in the San Francisco Library. She has won numerous prestigious awards, including a Pollock-Krasner grant. On top of all that, she holds down a part-time job at Disability Rights California, a law firm where she acts as a consultant and liaison to the disabled community.

Kathleen’s hands tend to curl up as she speaks. Cerebral palsy, a neurological condition that can affect movement as well as the senses, first appeared when she was a girl. “I had a strange gait,” she recalls, “and my mother wanted a perfect child, so I had all these operations.”

Cerebral palsy affects each person differently. Fortunately, it did not impair her coordination—or her intellect. She was an excellent student who attended Catholic high school before coming to Reed, where she flouted convention to live with three male students in a beatnik group house on Southeast Long Street. “It was a very primitive place; there was no heat. We’d sleep in the attic on sleeping bags. We wore Levi’s and cowboy boots, Navy watch-caps, black turtlenecks.” The arrangement at Long Street House gave her a wild reputation: “It was unusual to live with men,” she says. “I had these freshman boys following me around hoping I would devirginize them!”

At Reed, she met her future husband, Richard Morgan ’60. They got married on campus, and were given the Doyle Owl as a wedding present. (They had to hide it.)

Kathleen left school early and followed her new husband to his sociology graduate program at UC Berkeley. But dropping out to become a housewife turned out not to be a good fit for the independent, spirited young artist. In 1981, she went back to school at the California College of the Arts.

“In art school I was told, ‘Never draw your disability because it won’t sell,’” she says. At that time, she remembers, photorealism was being pushed in art schools, frustrating her desire to create art based on her own vision. “I’m not a Western artist,” she says, “I’m inspired more by folk art, Latino art, outsider art.”

She left school in 1983, ditching the stringent and methodical rules of realism to join forces with a nonprofit arts center, Creative Growth. The Oakland studio and gallery serves adult artists with developmental, mental, and physical disabilities, and provided her with an alternative to the confining fads of the mainstream contemporary art world. Today, many Creative Growth artists—such as textile sculptor Judith Scott, neo-Victorian illustrator Aurie Ramirez, and painter Dwight Macintosh—have entered a crossover zone where outsider art meets the “white cube” of mainstream art.

Kathleen has enjoyed commercial success—she recently sold work to Kaiser for display in their pediatric hospitals, she’s building a business called Blazing Glazings that markets her mosaics and greeting cards, and she’s worked on commissions for corporate clients such as Verizon and 1-800-Flowers. But her most lasting achievements lie on the margins of the art world.

![]()

The Ed Roberts Campus is a sprawling resource center located in Berkeley for people with disabilities. As I crane my neck in the lobby, a man in a wheelchair whizzes past, zooming up a bright red spiral ramp. At its zenith stands an innocuous door marked Community Access Studio.

Inside lies a sunny room, illuminated by floor-to-ceiling windows. Every surface is covered in papers, pens, paints, and markers, while the artists group together laughing and talking. The room buzzes with energy. A young woman comes up to touch my hair and says, “Your hair is pretty.” She asks for a hug. Right away it’s clear why Kathleen loves this place: “I get so tired of all this veneer and appropriateness. These people are not domesticated and overcivilized; they have all this energy.

“Maybe I’m thirsty for love or something,” she says with a smile, “but I love these people and they love me.”

Kathleen doesn’t just appreciate her fellow disabled artists on a personal level; she is an activist who has tirelessly promoted artists with disabilities over the years, acting as an intermediary between them and the commercial art world. She founded the Artists with Disabilities Empowerment Project to show that people with disabilities could do the same good work as able-bodied artists. “They told us it couldn’t be done—but we did it,” she says with a mischievous twinkle and an irrepressible grin.

It’s impossible to spend time with Kathleen without admiring her energy and independence. She speaks her mind. She follows her dreams. Wheelchair or not, she can’t stop moving.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago