IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 96, No. 1: March 2017

Last Lecture: Saluting our retiring (and not-so-retiring) professors

Chasing Coyote

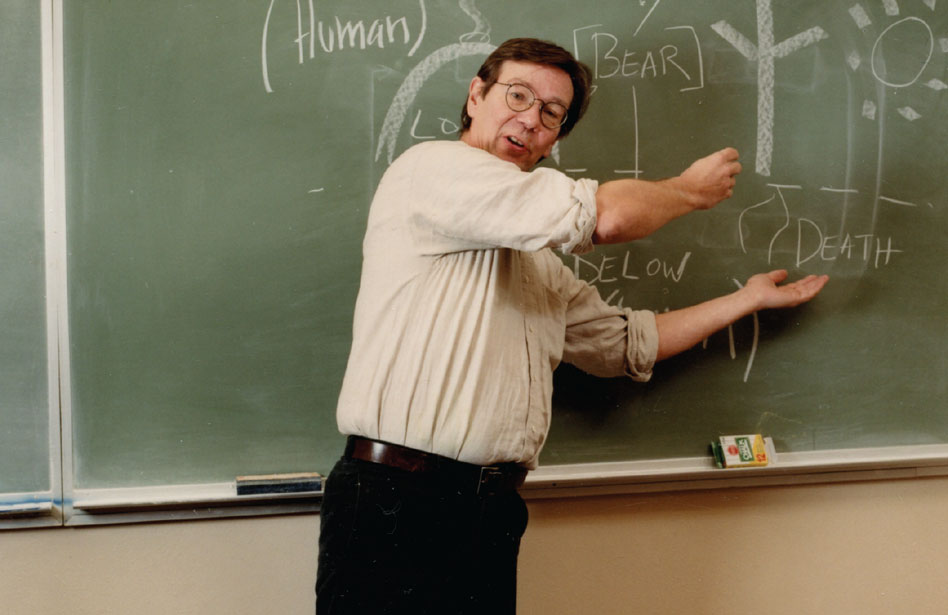

Prof. Robert Brightman ’73 [anthro 1988-2016]

By Randall S. Barton

Though it is impossible to reduce a life’s work to a single element, Prof. Robert Brightman always encouraged his students to “attend to the living, breathing, enculturated, biographical human subjects who inhabit these rhizomic assemblages, hybrid collectives, relational ontologies, post-human Anthropocenes, and other constructs we traffic in.”

He retired from Reed last year, but continues his research in anthropology and linguistics. He also writes short stories and works as expert witness and researcher for legal firms representing Native American communities in Canada and the United States. His 1993 book Grateful Prey examines different aspects of human-animal relations in the hunting practices of the Rock Cree people in northern Canada. He has written comparative studies of hunter-gatherer peoples, focusing on gender and on effects of religious conceptions on sustainable and non-sustainable foraging practices.

Prof. Brightman first came to Reed in the Sixties, as a student planning to major in English. While studying Native American languages and societies with Prof. David French ’39 [anthro 1947-88], he discovered that anthropology fired his imagination. He invokes Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, who suggested that anthropology is a means to the “permanent decolonization of thought.”

Brightman collaborated with French on his senior thesis, The Continuing Adventures of Raven and Coyote: A Comparative Analysis of North American Indian Transformer Myths. As was French’s custom, thesis conferences often occurred in the early a.m. at the professor’s home across the street on Woodstock Boulevard. When Brightman became a professor, he based his own thesis advising on French’s informal and collaborative model, albeit without the nocturnal office hours. The thesis focused on the Native Northwest literary characters Raven and Coyote, and in particular on how their actions institute and explain natural phenomena and cultural practices. In later graduate research with Cree, Brightman encountered similar characters and became interested in the seemingly incongruous juxtaposition of wisdom and benevolence with imbecility and moral chaos in the same personage. For example, the character who institutes the incest taboo in one story, violates it in another.

After earning his PhD from the University of Chicago, he began teaching at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. In 1988, he returned to Reed, where he divided his teaching and research between cultural anthropology and linguistics. In 1998, he was named to the endowed chair in American Indian Studies established at Reed by Ruth Cooperman Greenberg. The many courses he taught included “North American Indians,” “Semiotics and Structuralism,” “Algonquian” (linguistics), “Myth and Folktale,” “Subject, Person, Self, Individual,” and “Nature, Culture, and Environmentalism.”

Brightman’s principal theoretical contributions focus on change and continuity in the anthropological culture concept, and on the conventional character of customs commonly believed to be necessary.

“Nowhere are customs imagined as more naturally inevitable than in the anthropological theories of hunter-gatherer societies,” he explains. “In most of these societies, for example, men specialize in big-game hunting and women in plant collection. This is usually ‘explained’ in anthropology by one or another supposed female incapacity that limits women’s hunting. But it’s ontology (including theological ideas) and gender politics, not primary and secondary sexual characteristics, that gets us this recurring division of labor. The revisability of conventions connects with anthropology’s explicit or implicit comparativism, one of the discipline’s defining qualities.”

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago