IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 93, No. 1: March 2014

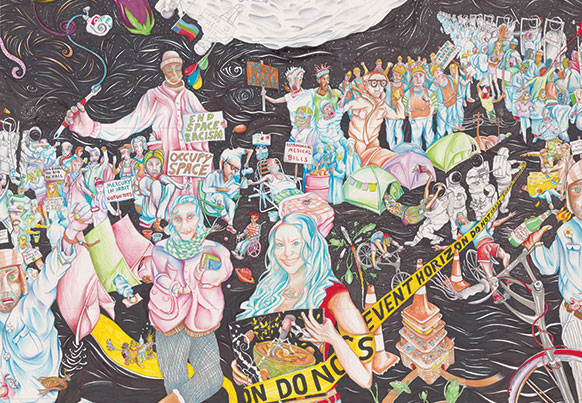

Sketching Infinity

Vance Feldman ’05 is busy drafting what may be the longest illustration in the world.

By Lauren Cooper ’16

The universe of Vance Feldman explodes with jumbled houses, bridges, and aqueducts, businessmen shaking hands, and dolphins jumping out of rivers. To call his work monumental would be something of an understatement. Modestly titled ForeverScape, his drawing rivals some of the longest art pieces in the world. Currently 675 feet wide—the equivalent of two football fields—ForeverScape is assembled out of 735 sheets of letter-size paper and grows wider each day.

The work began in September 2009, when Vance was between jobs and found himself sitting in a bar with a ream of paper. He started aimlessly sketching a landscape, and when the first page ended saw no reason to stop. The first 100 pages or so, drawn in ballpoint pen, feature a smoggy industrial landscape littered with crowded buildings twisting into each other and spilling onto the road, with barbed wire fences set to snag innocent hummingbirds. These give way to apocalyptic scenes of civilization swallowed by the sea. Squid and clownfish lazily swim above a submerged city, whose buildings are wreathed in slimy weeds. Skyscrapers tickle the belly of a whale. One scene depicts several men attempting to subdue what appears to be the Loch Ness monster. Later, after Vance switched to using a Sharpie, the sea became the sky, and the viewer observes a psychedelic rendition of outer space, filled with boats and clams and astronauts in reclining lawn chairs playing badminton.

Lawn chairs pay homage to Prof. Michael Knutson [art 1982–], who once told Vance that all he painted for several years was lawn chairs. Knutson likes the piece so much that he shows it to his art classes every year. The piece, he says, demonstrates “an incredible imagination, focus, and energy.” In a subtler way, it also evokes a childhood loss and a lesson Vance learned at Reed.

![]()

Vance’s interest—you might call it an obsession—with drawing began early. When he was 10 years old, his father was diagnosed with terminal bone cancer. Vance drew a picture for his father for each of the 92 days he spent in the hospital before he died. These pictures were not mere doodles but elaborate sketches of animals Vance found in nature books. This need to keep drawing did not stop with his father’s death—Vance used it as a coping mechanism, taking refuge from his grief.

ForeverScape is in some ways an after-echo of that experience, but with greater sophistication and touches of humor. In a brief gesture of whimsy, Vance has hidden buckets throughout the scape, like the one sitting on an oversized picnic-table-turned-tunnel to a fraying railroad track that is tended by an astronaut suspended over a giant sinkhole.

Even now, with a day job as an interactive software developer, he just keeps pouring out pages. His favorite part of ForeverScape features a rusting and broken Statue of Liberty, 80 pages tall, presiding over a New York overgrown by seaweed with spaceships capsizing in the water at the statue’s feet.

Working on a massive, ever-expanding piece of art raises imposing logistical issues. Vance burns through a new Sharpie every couple of days and was actually selected by the manufacturer as Sharpie Fan of the Week. He stores ForeverScape in a fireproof box in an undisclosed location from which it is rarely removed; he draws a page, scans the page into his computer, and places the page safely in the box. At any given moment, however, he does carry around 50 or 60 pages in a padded, zippered cloth binder.

During our interview at the Lutz Tavern, one of his more frequented haunts of productivity, Vance demonstrates how ForeverScape’s pages can align either horizontally or vertically and still make a cohesive whole.

Vance credits a class with Prof. Hyong Rhew [Chinese 1988–] for one important aspect of ForeverScape—not agonizing over mistakes. Lacking confidence in his class performance, Vance told Rhew that he intended to prepare for the final by going back through all of his old notes. Rhew replied, “Forward only”—encouraging him to study by reading texts that lay just beyond his understanding. By abandoning the methods that had proved ineffective, he would approach the concepts in a new and more fluid manner, Rhew believed. Vance aced the final and passed the course. Ever since, the only direction he has taken is forward.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago