Study Guide Children and Education

Table of Contents

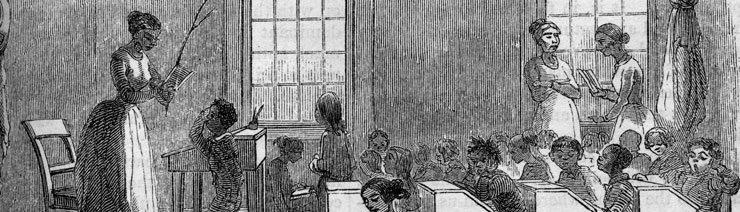

Wheelock's Indian School (Moor’s Charity School)

One of the only other extensive records besides Mayhew’s Indian Converts that we have about New England Algonquian children and education from this era are the letters from the children at Eleazer Wheelock’s “Indian School” (Moor’s Charity School) in Lebanon, Connecticut and the writings of Rev. Wheelock himself (Wheelock published nine narratives between 1763 and 1775). These letters provide an important context for understanding the lived reality of Algonquian children in Puritan schools. Unlike the Wampanoag students on Martha’s Vineyard, Wheelock’s students were selected from a variety of tribes in the region and were educated expressly to become missionaries to their people and to other Native communities (McCallum 16). Education for girls and boys differed: both were educated in rudimentary secular and religious studies; boys also learned husbandry (farming and resource management), while girls were educated in “housewifery”—that is, “whatever should be necessary to render them fit, to perform the Female Part, as Housewives, School-mistresses, Tayloresses, &c.” (McCallum quotes Wheelock’s First Narrative, 16). The letters from the students to Wheelock depict the trials that the students faced and their recurrent lapses into alcohol, sexual intimacy, and the like. In this sense Wheelock’s students were typical youngsters in New England for this time (and perhaps today). Unlike many youngsters, however, these students were economically dependent upon their schoolmaster. This dependency is evident in the way they address and relate to Wheelock.

One of the only other extensive records besides Mayhew’s Indian Converts that we have about New England Algonquian children and education from this era are the letters from the children at Eleazer Wheelock’s “Indian School” (Moor’s Charity School) in Lebanon, Connecticut and the writings of Rev. Wheelock himself (Wheelock published nine narratives between 1763 and 1775). These letters provide an important context for understanding the lived reality of Algonquian children in Puritan schools. Unlike the Wampanoag students on Martha’s Vineyard, Wheelock’s students were selected from a variety of tribes in the region and were educated expressly to become missionaries to their people and to other Native communities (McCallum 16). Education for girls and boys differed: both were educated in rudimentary secular and religious studies; boys also learned husbandry (farming and resource management), while girls were educated in “housewifery”—that is, “whatever should be necessary to render them fit, to perform the Female Part, as Housewives, School-mistresses, Tayloresses, &c.” (McCallum quotes Wheelock’s First Narrative, 16). The letters from the students to Wheelock depict the trials that the students faced and their recurrent lapses into alcohol, sexual intimacy, and the like. In this sense Wheelock’s students were typical youngsters in New England for this time (and perhaps today). Unlike many youngsters, however, these students were economically dependent upon their schoolmaster. This dependency is evident in the way they address and relate to Wheelock.

This dependency was part of the changing landscape of Native life in eighteenth-century New England: children were increasingly indentured out to whites or sent away to white schools. As the letter from Mary Occom in the archive shows, students could not always count upon the support of their families during this era. Mary Occom—the wife of minister Samsom Occom—repeats rhetoric used by students at the school itself. After misbehaving, the students often wrote letters apologizing to Wheelock describing themselves similarly as vile, degenerate, and subservient to Wheelock (and by association, to God). Mary Occom’s letter is of particular interest because we have a number of writings about her family by minister Samson Occom, including his autobiography and his account of the Montauk Indian Tribe, of which his wife was a member. Mary Occom’s letter is also usefully juxtaposed with information we have about how other Algonquian families viewed their children. For example, the support offered by the family of Simon Athearn’s servant (see the section on corporal punishment) contrasts sharply with Mary Occom’s allegiance with Wheelock. The letter helps reveal the changing attitude towards children from within the community and by the children themselves. These changes in the perception of children’s rights by children and their families alike may be the result of both the internalization of white views as well as economic necessity. Writers of letters such as Mary Occom constitute an intrinsically biased sample as they are themselves literate and hence are successful “survivors” of white-style schooling. Similarly, as indentured children grew up, returned to Algonquian communities, and had children of their own, they were more likely to have internalized and naturalized the treatment and punishment they received. Whereas Athearn’s servant had “kindred who might use “vtered violant words to the great afrightning of [the master’s]… wife” and “Caryed away,” the wounded boy, parents who had themselves been beaten as children without an recourse might (ironically) be less inclined to help their children. The economic dependency that characterized Native life on the island in the second half of the eighteenth century may have further made parents less likely to sympathize with their children or interfere. Women who, like Mary Occom, was often forced to beg whites such as Eleazer Wheelock for money to buy food and basic necessities, may have been less likely to be sympathetic with their children’s disobedient stance towards their patrons.

Items Related to Wheelock's Indian School in the Archive

Harvard Indian College < Previous