Study Guide Children and Education

Table of Contents

Children's Conversion Narratives

During the eighteenth century “conversion narratives” by children became increasingly common and popular. The traditional author of Puritan spiritual autobiographies was a minister or lay leader such as John Bunyan, Richard Baxter, Thomas Shepard, John Winthrop, Edward Taylor, or Jonathan Edwards. Women also wrote spiritual autobiographies (for example Mary Rowlandson), but these were more the exception than the norm. The spiritual autobiographies provided a model for the average Puritan, each of whom had to produce their own public account of their conversion in order to gain church membership. The model conversion narratives for the Wampanoags on Martha’s Vineyard would probably have come from white church goers on the island as well as the conversion accounts from Algonquians in Natick.

As Daniel Shea notes in Spiritual Autobiography in Early America, Puritan conversion narratives were highly formulaic (Shea 90). The question of whether a conversion had taken place was not the issue: rather, the testimonies were designed to convince church elders the “presence of grace was evident in their experience” (Shea 91). This motivation is surely Mayhew’s as well: the question is not whether the Wampanoags thought they were Christians; rather the question is whether God’s saving grace was evident in their experience. In other words were they part of the elect? The format for this story was also fairly predictable. Edward Taylor mapped out his story as having two parts: conviction and repentance (Shea 100). Conviction consists of an initial Illumination, which in turn changes the Will to be towards God. Repentance is divided into two stages as well: Aversion (“whereby the heart is broken of[f] from Sin) and Conversion (“whereby the Soule is carried to God in Christ”) (Shea quotes Taylor, 100-101). This pattern holds for many other Puritan conversion narratives, including many of the biographies included in Indian Converts. Once the conversion occurs, however, the Christian may often still stumble: it is this arduous journey towards God with recurrent traps and falls that is depicted in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. The true Christian, however, returned to the path to God’s Celestial City, even when momentarily delayed. The falls (and returns) from grace depicted in Indian Converts typify the genre.

Eighteenth-century conversion narratives about children are of particular interest as they mark a change in the vision of childhood. Whereas first generation ministers like Thomas Hooker had felt that even children of ten or twelve years were not yet rational enough to understand “the mysteries of life and salvation” (Brekus 302, 313 quotes Hooker’s The Unbelievers Preparing for Christ [1638]), Enlightenment ideology encouraged Americans to think of children in a more hopeful light. Even children as young as four were believed possible of receiving saving Grace. The conversion of children provided hope to New Englanders in the midst of the apocalyptic fervor of the Great Awakening. The conversion of Phebe Bartlet as transcribed by Jonathan Edwards is perhaps the most famous of this genre. These narratives provided the natural conclusion to the daily recitation of the Catechism. These stories are often mediated not only by the author, but by adult family members. As such, they provide a good record of the idealized child as seen through the eyes of the community.

Items Related to Conversion Narratives in the Archive

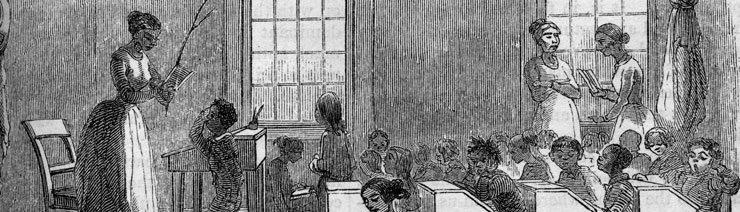

Corporal Punishment < Previous | Next > The Schoolhouse