Study Guide Children and Education

Table of Contents

The Schoolhouse

New England colonies were unusual in colonial American for the emphasis they placed upon education for male and female children. Beginning in 1642, the Massachusetts Bay Colony legislators required that all children had to be taught to “read & understand the principles of religion & the capitall lawes of this country” and in 1647 Massachusetts Bay Court required that any town of at least 100 families had to pay for a grammar school (Teaford 290). Better (or wealthier) students went on to secondary school or perhaps Harvard College. Even so, many towns found it was cheaper to pay the fine for non compliance than to pay a schoolmaster (Teaford 294-96). The records from Edgartown regarding building a schoolhouse and paying the schoolmaster reveal the costs incurred by towns to meet this standard.

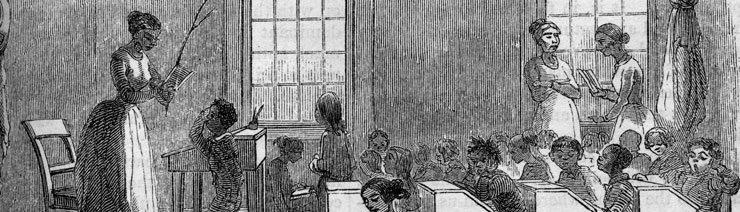

If towns were required to build schools, they were not required to make them luxurious. Schoolhouse buildings in colonial New England tended to be “small, mean, and primitive” (Axtell 170). The schoolhouse in Edgartown was only “twenty feet Long Sixteen wide and Six in ye upright”; yet it was typical in size of the schools found in the region. The First School House in Oak Bluff is also standard design: “frame and clapboard…with perhaps a small loft above the main room” to hang a bell and possibly an “entrance foyer with a closet” (Axtell 170-71). Windows were small so most of the light came from the fireplace. The layout of the room resembled a miniature meetinghouse, with the schoolmaster taking the place of the pulpit: “Three sides of the room were lined with long plank desks attached to the walls, in front of which the pupils sat—with what acute discomfort we can readily imagine—on backless plank seats, awed side upwards, supported on legs driven into auger holes and often projecting above the planks. And at the end of the room, opposite the entrance stood the schoolmaster’s large table, the symbol and locus of authority (Axtell 171).

If towns were required to build schools, they were not required to make them luxurious. Schoolhouse buildings in colonial New England tended to be “small, mean, and primitive” (Axtell 170). The schoolhouse in Edgartown was only “twenty feet Long Sixteen wide and Six in ye upright”; yet it was typical in size of the schools found in the region. The First School House in Oak Bluff is also standard design: “frame and clapboard…with perhaps a small loft above the main room” to hang a bell and possibly an “entrance foyer with a closet” (Axtell 170-71). Windows were small so most of the light came from the fireplace. The layout of the room resembled a miniature meetinghouse, with the schoolmaster taking the place of the pulpit: “Three sides of the room were lined with long plank desks attached to the walls, in front of which the pupils sat—with what acute discomfort we can readily imagine—on backless plank seats, awed side upwards, supported on legs driven into auger holes and often projecting above the planks. And at the end of the room, opposite the entrance stood the schoolmaster’s large table, the symbol and locus of authority (Axtell 171).

The frontispiece to the Primer for the USE of the MOHAWK CHILDREN (1786) reflects the classic arrangement well. Like swaddling clothes or walking stools, the hard seats and barren interiors were intended to create “upright” citizens out of the animalistic children. The children were not pampered: schools were often bitterly cold as parents supplied the wood (Axtell 172). One eighteenth-century child recalled the prevalence of “blue noses, chattering jaws, and aching toes” (Axtell 171).

On the island, both whites and Wampanoags served as schoolmasters: Wampanoag schoolmasters and mistresses included James Sepinnu (IC 73, Indian Schoolmaster/teacher 1659-63) and Mehitable Keape (the daughter of Job Soomannan [IC 51-2, 105, 110-13]) who kept school at Christiantown and whose house was used for worship (Segel & Pierce).