Musth and Communication

Biology 342 Fall 2010

Andrea Padgett

Adaptive Value

The Benefits of Musth and Musth Signaling

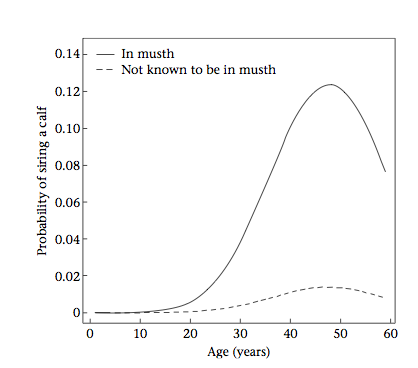

The ability to go into musth dramatically increases a male elephant’s chances of reproductive success. While adult males are capable of producing offspring year-round (Eisenberg), and produce viable sperm before they reach the normal age for musth (Poole 1999) an estimated 75-80% of calves are sired by musth males (Ganswindt 2010). Not only do musth males actively seek out females and guard them (Rasmussen, H. B. 2008), but musth males have dramatically higher parternity success rates than nonmusth males (Hollister-Smith 2007). While age, and therefore size, play a role in paternity success (Rasmussen, H. B. 2008), most musth males, regardless of age, have higher paternity success rates than nonmusth males (Figure 4) (Hollister-Smith 2007).

Figure 4: The paternity rates of musth vs. nonmusth males at various ages.

While the aggressive, hyper-sexual behavior of musth males plays a role in this, an element of female choice is apparent here (Moss). Mating attempts by larger males are more likely to be successful than those made by smaller males. While the normal pattern of elephant mating involves the female fleeing the male for short distances, female African elephants have actually been observed to aggressively follow musth males in attempts to mate. Females have actually been observed to flee from the advances of smaller non musth males (Rasmussen, H. B 2008).

Going into musth allows a male to jump to the head of the line in terms of dominance. Elephants grow throughout most, if not all of their adult lives (Hollister-Smith 2007). In nonmusth males, dominance is determined by size and therefore age. However, musth males always outrank nonmusth males, regardless of size. The reason for this is generally thought to be related to the asymmetrical rewards presented by mating (Sukumar 114). In short, musth males are aggressive and fueled by a powerful desire to mate. A nonmusth male, when encountering a musth male, is at a disadvantage. He is not only less threatening, but the rewards for dominating his rival are less desirable to him. It is often in a nonmusth male’s best interest to back down.

The ability to communicate musth state and interpret the musth states of others is beneficial to both male and female elephants. The ability to send chemical signals, which do not require the sender’s presence, allows sexually active elephants to locate each other while minimizing contact between aggressive musth males and nonmusth males or non-fertile females (Bagley).

When exposed to the urine of musth males, captive male elephants preformed significantly fewer flehmens than when exposed to the urine of males not in musth (Hollister-Smith 2008). Such response patterns, researchers hypothesized, indicates non-musth males respond more quickly to the urine of aggressive, potentially dangerous musth males. Further, they reason, repeated flehmens of non-musth urine may allow elephants to determine how close the male that produced the urine is to entering musth. Younger males were found to exhibit higher levels of avoidance and repeated testing of urine than older males when exposed to musth urine. This is appropriate, since smaller males would be in more danger than larger males. Males who had been previously housed with other males sought out a higher degree of information when presented with urine. Males who are in constant contact with other males would benefit form more accurate information about the musth states of other males. In these cases, the subordinate males showed a higher degree of avoidance.

Females not in musth display similar responses as nonmusth males when exposed to the urine of musth males (Shulte 1999). They also perform fewer flehmens on musth urine, suggesting they too benefit from quickly fleeing the areas of musth males. Cyclohexanone, a component of musth urine, has been found to induce groups of females to form a ‘star’ formation, circling their young in a defensive manor (Rasmussen, L. E. L 1999). Such behavior would protect the young from aggressive musth males.

The responses of nonmusth males to auditory signals from musth males is similarly appropriate, with the nonmusth males fleeing the source of the sound (Poole 1999). Musth males have been found to approach the source of the sound, even if it comes from a larger male. Musth is energetically costly to maintain, and it’s possible that musth male producing the sound is therefore in a weaker state than the responding male. Additionally, fertile females are drawn to the calls of musth males, giving other musth males an incentive to locate the source of the call.