Musth and Communication

Biology 342 Fall 2010

Andrea Padgett

Mechanism

The exact physiological characteristics of musth have not yet been fully described. It has long been known that musth is correlated with heightened levels of testosterone (Poole 1984). More recent studies indicate that musth temporal gland secretion and urine dribbling are induced by elevated levels of androgens (Ganswindt 2005). Small, short-term increases in androgen levels do not usually bring about musth, indicating that a sustained, relatively high increase in androgens is necessary to induce musth. Instead, small increases in androgen levels have been observed to bring about a sexually active, but non-musth state (Rasmussen, H. B. 2008), where the males will be sexually active, but not display urine dribbling or temporal gland swelling. It is therefore presumed that a small increase above baseline androgen levels is needed to trigger sexually active behavior, but a much larger and more sustained increase is needed to trigger musth. The onset of musth is associated with aggression, and aggressive males are known to have increased androgen and decreased glucocorticoid levels (Ganswindt 2005). Though both produce unusual psychiatric effects in the organism, there is no proven connection between the effects of lysergic acid diethylamide and musth, and large doses of the chemical have been shown to be harmful to elephants (West).

Elephants utilize numerous methods of communication to convey information about their musth state to females and other males. One known method of communication is through urine (Hollister-Smith 2008). Since urine is a byproduct of short-term metabolic functions, and thus it’s composition changes with the elephants internal chemistry, it is likely an honest signal (Schulte 1999). Studies of captive male African elephants showed that males were able to differentiate the urine of males in musth from non-musth males (Hollister-Smith 2008).

Experiments with captive female elephants indicate that urine is used for male-to-female communication as well (Schulte 1999). In an experiment by Schulte and L. E. L. Rasmussen, a correlation was observed between the estrus cycle of female elephants, testosterone content of male urine, and female interest in urine. Specifically, females were always more responsive to musth urine than nonmusth urine, and females nearer to their fertile phase were more responsive than nonfertile females. Additionally, exposure to cyclohexanone, a component in musth urine, has been shown to induce groups of female elephants to form a ‘star’ surrounding their young (Rasmussen, L. E. L. 1999).

Secretions from the temporal gland are also used to signal musth (Rasmussen, L. E. L. 1999). Male Asian elephants have been observed to show interest in their own secretions during and proceeding musth. Female Asian elephants show an increased interest in the temporal gland secretions of musth males (Figure 2)

.

Figure 2: A female examines a male's temporal gland secretions

The dual use of temporal gland secretions and urine as signaling mechanisms, combined numerous components of temporal gland secretions, allow elephants to send chemical signals with multiple durations (Rasmussen, L. E. L 1999) Lighter, more volatile components of temporal gland secretions may function as short-duration olfactory signals and may play a role in musth self-awareness. Less volatile molecules may gain access to the vomeronasal organ via flehmens, a behavior characterized by touching a substance with the trunk, then bringing the tip of the trunk into the mouth.

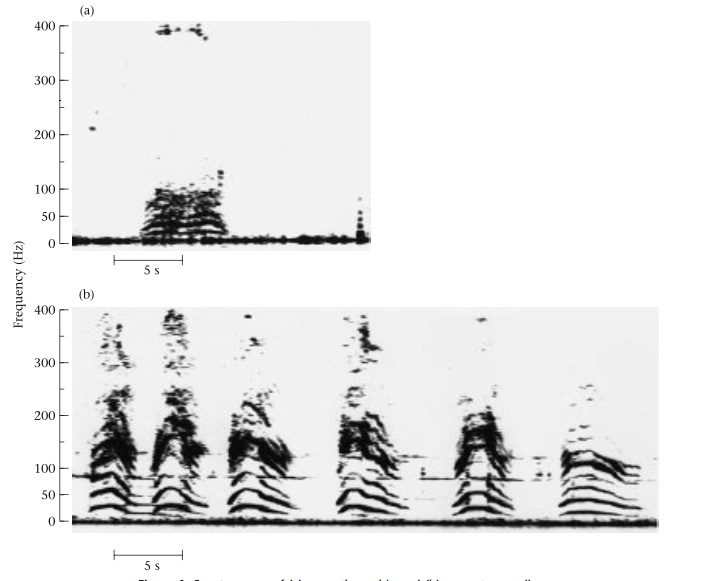

In addition to chemical signals, elephants incorporate vocal signals to indicate musth or receptiveness to mate (Poole 1988). Males in musth have been found to give a distinctive low call known as a musth rumble (Figure 3 a). Groups of females have been known to produce responses known as the estrus call (Figure 3 b) (Poole 1999) or female choruses (Poole 1988) upon hearing a musth rumble or when presented with musth urine-soaked ground or a musth male. Playback experiments indicate musth males are drawn towards estrus calls, while non-musth males move away from them (Poole 1999). Similar behaviors are shown when nonmusth males are exposed to musth rumbles, Interestingly, smaller musth males will still approach the source of musth rumbles that are produced by larger males. When exposed to musth calls, estrus female African elephants begin sending out chemical signals by urinating, defecating, and producing temporal gland secretions.

Figure 3: Spectrograms of a) musth rumble and b) estrus call