IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 92, No. 3: September 2013

Last Lectures: We salute retiring (and not-so-retiring) professors.

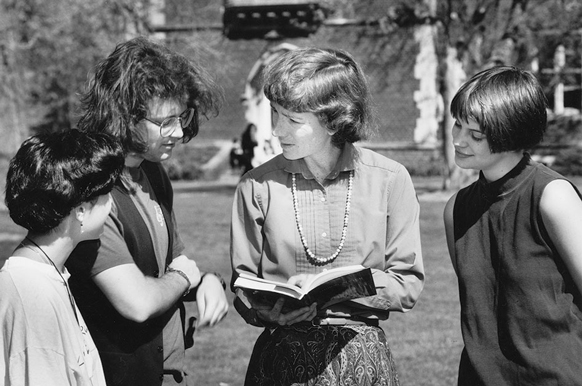

Prof. Ellen Keck Stauder [English, 1983] (continued)

By Romel Hernandez

For many years, Prof. Stauder used an ingenious—and irreverent—method to teach her poetry students the difference between meter and rhythm. She played a recording of her long-haired dachshund Willie lapping up water from his bowl in perfect iambs.

Meter goes on and on, like the dog drinking. Rhythm, however, shapes time, stressing different parts of a poem in different ways. “My students thought I was insane to play the recording of the dog,” she says wryly, “but they never forget the distinction.”

Stauder needn’t have worried—the David Eddings Professor of English and Humanities has made an indelible impact on generations of students.

“Ellen Stauder may have had more influence on where I am in my career than anyone else,” says Greg Barnhisel ’92, who chairs the English department at Duquesne University. “Her English Literary History class did a brilliant job of teaching the most canonical, conservative overview of English literary history from a feminist and historicist perspective. Even after 25 years, my understanding of the development of English literature is based on that class.”

As a teenager, Stauder was an accomplished clarinetist and dreamed of playing in the symphony until a hand injury cut short her musical career. She then got interested in the history of music and culture, and the work of Ezra Pound. Stauder earned a BM at the Eastman School of Music, an MA in English at the College of St. Rose, and a PhD in the history of culture at the University of Chicago.

“She’s got deeply, deeply held integrity. She really is who she is, no matter what she’s doing,” says Prof. Gail Sherman [English 1981-90]. “And she has a very deep sense of caring for Reed.”

While Stauder held administrative positions including associate provost and dean of the faculty, her greatest legacy has been as a teacher and mentor to so many students over the decades.

“I learned to go where the poems want to go on that day in my students’ hands and my hands,” she says, summing up her teaching philosophy. “If I could help the discussion come along and help students more fully say what they wanted to say, that was good.” She was never satisfied with getting her students to engage poetry intellectually; she wanted them to love poetry: “I wanted to inculcate in students the great pleasure of poetry, and that when you understand a poem, what an amazing thing that is to understand.”

Former students single out her uncommon warmth, her curiosity, her ability to see the extraordinary in what might seem ordinary—all qualities that have shaped her career at Reed.

“Wherever I turn with a blank stare, Ellen always seems to be uncovering a hidden world,” says Alina Serebryany ’09. Her influence, she added, “reminds me to crane my neck and look, and take a little more time to look.”

Stauder served as dean (she is proudest of establishing the Reed Center for Teaching and Learning) until poor health prompted her to step down in 2011. After taking time off, she returned last spring to teach one more class: “Truth and Beauty in Modern Poetry.”

In retirement, she plans to pursue her passions for photography and gardening, and holds out the possibility that she may return to campus to teach and continue that pursuit for truth and beauty.

Fittingly, the college planted a yellow magnolia tree in her honor near the entrance to the Hauser Library. As Prof. Sherman says: “Every day as people walk into the library, if the beauty of that tree has an impact on them, it will be Ellen’s sustaining legacy to the college.”

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago