IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 90, No. 4: December 2011

Apocrypha: Traditions, Myths, & Legends

Origin of the Scrounge

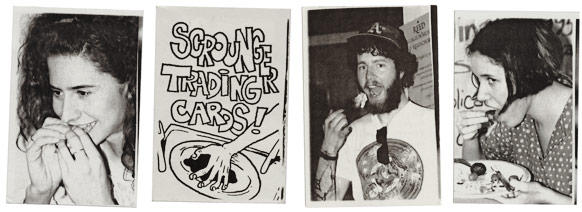

Scrounger trading cards, issued in fall ’93, included special chowline monikers. From left: “Minneapolis,” “Krack,” and “Skunk.”

Tracking down the first fork-wavers.

By Raymond Rendleman ’06

Walk into commons and you’ll see that the venerable practice of scrounging is alive and well. Students hover unobtrusively near the drop-off window, fork in hand, hoping that you’ll donate some tasty morsels to their cause. They seem as much a part of the campus ambience as the canyon ducks and the Oresteia.

But scrounging wasn’t always accepted at Reed. In 1962, the Honor Council found a junior guilty of lying about “mooching in commons.” In a letter to the defendant reprinted in the Quest, honor councilor Don Kates ’62 wrote, “Your defense was that you had taken food which otherwise would have gone to waste. To sustain this defense you must needs answer ‘no’ to the question ‘Have you ever asked anyone to get extra food for you?’”

Credit goes to Mary McCabe [commons and dorms director 1958–78], for allowing the practice to take root. Although Mary was known for her mouth-watering clam chowder, she also superintended a period of social revolution that transformed everything from hairstyles to dining etiquette.

In 1966, after working for Mary at commons for a month or two, Nick Heyer ’67 figured that a free meal was not an unreasonable benefit of his work. “I started arriving early and simply helping myself,” he recalls. “Having met no objections, I continued the process.” Mary eventually confronted him, but he somehow talked himself out of trouble.

One day Nick ran into a freshman who was on a diet. She would eat what she wanted, then give him her leftovers as part of a portion-control plan. Soon a half-dozen students (who preferred the term “scrounger” to “moocher”) were sitting at a table near the dishwashers. “Everyone knew to drop off their leftover food for us,” Nick says. “I don’t think we saw this as a movement—we just chatted about whatever it is we wanted to chat about.”

Outsiders sometimes scoff at the idea that Reed students don’t have enough money for food, but the truth is that many students live on a shoestring budget. For Nick (and others such as Steve Jobs), scrounging was simply a way to keep costs down.

The practice aroused remarkably little controversy until April 8, 1982, when the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page story with the sensational headline “Freeloaders Ambush Paying Customers at College Mess Hall.” The story quoted concerns from a county health officer and the cafeteria head, Jim O’Brien of Saga Corporation, saying that scrounging cost Saga $15,000 a year.

Responding to trustee concerns, President Paul Bragdon [1971–88] wrote, “Yes, we knew the reporter was here. Yes, since he wouldn’t go away, we cooperated with him. Yes, we kept our fingers crossed that the story would die.”

Some alumni wrote in to praise the practice, however. “I hope the faculty, student body, and administration were more amused than embarrassed,” Chas Clifton ’73 declared. “It did my heart good to know that a stalwart tradition was being continued.”

A survey of Reed students that spring showed that only 68 found the practice “offensive;” 143 said it was “a nice tradition,” and 288 said it was “a good use of leftovers.”

Meanwhile, scroungers developed their own code of ethics. William Abernathy ’88 penned the Commandments for Scroungers, whose first rule is: “Thou shalt not wrest thy bread from the tray of another without asking.”

In the early ’90s, students even introduced scrounger trading cards. The idea was simple: buy a scrounger a meal, and collect his or her card. The cards featured scroungers such as “Fearless Forker,” who lists her life source as “chicken strips with honey mustard,” and her weaponry as “standard fork and long arms.”

Ironically, Nick eventually became a public health epidemiologist and holds a more skeptical view of scrounging today. “I’m still fairly frugal—I own a regular old TV instead of a flat screen,” he says. “But thinking back on it now, I wonder, ‘How did I go for everyone else’s gnawed-on scraps?’”

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago