The Parthenon

Introduction

"Pericles’ answer to the people was that the Athenians were not obliged to give the allies any account of how their money was spent, provided that they carried on the war for them and kept the Persians away. ‘They do not give us a single horse, nor a soldier, nor a ship. All they supply is money,’ he told the Athenians, ‘and this belongs not to the people who give it, but to those who receive it, so long as they provide the services they are paid for. It is no more fair that after Athens has been equipped with all she needs to carry on the war, she should apply the surplus to public works, which, once completed will bring her glory for all time, and while they are being built will convert that surplus to immediate use. In this way all kinds of enterprise and demands will be created which will provide inspiration for every art, find employment for every hand, and transform the whole people into wage-earners, so that the city will decorate and maintain herself at the same time from her own resources." Plutarch, Life of Pericles 12. |

|

+ enlarge |

In c. 448 BCE, after the conclusion of hostilities between Greece and Persia, the statesman Pericles motivated an ambitious building program. The core of his program was the restoration of the Acropolis (which had been destroyed by the Persians in 480 BCE) with the Temple to Athena Parthenos (the Parthenon) as its centerpiece.

The architects for the project were Ictinus and Callicrates, who designed a truly ambitious Doric temple combined with Ionic elements.

- 447 BCE Construction begins

- 438 BCE Dedication of the Temple and Cult Statue

- 432 BCE Completion of the Temple and its Sculptures

Fabric

The Parthenon was built entirely of Pentelic marble except for the limestone foundation. This was unprecedented. On the Greek mainland no Doric peripteral temple had been made of marble throughout its entire fabric before the Periclean period.

Dimensions and Style

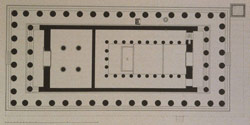

In terms of the scale and proportions of the temple, the architects displayed great ingenuity. The Parthenon had eight columns on the short ends and seventeen on the long sides. This octostyle facade had no precedent in Greece. Its effect also allowed some differences from the standard Doric design.

a) Porches: Shallow prostyle porches, with six columns, at either end of the cella replaced the deep pronaos and opisthodomos.

b) Cella: The cella's width was determined by the dimensions of the facade. Because of the increased number of columns, the cella was wider. For the first time, a Greek architect attempted to design interior space instead of merely enclosing it with four walls and a roof. The goddess here was not backed against the rear wall of a long tunnel-like nave but was rather set well forward, within her own colonnade on three sides, creating a free play of space all about the great image. Visitors were meant to walk around the great image of Athena, which was made of gold and ivory and decorated extensively with sculptural reliefs.

c) Back Chamber: in addition to the cella and the two porches, there was now a back chamber, entered from the opisthodomos. This room, the Parthenon proper, was perhaps used as a treasury.

Overview: Decoration < Previous | Next > Parthenon: Refinements