Tameability and Domestication

Bio 342 By Alex Winters

Introduction

What is tameability?

Tameability is a behavioral measure of the ability of an animal to be domesticated. It is usually measured by an animal’s fear response at the approach of a human. Tameability can also be seen as a kind of index showing how well an animal would adapt to living with humans.

Tameability and Domestication

Taming an animal, making it not fear or lash out at humans, is the first step to domestication. To begin the process of domestication, one must start by selecting animals on the basis of tameability.

Selection Effects

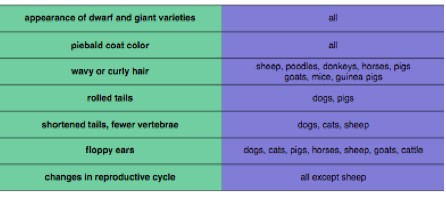

By selecting for this one key trait, many different animal populations have become domesticated, and the result of the selection has been very similar. Changes in size, coat color, fertility, neurochemicals, and retention of juvenile traits have been observed in most if not all domesticated animals in surprisingly similar ways, especially in the so-called “big five” (cows, goats, sheep, horses, and pigs) (Figure below from Trut 1999).

Recent studies of tameability using foxes as a model (Trut 1999; Belyaev 1979)

The most well known experiments on tameability to date

were

performed (and are still ongoing) using farm-foxes (Vulpes

vulpes) by Trut and Belyaev in the former USSR and now in Russia. The

experiments begun in 1959 with Belyaev who was then the head of fur

breeding in Moscow. He noticed the changes that took place in

domesticated foxes and how

they compared to other long-domesticated animals.  Belyaev designed an

experiment to select only for tameability, convinced that tameability

was a trait

under genetic control.

He started with partially tamed foxes that had been bred for their fur

and examined their reactions to human experimenters. In every

generation only the most tame foxes were chosen to breed

(about

4-5% of each generation). Now 40 years later they are

affectionate and bond easily

with people. When

experimenters approach their cages the whine for attention and when

not caged they follow the experimenters around like dogs. A

number of

surprisingly morphological changes have also occurred in the test

population, including

coat pigment loss, the appearance of pie-balding, floppy ears, rolled

tails, shorter tails and legs, cranial changes, and the partial

abandonment of reproductive cycles in favor of more continuous

breeding. These changes are strikingly similar to those that

occur in other domesticated populations and are very rare in control

fox populations.

Belyaev designed an

experiment to select only for tameability, convinced that tameability

was a trait

under genetic control.

He started with partially tamed foxes that had been bred for their fur

and examined their reactions to human experimenters. In every

generation only the most tame foxes were chosen to breed

(about

4-5% of each generation). Now 40 years later they are

affectionate and bond easily

with people. When

experimenters approach their cages the whine for attention and when

not caged they follow the experimenters around like dogs. A

number of

surprisingly morphological changes have also occurred in the test

population, including

coat pigment loss, the appearance of pie-balding, floppy ears, rolled

tails, shorter tails and legs, cranial changes, and the partial

abandonment of reproductive cycles in favor of more continuous

breeding. These changes are strikingly similar to those that

occur in other domesticated populations and are very rare in control

fox populations.

Photo from Trut 1999