Bio 332 - Vascular Plant Diversity:

EXAM 3 KEY

The following answers are given as guidelines to the kinds of information I was looking for. Other correct answers may have been possible for some questions, so you should check with me if you have specific questions.

What feature(s) of the biology of this conifer is/are likely to have caused the loss of the remaining portion (one-third) of the unfilled seeds?

Conifers are mostly monoecious, giving them the opportunity to self-pollinate. They also have breeding systems that are highly outcrossing, so deleterious alleles that contribute to inbreeding depression are expected to be found in natural populations at appreciable allele frequencies. A likely explanation is that a third of the unfilled seeds were the result of self-pollination/fertilization, and the resulting zygotes had poor fitness and did not mature into viable seeds.

Would you expect to see the same feature(s) affecting viable seed production in ginkgos?

2. Friedman & Floyd (2001; Evol. 55: 217-231) point out that two competing hypotheses have been debated for a number of years regarding the homology of double-fertilization in the seed plants.

Describe the two hypotheses, and then indicate which you believe is best supported and what the data are which lead you to this conclusion.

Some morphological data (vessel elements) and the similarities around double-fertilization have provided compelling support for the first (gnetophyte/flowering plant clade), while most molecular data now support the second.

3. Outcrossing taxa may give rise to selfing taxa, but the reverse evolutionary transition is rarely seen. From your knowledge of inbreeding depression and the theory of mating system evolution, what might account for this bias in outcomes?

Mating system theory proposes that the magnitude of inbreeding depression will largely determine conditions in which selfing is favored or outcrossing is favored. With high inbreeding depression, we expect populations to evolve towards complete outcrossing, while with low inbreeding depression, selfing has a transmission advantage and is favored. The magnitude of inbreeding depression will also be influenced by the history of inbreeding/outcrossing in a population – a history of outcrossing allows recessive, deleterious alleles to increase in frequency, while constant inbreeding exposes deleterious alleles to selection and keeps their frequency low.

Given an outcrossing population with high inbreeding depression, we might imagine ecological circumstances (e.g. loss of pollinators) in which selfing may be strongly favored, in spite of strong inbreeding depression. As long as the population is not dioecious, selfing may occur with the result that strong inbreeding depression will be expressed in the progeny. As long as selfed progeny are not all dead, production of selfed progeny may still provide higher fitness than “no seeds” produced through outcrossing. At this point, continued ecological selection favoring selfing each generation provides the opportunity to reduce the frequency of the deleterious alleles because they are exposed to selection. If this purging happens quickly enough, the magnitude of inbreeding depression might fall to the point where selfing is favored based on inbreeding depression and the population evolves towards complete selfing, regardless of the presence or absence of the ecological selection. In this manner selfing evolves from outcrossing.

For the reverse transition, we would need to envision circumstances in which selfing is difficult but outcrossing is o.k. (such a scenario seems unlikely), or a circumstance in which deleterious alleles start to increase in frequency in a population such that the magnitude of inbreeding depression rises above the threshold that favors outcrossing. This later scenario also seems unlikely, as deleterious alleles are generally expected to continuously be exposed to selection within a selfing population, and consequently the ongoing purging will always keep inbreeding depression low.

4. Conservation biologists recognize that maintenance of the allelic diversity at a self-incompatibility locus is essential for the reproductive success of any SI plant species.

i) For a gametophytic (GSI) self-incompatibility system, what is the minimum number of alleles that must be present for reproduction to succeed?

A GSI system cannot operate with fewer than 3 alleles (with only 2 alleles, everyone is heterozygous and cross-incompatible).

ii) Provide an argument that would convince conservation biologists that keeping population size large enough to prevent loss of genetic variation through genetic drift would provide a size that will also maintain the allelic diversity at the S-locus.

Frequency-dependent selection will act to maintain allelic diversity at the S-locus in a GSI system, so that rare alleles will be protected from loss by the positive selection they experience when rare. This frequency-dependent selection will act in opposition to drift, and thus any population’s size that minimizes drift will be expected to contain lots of diversity at the S-locus

5. Describe the similarities or differences when comparing self-pollination/fertilization with apomixis (asexual reproduction) with respect to i) meiosis, ii) reproductive assurance, and iii) inbreeding depression.

Self-fertilization is a sexual process in which two (normally haploid) gametes unite to form a zygote. The gametes are haploid by virtue of a meiotic division (which initially produces a spore in plants). For self-pollination, the uniting gametes originated from distinct meiotic divisions. Self-pollination can give reproductive assurance for a seed plant that makes both pollen and ovules in cases where outcrossing is not possible (no other plants or no pollen vectors) – provided that the pollen can easily reach the ovule (or stigma for flowering plants) without the need for a pollen vector. Because of the separate meiotic divisions leading ultimately to gametes, the progeny from self-fertilization are not necessarily identical to their parent (as long as the parent had some heterozygosity). Consequently, the selfed offspring can be homozygous for deleterious recessive alleles that were heterozygous in their parent, and thus they will show inbreeding depression if those deleterious alleles are present.

Apomixis is asexual and only involves mitotic divisions – there is no meiosis. Apomixis can provide reproductive assurance by allowing plants to reproduce when other plants are not available as mates. Because meiosis (and segregation) does not occur, the offspring from apomixis are identical to their parents and will not show any additional inbreeding depression that distinguishes them from their parent.

6. A geneticist was suspicious that the scarlet rose, Rosa asexifolia, is an agamospermous species. She collected cuttings of several genets from a wild population and brought them into an insect-free greenhouse where they were grown to flowering. Once flowering began, the geneticist tried several crossing experiments.

– Flowers on six plants were emasculated (i.e. the anthers were removed from each flower before the pollen had left the anthers) and not pollinated. Flowers in this group of plants failed to produce any seeds

– Starch-gel electrophoresis was used to determine the genotype of each genet at a locus that was variable (the alcohol dehydrogenase locus, ADH). After genotyping the plants, she performed two kinds of crosses to clarify whether or not the species reproduces apomictically.

Cross Type 1: homozygous individuals for a "Fast" ADH allele (genotype=FF) were used as pollen donors for plants that were homozygous for a "Slow" ADH allele (genotype=SS).

Cross Type 2: heterozygous plants (genotype=FS) were self-pollinated.

Both cross types resulted in successful seed production and these seeds were then genotyped at the ADH locus. The observed progeny genotypes confirmed her suspicions, and she concluded that Rosa asexifolia is indeed an agamospermous species.

i. If this species is truly an apomict, why did the emasculated/unpollinated flowers fail to produce seed?

The species may be pseudogamous, in which case the pollen is required (probably for endosperm fertilization) but the pollen does not contribute any genes to the resulting zygote.

ii. What progeny genotypes were observed in the Type 1 (FF x SS) and the Type 2 (FS – self) crosses ?

All should resemble their mom (SS for the first cross, FS for the second), with no segregation or paternal contribution observed.

iii. In an earlier taxonomic treatment of the genus Rosa, researchers had made the claim that Rosa asexifolia is one of the oldest species in the clade and has given rise to a diverse lineage of descendent species. Based on the results from the above genetic analysis, would you agree with this phylogenetic placement of the species (justify your answer)?

Agamospermous speces have been generally observed at the tips of phylogenies and are believed to rarely give rise to diverse clades. The earlier taxonomic placement on the phylogeny is likely an error.

7. The genus Oxalis (Wood Sorrel Family) is quite diverse, with almost 800 named taxa. Species in this genus can be found with flowers that are:

(a) hermaphroditic, and self-incompatible (c) dioecious

(b) hermaphroditic, and self-compatible (d) agamospermous

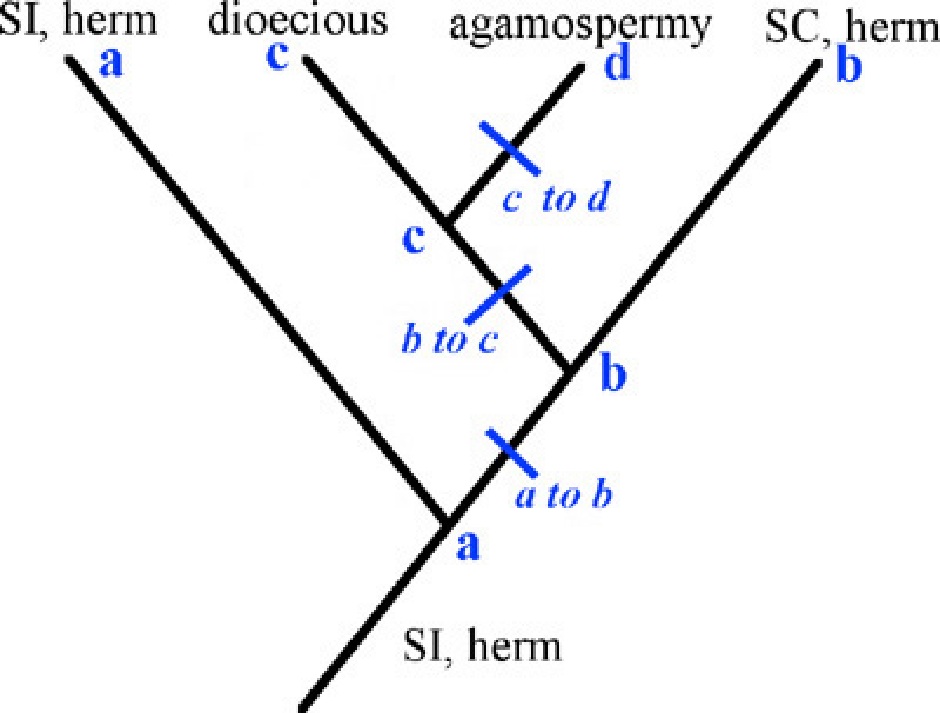

Place these four breeding systems onto a phylogeny where they represent terminal taxa (you can use their single letter designation, a-d) showing an arrangement that you believe reflects the evolutionary relationships among the breeding system in the Oxalis genus. On the phylogeny, indicate the ancestral condition at the base of the genus.

Also show the breeding system for the hypothetical ancestor at every node of the phylogeny, and show along each branch where a new breeding system evolved that differs from the most immediate common ancestor.

Circle one of the evolutionary transitions along the branches shown in your phylogeny and describe what you believe to be the selective reason underlying the shift in the breeding system.

Various answers are possible, with the following caveats:. SI is generally observed to be lost but not gained within families (Dollo parsimony); agamospermous species are unlikely to be ancestral to any of the other breeding systems, and their relatives are most commonly outcrossing;; outcrossing more commonly gives rise to selfing breeding systems, while the reverse transition is less common.

In this example, SI is ancestral. SC evolved because of ecological factors that selected for reproductive assurance, and the selfing individuals were able to purge their inbreeding depression. Dioecy evolved from the SC ancestor due to resource allocation benefits from specialization in male and female functions. Agamospermy evolved as a result of a polyploidy and/or hybridization event that produced a taxon that could not undergo normal meiosis. Alternately, agamospermy was favored due to abiotic selection for reproductive assurance and the perpetuation of a particularly well-adapted genotype.

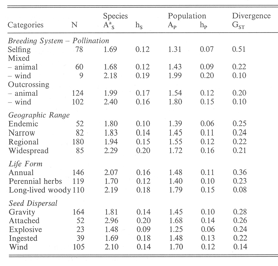

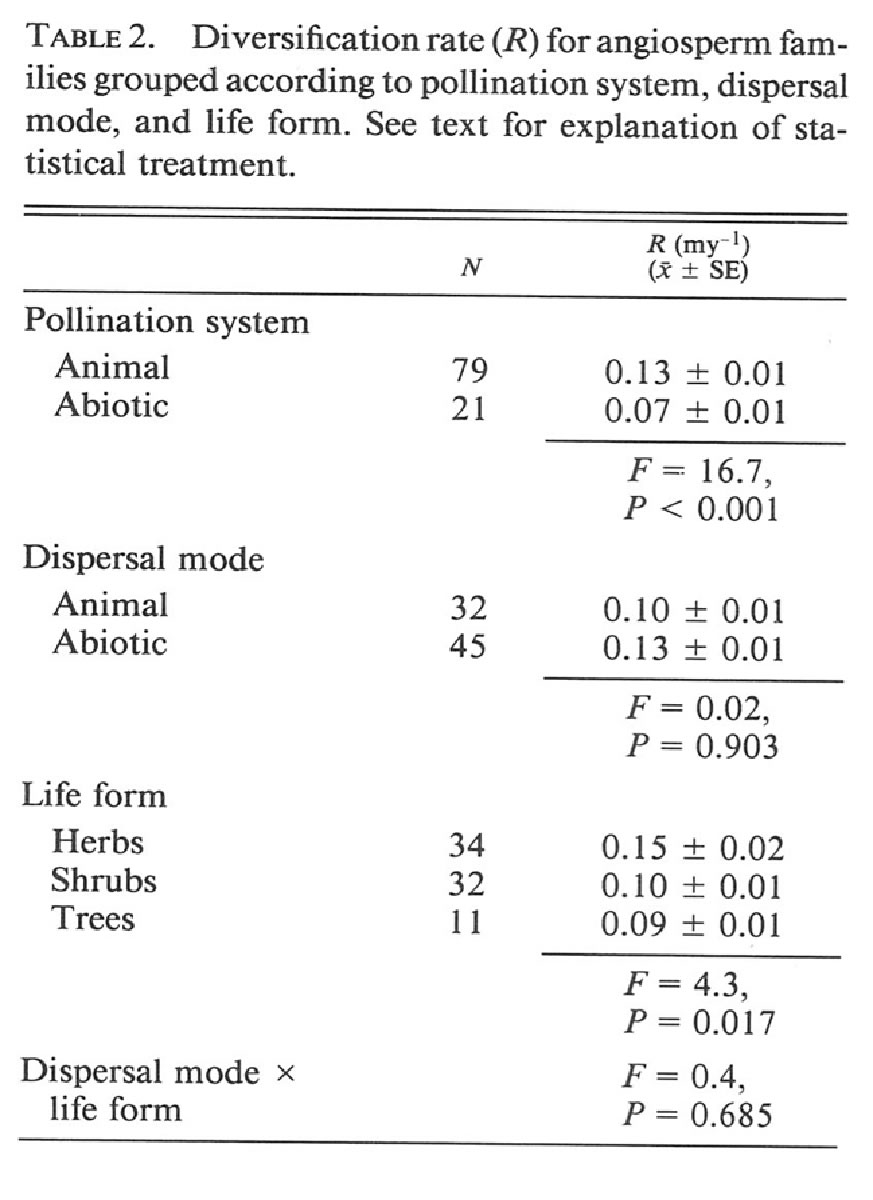

8. The following data provide information related to the roles of biotic (animal) pollen dispersal and seed dispersal in the evolution of flowering plant diversity:

Table 9.1 (Briggs & Walters, 3rd ed.) summarizes the Table 2 is taken from Eriksson and Bremer (1992,

results from genetic studies looking at genetic Evolution 46: 258-266) and describes the rate of

variation and the degree to which populations of a diversification (speciation minus extinction) for

species are genetically diverged. plant families that have the different characteristics

"Gst" is a statistic that quantifies the magnitude of indicated in the Table.

genetic divergence among populations of a species

(0 = all populations of a species are genetically

identical, while 1 = all genetic variation occurs

among populations).

i. CHOOSE either animal pollen dispersal or animal seed dispersal: what is the mechanism by which animal involvement in this process might contribute to increased diversity of flowering plants?

increase rates of speciation:

The primary factor would be natural selection: Animal participation provides a biotic environmental feature that the plants may adapt to via natural selection. Local selection that leads to local adaptation to biotic pollinators and/or seed dispersers increases divergence of populations and also increases the likelihood that the populations may diverge enough to be reproductively isolated if they come into contact.

Animal pollinators might also reduce rates of gene flow and therefore allow for greater divergence through selection (or drift).

Rates of genetic drift can be affected if the animals are especially efficient at their dispersal of pollen and/or seeds, then the plants may be able to persist at ecologically low densities. Persistence with small population size will increase the importance of drift, leading to divergence among populations, which might ultimately lead to reproductive isolation and speciation.

decrease rates of extinction: Animals maybe more efficient at dispersing pollen and seeds than abiotic vectors when populations are small in size. This should allow populations to persist ecologically when small, which should lessen the likelihood they will go extinct.

ii. Describe whether the data in these tables support or reject your mechanism (be sure to specify whether the data in the two tables are giving the same answer -- either supporting or rejecting your mechanism -- or if the data are instead providing conflicting data about your proposed mechanism).

Animal pollination:

Divergence (Gst) is generally higher (more divergence among populations) for animal pollinated when compared to wind pollinated species. Rates of divergence are also significantly higher for animal pollinated plant families. These results would support increased divergence (and thereby speciation) for animal pollinated species. While the increased diversification rate might also support a role for decreased extinction, but only if the increased efficiency of pollen transfer allows for the avoidance of extinction in small populations without simultaneously increasing gene flow between populations (since increased gene flow would actually decrease divergence)

Animal seed dispersal:

Divergence (Gst) does not appear to be different for ingested/attached (animal) seeds when compared to abiotic (explosive/gravity) dispersed seeds. the exception is wind-dispersed species, which have populations that are less diverged than are the animal dispersed species. This later observation is weak support for a role for animal dispersal in promoting divergence (and thereby increased divergence and speciation). However, the data on the effect of dispersal mode on rates of diversification do not support a role for animal dispersal in promoting speciation and/or reducing extinction.

verses composed (under duress)

by the 2012 Bio 332 class

And now we know some botany

we will see the ferns in the many

they’re not sporophytes

like gnetophytes

and that’s the delight of botany

And now we know some botany

build your own phylogeny

you can guess

the reason for

self-incompatibility

And now we know some botany

we’ve really learned a lot you see

from fossil ferns

to vortex turns (of air between pine cone scales)

to (self) incompatibility

And now we know some botany

we hope our brains won’t rot any

we still define

(when ninety-nine)

adventitious embryony

And now we know some botany

it’s taken quite a lot of me

and you can bet

I can’t forget

until I’ve got some rot in me

And now we know some botany

your friends think you’re too zany

tell them about Welwitschia

they’re looking funny atchya?

just remind them of cleistogamy

And now we know some botany

let’s use it to help crop any

new hybrids and cultivars of prominence

hopefully with overdominance

to support farmers that haven’t bought any (heterozygous seeds)

And now we know some botany

even if we forgot any

ovule or spore

pollen or more

we still learned a lot (any!)

And now we know some botany

let’s hope you’ve not forgot any!

for without conifers

cycads and flowers

the world would be terribly rotten-y

And now we know some botany

to help break the monotony

think selection

sans perfection

to help build your own phylogeny

And now we know some botany

from Gentum to agamospermy

terms like “prezygotic”

have made us neurotic

but at least we can see Oemleria

And now we know some botany

to look at plants and spot many

look – this green sprout

will be a tree no doubt

the resemblance is un-canny