Exam 2

1. For heterosporous plants, self-fertilization will contribute to the establishment of polyploids if individual plants that self are producing high frequencies of diploid spores (leading to diploid female and male gametophytes and gametes) due to bad meiosis (=non-disjunction). If diploid spores are a rare event for a plant, then selfing is no better than outcrossing in the path towards polyploid offspring, since the process of generating a polyploid will most likely require a "triploid bridge".

The data above show that a high frequency of progeny produced by self-fertilization in diploid hybrids are tetraploid, suggesting that the hybrids are producing a high frequency of diploid spores (and gametophytes and gametes). A high frequency of hybrid production of diploid spores can also explain why most backcrosses from the diploid hybrids to the normal-meiosis diploid parents result in triploid progeny. By contrast, the non-hybrid plants do not appear to be producing polyploids at a high frequency (and thus diploid spores appear to not be common). This suggests that hybridity might, by itself, contribute to meiotic abnormalities.

The polyploid offspring of diploid hybrids are allopolyploids, while the polyploid offspring from non-hybrids would be autopolyploids. Selfing would thus appear to only help in producing allopolyploids (which might be expected to maintain their parent's trait of selfing), thereby leading to Stebbins' observation that selfing polyploids are commonly observed to be allopolyploids. If diploid spores are rare for nonhybrid, diploid plants, then selfing is not expected to assist in the formation of autopolyploids.

2. i) Intragametophytic selfing (IGS) can be estimated from genetic markers examined in sporophytes, as long as heterozygotes can be distinguished from homozygotes. Allozyme variation has this property (co-dominance) where both alleles are detectable in a heterozygote. The estimate of the IGS rate is based on examining sporophyte genotypes for multiple loci and looking for heterozygosity at any locus. IGS is the proportion of sporophytes that are homozygous at all loci examined.

ii) It is not possible to look for heterozygosity at all loci in the genome, and some of the sporophytes that are homozygous at the loci examined may be heterozygous at loci that were not examined. It’s also possible for crossing between gametophytes to result in homozygous individuals (if the two gametophytes had the same alleles). Consequently, the IGS rate estimated in this fashion is biased upwards (overestimates the amount of IGS). (Less likely - if duplicated loci (isozymes) with no variation (homozygous) are mistaken for allozyme variation at a single locus, the amount of heterozygosity may be overestimated and the IGS will consequently be underestimated).

If the IGS estimate is based on mature sporophytes, then the sporophytes that might have resulted from IGS may have been lost from the population due to poor survival (i.e. natural selection), and the IGS estimated from mature sporophytes is thus a biased underestimate (downwards bias) of the amount of IGS that happened at the time of fertilization.

iii) In these populations, the single observed genotype must be heterozygous at one or more loci (or else the IGS rate would be 1.0). Having all individuals share a single, heterozygous genotype either implies that reproduction is through asexual reproduction (most likely due to clonal spread through vegetative growth), or if sexual reproduction is occurring, natural selection is so extreme that all non-heterozygous sporophytes are eliminated from the population before they are large enough to be sampled for the analysis. Even if the replication of the genotype has occurred by asexual reproduction (vegetative spread), the heterozygous genotype, itself, must have arisen form a mating event between gametphytes, so it could not be the product of a single spore dispersal followed by IGS.

3. The authors of the article did not provide a specific answer to this question. Patterns such as this can be explained by factors that contribute to hybrid formation and/or to hybrid persistence once formed. Hawaii might differ because it is more tropical (closer to the equator), because of the geographic structure of the islands, because it is a relatively young flora, because it was not as disturbed by recent climate change, or because it is isolated relative to the continental floras.

(Formation)

Geography – If most of the reproductive isolation is provided by pre-mating barriers, there may be few opportunities for hybrids to form. In an area that is a collection of small islands, most species diversity occurs between islands (allopatry) rather than within islands. The pre-mating geographic barriers give related species few opportunities to hybridize. Alternatively, speciation that is occurring within islands (sympatric) is unlikely to result in new species without the primary evolution of pre-mating barriers (through indirect selection or through reinforcement), so there may be fewer opportunities for hybridization once species are formed.

Isolation – Hawaii may have a lower incidence of outcrossing taxa (a trait which the authors found to be associated with the incidence of hybridization). It could be expected that fewer outcrossing taxa are likely to make it to Hawaii -- islands are most likely to be colonized by self-fertilizing taxa because of their ability to establish a population with few (or one) plant.

Age – Hawaii has a young geologic age for its flora -- hybrid accumulation may be a consequence of the age of a region, with Hawaii's recent origin providing less time for hybrid accumulation. Alternately, if hybridization is characteristic of recent disturbance, the northern floras were heavily disturbed by the ice age that ended ~12,000 years ago, so they may show higher hybridization that results from new opportunities for gene flow for taxa that were separated during the ice age.

(Persistence)

Tropical - Hybrids are generally more frequent as you move away from the equator, and Hawaii is closer to the equator than the other floras. It may be that stronger biotic selection occurs in tropical and sub-tropical areas like Hawaii -- strong biotic selection may provide less forgiving conditions for the persistence of hybrid taxa if their fitness suffers. Alternately, the harsher abiotic conditions of the more northern floras might provide conditions that are more favorable to hybrids when they have improved fitness over their parents.

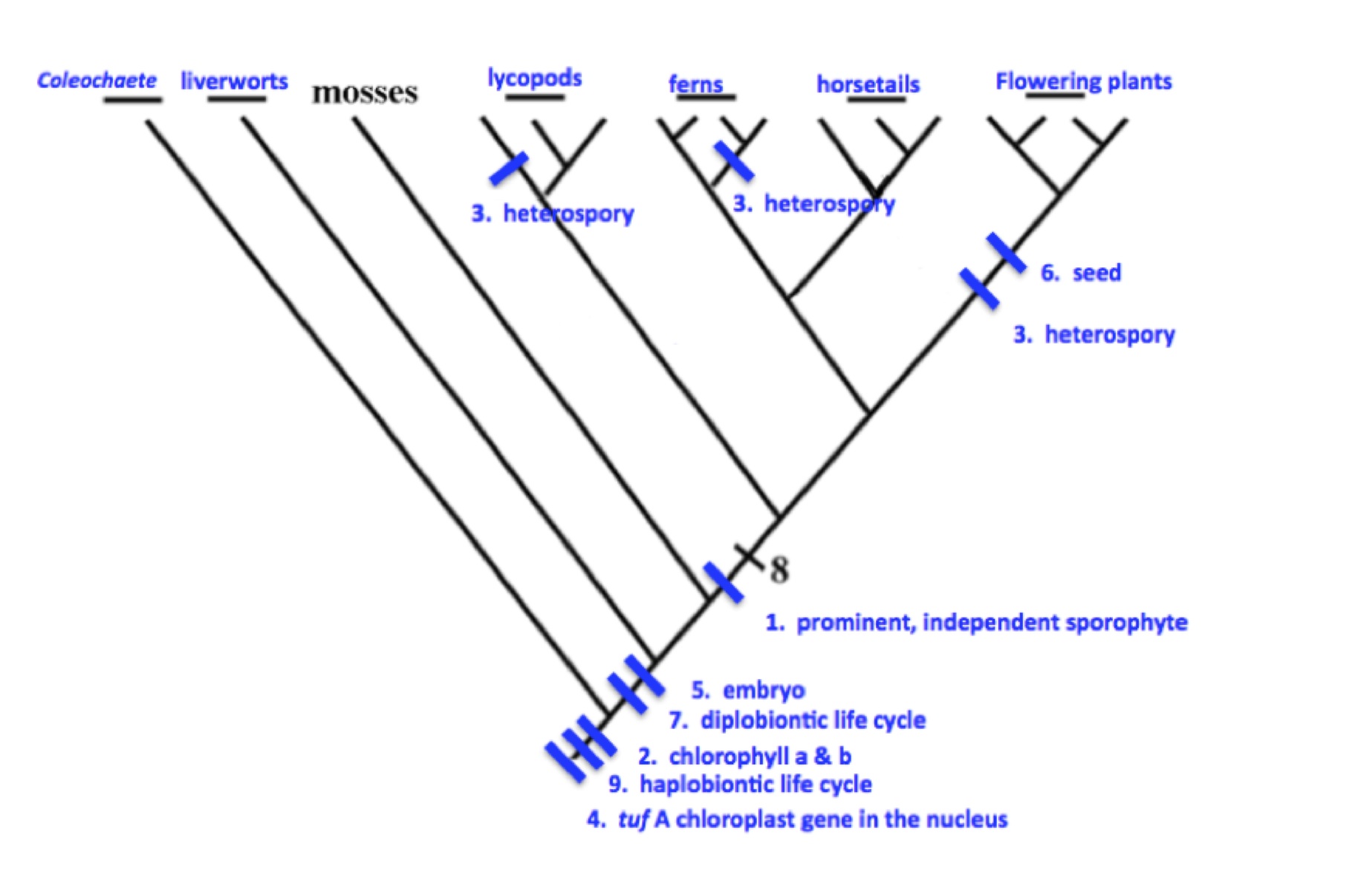

4. Both Charophycean algae and nonvascular plants utilize motile sperm in order for fertilization to take place. The motility of sperm through an aqueous medium is much easier for the algae in an aquatic environment than it is for the nonvascular plants in a terrestrial environment, where sexual reproduction is dependent on the availability of free water in the terrestrial environment.

Charophycean algae have zygotic meiosis when they produce spores, so typically only four haploid spores will result from meiosis. Nonvascular plants have added a mutlicellular sporophyte stage that results from mitotic division of the diploid zygote, so consequently more diploid "spore mother cells" are available to divide meiotically and thus many more haploid spores can be produced.

Interpolating (adding) a diploid sporophyte (diplobiontic life cycle) into the algal (haplobiontic) life cycle can be seen as an advantage that allows rare events (successful sperm transport and fertilization) to result in more meiotic products (spores) that initiate the next stage (haploid gametophyte) of the life cycle. Spores are also an especially important stage of the life cycle of plants in a terrestrial environment because spores allow for dispersal through space and time and are resistant to desiccation, so being able to get more than four spores from a single fertilization event is especially advantageous in the terrestrial environment.

5. For a phylogenetic analysis, we would want to construct a phylogeny with diploid and polyploid taxa that occur in both northern and southern latitudes, and then examine how these traits "map" onto the phylogeny.. Molecular data, independent of these traits, might be a good choice for phylogeny reconstruction.

Once the phylogeny is estimated, the trait combinations for the terminal taxa (ploidy; geography) can be used to reconstruct the evolutionary changes on internal branches and nodes (the “ancestors” on the tree), using the principle of parsimony (minimizing homoplastic changes). Once the changes in ploidy and latitude are mapped onto the phylogeny, by inspection it will be possible to determine how many times ploidy changes arose within clades prior to latitude shifts (before moving north, so polyploidy causes the northern success), and how many times polyploidy came after latitude shifts (high latitude causes polyploidy.

6. For the older interpretation (Fig 2a), the primary mode of speciation is polyploidy (shaded box), which would result in polyploid gene expression. Once formed, each lineage would undergo a process of gene silencing over the long period of lineage persistence (up to the present), which would lead to the current pattern of high chromosome counts and diploid gene expression.

Given Schneider et al.’s phylogeny, one (or both) of the assumptions underlying the older view must be incorrect.

One possibility is that polyploid speciation was a feature only of ancient diversification in the ferns, providing the time since then that is thought to be necessary for gene silencing, and the more recent diversification (shaded box) occurred within polyploid lineages without any further increases in ploidy and thus without adding back polyploid gene expression.

A second possibility is that the more recent diversification did involve polyploid speciation, but that gene silencing happened very rapidly in the short time since those speciation events. This would mean that gene silencing might be a much more rapid process than was previously thought to be the case.

7. Tempo in this case refers to the speed of the speciation process, while mode refers to the geographic circumstances of the populations that are speciating. The data on pollinator preferences show that for a trait that is affected primarily by a single locus, the phenotypic differences can have a very pronounced consequence for pollinator visitation rates and therefore for pre-mating reproductive isolation. A major gene locus that provides reproductive isolation could provide for a very rapid evolutionary divergence leading to speciation. Genes of major effect that lead to rapid divergence are an important element of the sympatric geographic mode, so this data could support a model of sympatric speciation. Rapid changes of this sort could also arise in allopatric populations, however, so the allopatric mode of speciation is not precluded. These data show primarily an effect of yup on insect visitation, so the single locus is unlikely, on its own, to eliminate visitation by hummingbirds to all genotypes. Reproductive isolation for sympatric populations might therefore require additional genetic changes (and longer time) to lead to hummingbirds limiting visitation to the “M. lewisii” plants with a yup L allele, so the sympatric explanation is probably less likely than an allopatric scenario based on these data for the yup locus.

8.