Hive Behavior in Honey Bees

James Holland and Theresa Steele

Biology 342

Drones

A drone bee on the comb. Image from ntsu.edu

Development:

Drones, the male bee caste, are born from haploid eggs laid by queens. Though a small number of workers in a hive are capable of laying haploid eggs, under normal conditions, only around 0.1% of a colony’s drones will be worker’s sons (Barron 2002). Like queens, once hatched, drones must continue to develop, consuming brood food for the protein and fat needed to develop a hard cuticle and grow reproductive organs (Winston 200). Once fully grown, drones serve little use within the colony -- drones produced in fall when there is no queen mating, or in times of scarcity, are often driven from the colony -- and spend most of their lives learning to fly, and traveling to and from mating sites where they will later reproduce with a queen (Winston 204). Drones, who use their brains primarily to find and memorize the location of mating sites, have been shown to respond less to aversive conditioning than their worker counterparts, performing around chance at avoiding a footshock (Dinges 2013).

Production:

Production of drone comb, the large wax cells in the nest in which drones are raised from eggs, is tightly regulated by a colony (Winston 200). The construction of drone comb is decreased when workers have tactile access to extant drone comb, and increased when they do not -- although hives will vary in the amount of comb the workers will construct (Pratt 1998). This potentially functions as a method of reproductive feedback, stabilizing the production of males at a level the hive can support, while also ensuring the hive will produce enough males to have a good chance of fertilizing a queen. Workers have also been shown to preferentially accept larger drones into the hive, but also direct more feeding and grooming behavior toward smaller drones (Goins 2013), likely as a mechanism to improve the hive’s overall reproductive success by producing more fit males.

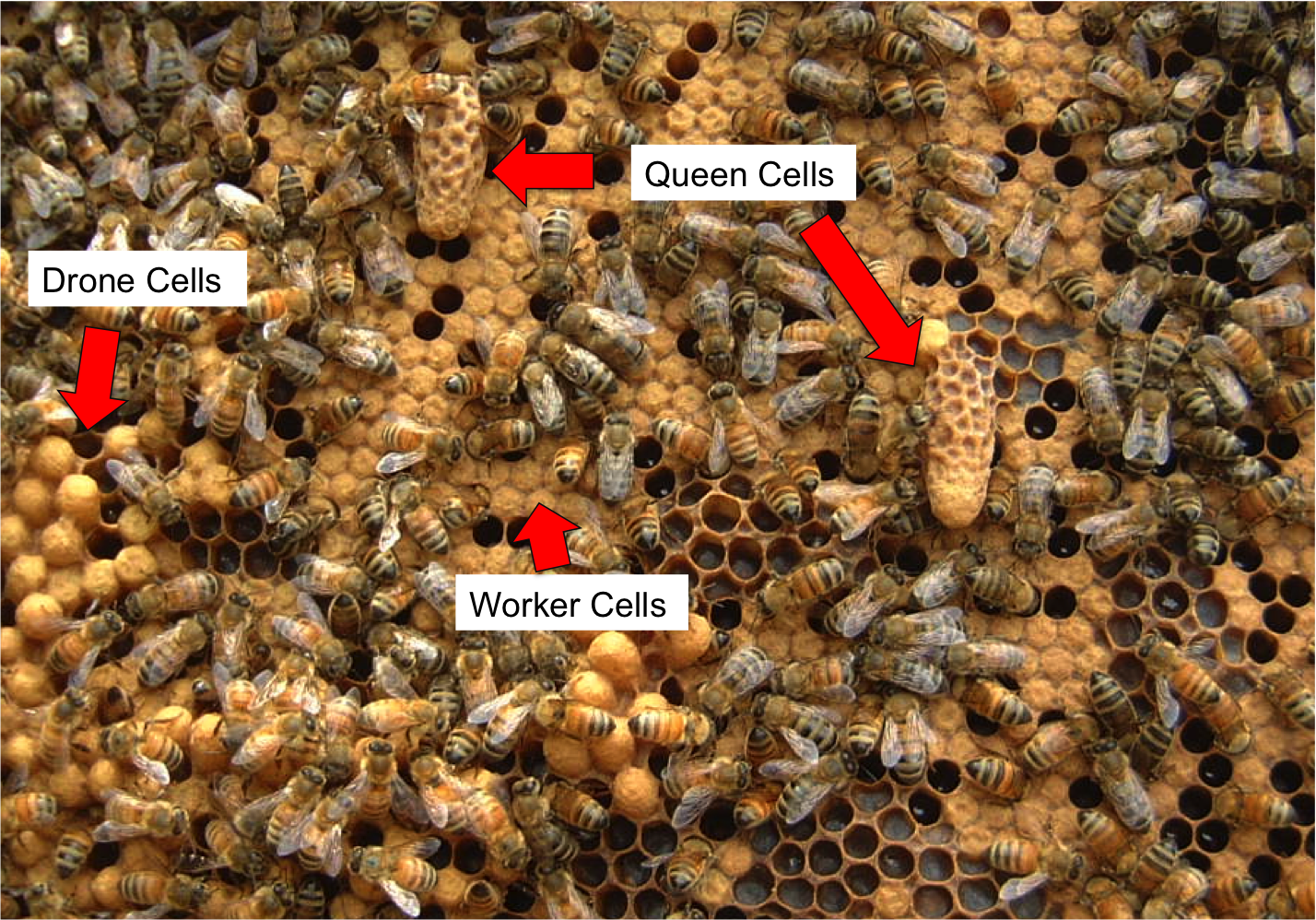

Types of brood comb within the hive, labelled by the caste it is used to produce. Image from bee informed.

Mating Behavior:

A queen and a drone mating. Image from coxshoney.com

During the spring, mature drones and virgin queens gather in aerial congregation areas, where the queens will fly through a cloud of drones, some of whom will mount and copulate with her (Wanner 2007). This copulatory act is “rapid and spectacular, with the drones literally exploding their semen into the genital orifice of the queen” (Winston 207), after which, the drone will die. In order to locate these mating sites, drones have specialized antennae and olfactory lobes for detecting 9-oxo-2-decenoic acid, a component of Queen Mandibular Pheromone thought to serve as a long distance signal for drones, which binds to a receptor known as AmOr11 (Wanner 2007). The structure of this mating gathering is evolutionarily significant -- because drones from multiple hives congregate with virgin queens from multiple hives, a colony can enhance their reproductive success by having more drones present at a congregation, to out compete drones from other hives for access to as many queens as possible. However, inbreeding can decrease a hive’s productivity and fitness (Mattilla 2007), and cause larval fatalities for as many as 50% of a queen’s offspring, in extreme cases (Winston) (see Hive Dynamics for more information). Consequently, a hive’s production of males is a process influenced by complex pressures.