IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 91, No. 3: September 2012

Reediana

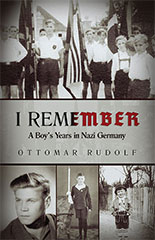

I Remember: A Boy’s Years in Nazi Germany (Inkwater Press, 2012)

By Ottomar Rudolf [German 1963–98]

Reviewed by Angie Jabine ’79

Ottomar Rudolf, emeritus professor of German and a tireless ambassador for the humanistic traditions of Germany, wrote this brief memoir to explain for posterity how it could be that he once belonged to the Hitler Youth and fought for the Nazis. He began the book in 1983, the 50th anniversary of Hitler’s rise to power, but notes that a new generation of fanatics, this time the radical jihadists, has given fresh urgency to his account of a boyhood “sacrificed to an evil philosophy.”

Rudolf briskly sets the historical stage, tracing the rise of Nazism to the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, “which we schoolchildren were taught to call Versailles Diktat, the Dictate of Versailles.” With an economy in tatters, conditions were ripe for extremism, and the generals of Germany’s standing army soon swore their allegiance not to the constitution but to Adolf Hitler. By 1935, when the Nuremburg laws codified anti-Semitism, Rudolf was six. By the time he was nine, membership in the Hitler Youth would be mandatory.

Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels orchestrated every aspect of German Kultur. Songs and movies extolling Nazi “martyrs” such as Horst Wessel “were the cultural icons of our lives.” Rudolf and his friends were enthralled by Hitlerjunge Quex, the story of a working-class Berlin teenager who joins the Hitler Youth but is murdered by Communists. “The film appealed to us because the boys belonging to the Hitler Youth were clean-cut boys, living a healthy life, camping, talking about the future of Germany, while the Communists smoked, listened to hit songs, had girls, were rowdies . . . We were all influenced by it.” (Watch Hitlerjunge Quex.)

As Rudolf relates his exploits as a 16-year-old tank gunner, it’s easy to picture the young extravert who looked just like the boys in the German war posters, and who idolized Field Marshal Rommel, the Desert Fox. In 148 pages, the narrative whipsaws between the starry-eyed teenager and the cultural historian who recoils at his own memories. He is so sparing with personal details that we never even learn his family members’ names—not the eldest brother who went down with his Messerschmitt 109, not the aunt who was killed in the firebombing of his beloved Ulm. The names he chooses to share are those of the few brave Germans who risked everything to defy the Nazis.

Further reading

“Ottomar’s Odyssey” [Reed, Autumn 2009].

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago