IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 94, No. 4: December 2015

A Life in Counterpoint

Photo by Robert Delahanty

Musician Jan DeWeese ’71 transforms solo to duet through his art and teaching.

By Laurie Lindquist

Photo by Robert Delahanty

The sky opened up that night and the rain came down in torrents, transforming sidewalks into rivulets and street corners into lakes. But nothing could dampen the spirit of those who gathered in a southeast Portland garage to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day. They arrived by scores and packed in tight, nursing cups of stout, snacking on plates of potluck, and craning their necks to listen to the music: a three-hour program orchestrated by the man who seems to have taught practically every banjo player in Portland—Jan DeWeese.

Over a span of more than 40 years, Jan has introduced hundreds of students to the joy and mystery of the banjo, mandolin, Irish flute, tin whistle, and the bodhran. But if you watch him dashing around on stage—introducing performers, tuning instruments, and plucking melodies—it’s clear that he is more than an instructor. He is a friend, mentor, and performer. He is also an artist who has spent his career wrestling with a profound dilemma.

![]()

Jan and siblings Cathie DeWeese-Parkinson ’69, MAT ’70, Gretchen, Tina, and Josh were raised in Bozeman, Montana, in a home dedicated to the arts. Their father, Bob, who taught at Montana State College, and their mother, Gennie, achieved notoriety for their work as abstract painters. “They believed that artistic freedom was an innate human freedom, and thus innately good for a just society,” says Jan.

Insulated from the cultural restrictions in that place, the children flourished in a virtual religion of creativity. “We ran wild in the hills at the edge of town and danced through the night to the drummers at the Crow Fair outside Billings.”

Jan took piano lessons, stretching his little hands into Bartók and Kabalefsky, before disappearing into the clarinet. Some of his first privileges were playing Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with the Montana State University Orchestra and scoring a superior at the state competition with Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet.

Cathie inspired Jan’s academic leanings, and he joined her at Reed after two years at Whitman College. “She tuned the DeWeese creativity toward social and political issues,” says Jan, who came to the college in 1968, when Cathie, her friend Ron Herndon ’70, and other students took over Eliot Hall to demand a black studies program.

Watching this confrontation, and many others of the turbulent ’60s, aroused a fierce debate for Jan: Is a good artist by definition a good person? What is the artist’s obligation to society? What is the right way to balance ethics and aesthetics? One clue came out of a dream at that time. Jan was back in the wild Bozeman hills, climbing a barbed-wire fence—strung like a music staff—in counterpoint with his childhood friend Eric. “The dream was of melodies, playfully providing space and encouraging freedom for each other. Common simple kindness, as in kin and the German Kinder.”

At Reed, Jan studied with Catherine Halverson Palladino, first clarinetist in the Oregon Symphony, and fell under the spell of J.S. Bach’s keyboard suites, thanks to Prof. Fred Rothchild [music 1953–78]. In Bach, Jan sensed a deep ethical undercurrent, a beacon to a resolution of the great debate. “This exquisite counterpoint posed equity between voices.”

He did his thesis on Bach’s “French Suite in D Minor” with Prof. Herb Gladstone [music 1946-80] and wrote fugues with Czech composer Tomáš Svoboda—experiences that further immersed him in the syntax of this intoxicating language.

After graduating, Jan worked for Reed’s music department, teaching ear-training—Bach chorales, Hindemith pitch studies, Schenker structural analysis—three times a week in Winch Capehart. But this austere, crystalline intellectual pursuit was destined to be thrown off course—by a penny whistle.

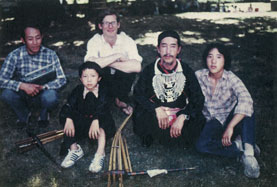

Jan (background, arms crossed) with kleng master Bua Xou Mua (wearing ceremonial necklace) and his son Lee (far right) at the CityFolk festival in 1981. Also pictured are Bua’s young kleng student and his father.

Jan was teaching in Winch when it happened. A group of underprivileged high-school students was visiting campus as part of the Learning Community orchestrated by Prof. Howard Waskow [English 1964–72]. “One of Howard’s kids, Sylvia Hackathorn, played an annoying little thing called the penny whistle, whose sounds drifted from the Commons right through my secure classical insulation,” Jan says.

The incident made him think again about the role of traditional musics in raising consciousness for social inequities. And at roughly the same time, another little instrument from afar landed in his hands. “On the mandolin, I could transform Bach keyboard soloness into duetness, into actual human dialogue with guitar friend Jeff Flowers.”

Propelled by the mandolin and the penny whistle, Jan found musical pathways linking folk traditions with the classical canon. Soon he and his mandolin student, Bill Bulick ’74, won a grant from the Metropolitan Arts Commission to form the Lost Arts Quartet, exploring Celtic and baroque styles. To further expand his musical vocabulary, Jan worked with Irish flutist Cathal McConnell, who came to Reed with Boys of the Lough, and studied African and Indian rhythmics with Collin Walcott, who performed at Reed with jazz trumpeter Don Cherry.

“Maybe the gap was closing, maybe the little peoples of the world, the victims of the empire and outcasts from the academy, were talking,” Jan recalls. “But the gap in our real world, the wound we’d inflicted on the innocent humans of Southeast Asia, was bleeding into our midst.”

Jan was hired by the Portland Mime Troupe to help refugee children arriving from the war to acclimate to their new home in Portland. “They joined in with my Ella Jenkins songs, in a proto-ensemble of bamboo flutes, xylophones, and gourd shakers.” One morning in 1980, at Boise-Eliot School, a shy Hmong refugee revealed to Jan that her father was also a musician. Soon, on a rainy night, in a dank Albina basement apartment, Jan met Bua Xou Mua and his family. He devoted the next decade of his life to the Hmong, whose improvised courtship songs tap the wellspring of counterpoint.

It was the start of a bold campaign, he says, “to help these delicate aesthetics survive the violent insult of their being here.” His ally in this gritty war was Mike Sweeney—one of the St. Patrick’s Day party hosts—soon to begin his career teaching anthropology at Lincoln High School. Mike procured funding for a Foxfire project, enabling hundreds of refugees to tell their stories through writing, radio, and photography, and Jan joined the team. They did fieldwork together for the National Endowment for the Arts’ CityFolk Festival and produced the six-week LincolnFest with more than 50 ethnic artists. Jan also did extensive multiethnic programing in elementary and middle schools, and wrote over a dozen grants to help Hmong and Lao musicians fund their teaching and instruments.

The whirlwind culminated in two fine victories: Bua became the first Asian American to win a National Heritage Fellowship from the NEA, which brought him, his son Lee, and Jan to Washington, D.C., where they met the preeminent musicologist Alan Lomax. “Lomax was stunned to recognize in Bua’s dance the link between Asian and European culture,” says Jan. The second victory was the NEA’s funding of Jan’s grant to begin the nation’s first apprenticeship program for refugees.

In the late ’80s, Jan’s musical career changed keys. He and his sweetheart, Robbin Isaacson, who had volunteered with Foxfire, married and welcomed their first child. And a new flowering of counterpoint inspired Jan’s work on the mandolin.

Jan and poet Kim Stafford combined melody and lyrics to record Wheel Made of Wind, and with violinist Harriet Wingard they recorded Pilgrim at Home. Along the way, Jan teamed with Brendan Fitzgerald and Teresa Baker for his Irish group, High Road. He formed the group CubaAche with Cuban refugee songwriter Roberto Gonzalez. Over the years, he has collaborated and recorded with dozens of musicians; his current songwriting friend is Chris Lydgate ’90. “The gift of helping each other far surpasses the lonely artist ego,” says Jan.

For his students, Jan serves as a messenger, bringing the wisdom of teachers from afar, channeling the structural elements of Celtic and African diasporas: Ireland to Appalachia, Mali to New Orleans, Galicia to Andalusia to Cuba, Congo to Cuba, Cuba to New Orleans. Reed figures fundamentally in his teaching: the structural approach to his Bach studies led to his teaching method, using both mathematical and stylistic elements, and his ear training provides the vocal tools for cementing these deep into his students’ musicianship. Jan says he is indebted to Reed students who have hauled their mandolins and banjos to his studio over these many years, to challenge him to hone all this into practices most useful to them. Katie Halloran ’15 has been one of his favorites.

“I took mandolin lessons with Jan all four years at Reed,” says Katie. “Jan is brilliant, and he’s got this remarkable ability to both pull high-level thinking out of his students and to meet students wherever they are. In my time with him, we covered everything from Bach to Bill Monroe, Irish music to Cuban music, and wide swaths of musical space in between. Along with all those different styles, he made me such a better musician—better at reading music, playing by ear, and thinking about the way a tune is constructed.”

“Music is the bridge for dialogue, commingling, and conversation on the side of good,” says Jan. But, in these times, music may not be powerful enough to bring about universal understanding, tolerance, or even peace. “Each of us has our own little piece of this puzzle, whether interpersonal or intercultural, so let your time on earth be filled with the rewards of creativity.”

Back at the party, the night has already fled into the wee morning hours when the band plays a stirring rendition of “O’Neill’s March” and takes up the banner song of the Irish Revolution of 1916. Next is traditional Ghanaian drumming by the ensemble led by Alex Addy, whose father, the late Obo Addy, was another of Jan’s teachers.

Then something extraordinary takes place. Responding to the infectious beat of the drums, Jan, on the penny whistle, and Doug Halsebo, on flute, get up on stage and bust out the reels and jigs. Fingers are flying and the crowd is on its feet. In this moment of cultural communion, the gap is closed. Another lesson, perhaps the greatest, in the art of counterpoint.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago