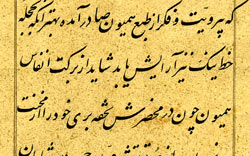

Text and Margins

The relationship between the text and margin is noteworthy when the paper used for the text and the paper used for the margin are different.

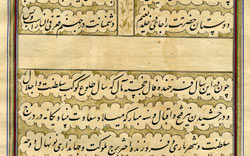

Margins are generally distinguished from the text with thin lines, called borders or jadval. Depending on the fineness of the manuscript or book, it could have multiple margins of varying colors. In fine manuscripts and albums, the paper for the text and the margin are usually of a differing type and color. Sometimes, the text of a book would be written on two pieces of thin paper that were glued together so that there would not be a shadow from the text on the other side of the page. For this reason, the paper used for the margin of the page would often be twice as thick as the paper used for the text. When a single page was used to write on both sides, attention would be paid to choosing a paper with similar thickness with the text in order to avoid wrinkles.

This is usually done when the margin is damaged. A type of paper would be selected for the margin similar in color and thickness to the paper used for the text. This way, the book would close flat, and there would not be wrinkles that would allow air to sieve through the pages.

This method of attaching a new margin would have been done with utmost care so that the paper of the text and of the margin were edge to edge and did not overlap. Usually, the touching edges of the papers were then hidden from view with colored borders. Because of the considerable degree of expertise and effort required to create these kinds of pages, this technique is found only in the finest of manuscripts or albums.

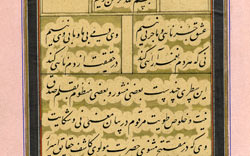

Symmetry

Symmetry is a common aspect of Islamicate arts, but at times slight varieties are embedded in seemingly symmetrical pieces, either for the sake of variety itself or because differing sizes of letters and words, which are out of the control of the artist, would disrupt the symmetry of the page. As such, despite their symmetrical appearance, there is rarely perfect symmetry in these works.

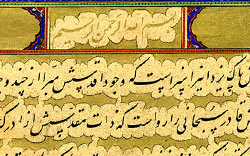

Tazhib

The art of illuminating manuscripts or the borders of calligraphic works is called tazhib. It is derived from the Arabic word for gold, dhahab, and it usually requires using gold. Tazhib, however, is not exclusively in gold. Other colors such as white, red, azure, etc. are also used. Tazhib drawings, which have a long history, are not naturalistic drawings; rather they are based on the imagination of the artist and are thus regarded as a distinct form of drawing.

Tazhib can be understood as a specific kind of gilding, but there are two ways in which gold was employed in the traditional art of bookmaking in Iran. In one, gold papers, which were extremely thin and brittle were used to cover all or part of the surface of a page. In the other, gold was used in liquid solutions for drawing or for writing, as in the case of tazhib. The following is the traditional method used for making gold solutions. A small piece of gold was placed between two pieces of leather, and hammered for a long time until a very thin layer of gold was produced. Then, the thin layer of gold was ground in a container with gum arabic or another type of adhesive material that produced a gold solution, which was then used as ink for writing, drawing, or creating borders.