Text and Margins

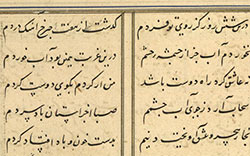

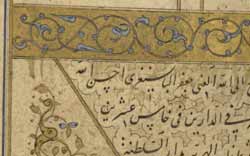

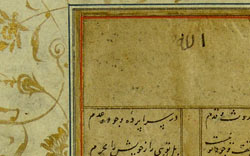

Margins are generally distinguished from the text with thin lines, called borders or jadval. Depending on the fineness of the manuscript or book, it could have multiple margins of varying colors. In fine manuscripts and albums, the paper for the text and the margin are usually of a differing type and color. Sometimes, the text of a book would be written on two pieces of thin paper that were glued together so that there would not be a shadow from the text on the other side of the page. For this reason, the paper used for the margin of the page would often be twice as thick as the paper used for the text.

Such a method was likely not used in this piece since the faint outline of the text and jadval from the other side of the paper can be seen, particularly at the bottom of the page.

Symmetry

Symmetry is a common aspect of Islamicate arts, but at times slight varieties are embedded in seemingly symmetrical pieces, either for the sake of variety itself or because differing sizes of letters and words, which are out of the control of the artist, would disrupt the symmetry of the page. As such, despite their symmetrical appearance, there is rarely perfect symmetry in these works.

In this piece, the symmetry of the hemistichs of the lines of poetry are mirrored in the symmetry of the lines used to frame them on the page.