Study Guide Household

Table of Contents

Furniture

Furniture is more than utilitarian: it reflects the self-image and values of the people who live amidst it. While Victorian America reveled in ornate and luxurious parlour furniture that displayed their “gentility,” Puritans hoped their clean plain furniture would reflect upon the purity of their souls. Even families with a “good social position” might not own any really fine furniture (Dow 33). These same families, however, might own valuable silver serving dishes (Dow 34). Wampanoag converts on the island followed this value system: for example, Naomai Ommaush left Zachary Hossueit, the minister, “six pewter dishes, and also seventeen pewter spoons” but does not mention any furniture beyond blankets in her will (Goddard & Bragdon I.55). Silver (or pewter) was associated with the church and hence may have been a more acceptable luxury. Even these pieces, however, were often simple or “plain” in style. As the eighteenth-century wore on, ornamentation increased. One of the finest sources we have for accessing the possessions of households are the inventories of estates made when people died (Dow 32). Records such as the one for George Athearn reveal what furnishings were deemed essential for whites on the Vineyard wealthy enough to attend Harvard.

Furniture is more than utilitarian: it reflects the self-image and values of the people who live amidst it. While Victorian America reveled in ornate and luxurious parlour furniture that displayed their “gentility,” Puritans hoped their clean plain furniture would reflect upon the purity of their souls. Even families with a “good social position” might not own any really fine furniture (Dow 33). These same families, however, might own valuable silver serving dishes (Dow 34). Wampanoag converts on the island followed this value system: for example, Naomai Ommaush left Zachary Hossueit, the minister, “six pewter dishes, and also seventeen pewter spoons” but does not mention any furniture beyond blankets in her will (Goddard & Bragdon I.55). Silver (or pewter) was associated with the church and hence may have been a more acceptable luxury. Even these pieces, however, were often simple or “plain” in style. As the eighteenth-century wore on, ornamentation increased. One of the finest sources we have for accessing the possessions of households are the inventories of estates made when people died (Dow 32). Records such as the one for George Athearn reveal what furnishings were deemed essential for whites on the Vineyard wealthy enough to attend Harvard.

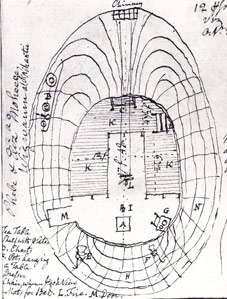

According to descriptions of wigwams from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Wampanoags furnished their houses with a combination of English and indigenous furniture. For example, Phebe and Eliza Mohege’s wigwam (right) drawn by Ezra Stiles in 1761 included a tea table, shelf with plates, chests, table chair, and dresser, as well as mats for bed and a traditional Algonquian fire place at the center of the house (Plane 2000: 107-08). Sleeping platforms covered in mats or skins were common in wigwams (Bragdon 106). The illustration of Jane Wamsley’s cottage from 1860 suggests that Wampanoag furnishings remained simple and unpretentious well into the Victorian era when other Americans valued ornamentation and ostentatiousness. Wamsley was a Baptist preacher (Silverman 429), but her simple cottage would have probably signified poverty not purity to the readers of Harper’s New Monthly.

Items Related to Furniture in the Archive

Fences < Previous | Next > Material Possessions