Sexual Cannibalism in Spiders

Dani Cardia and Charles Morse

Biology 342 Fall 08

Theory 2: Life History

Mechanism: Maturing at smaller size, and in poorer conditions, cannibalistic females have increased foraging vigor that turns mate into prey. Congeneric females often do not attack prey <15% their own size (Forster, 1992), yet small prey will be consumed when a female's condition is poor.

Nephila plumipes on her web, with male conspecific upon her back. Image courtesy of Frank's Photo Essays, Duke NUS Adaptive Value: There is adaptive value in female spiders having intensely aggressive behavior and eating anything in their path. Females of smaller size and poorer environmental advantage increase aggresiveness and decrease foraging selectivity (i.e. their mates become prey). This provides the adaptive value of nutrional gain, adjusting to the female's life history. The argument has been made that sexual cannibalism has no adaptive value. In a study of fishing spiders (Dolomedes), Arnqvist and Hendriksson (1997) found that the criteria previously cited as increaing female fitness were not enhanced through cannibalism. Female fitness can be measured as number of matings - or papal insertions - and body mass, from the final moult until egg production (Newman & Elgar 1991). In fishing spiders, food consumptions did not increase female fecundity, nor did the number of eggs differ between females who did cannibalize prior to laying and those who did not. Also, mating status of a female was not indicative of aggression (Arnqvist 1997). Rather, sexual cannibalism is seen to be related to earlier ontonogenic phases and genetic constraints. Juvenile growth and consumption determine adult size and fitness, and aggressive behavior is genetically constrained during ontogeny (Arnqvist 1997). Ontongeny: Schneider & Elgar (2002), working with Nephila plumipes, allowed cannibalistic females to kill their mates, but the bodies were removed before she could eat her male partner. Even without the nutritional benefit – a possible adaptive value to sexual cannibalism in the economic model – cannibalistic females gained significantly greater weight between maturation and oviposition, yet matured to a smaller size, than the non-cannibalistic females. The cannibalistic females also laid more eggs in their first clutch than those who did not eat their mate. This could support the nutrition-advantage hypothesis, as the benefits of cannibalism outweigh the costs for smaller females, yet the greater implication is a side-effect to poorer feeding conditions and lesser size with increased foraging vigor; females become less selective foragers (Schneider & Elgar, 2002). This is observed as an increase in aggression overall, and in particular in sexual cannibalism.

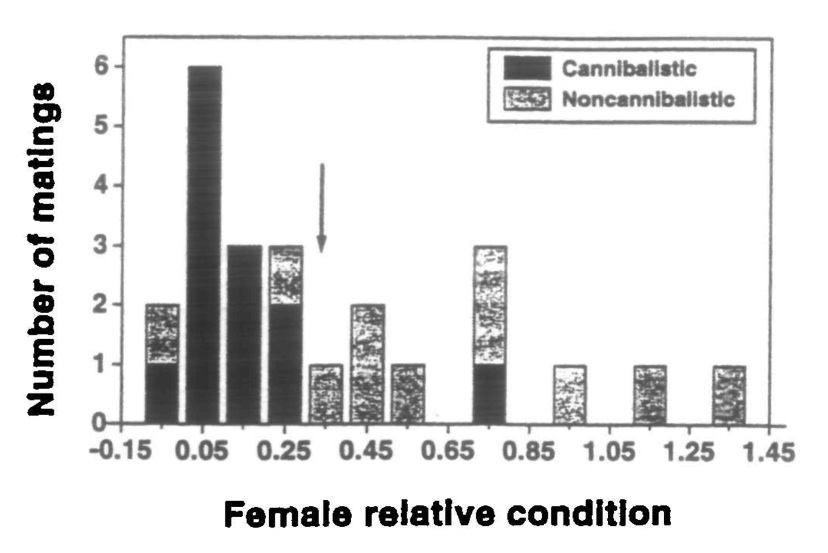

Figure 2. Relative condition of cannibalistic and noncannibalistic females from 24 field matings. Values on the x-axis represent midpoints of bins that encompass 0.1 units on the relative condition scale. A logistic regression analysis indentifies 0.31 (arrow) as the relative condition at which female bechavior is predicted to switch from cannibalistic to noncannibalistic. (Andrade 1998). The lack of a male counter-adaptation could be due to a low occurrence of mating opportunities. As long as reproductive costs remain low for the male in being cannibalized, the selection for a counter adaptation remains weak (Schneider & Elgar, 2002).

|