Mediating Persons and Publics

Final Projects from Anth 397 Media, Persons, Publics

The meteoric rise of new forms of digital data and social media in the past 20 years has generated, on the one hand, fantasies of utopic intimacy (the immediacy promised in a new "global village"), and on the other, moral panics about unprecedented estrangement (the hyper-mediation of virtual worlds and corporate or government "big data"). In anthropology professor Charlene Makley's course Media, Persons, Publics, we challenge this dichotomy of intimacy/immediacy versus estrangement/mediation by taking an anthropological approach to the question of human communication. Drawing on interdisciplinary debates in philosophy, linguistic anthropology, and media studies, we develop tools for understanding all communication as both mediated and material, grounded in embodied practices and technological infrastructures and situated in historical events. This in turn allows us to grasp how circulations of media forms and commodities participate in the creation of types of persons and publics across multiple scales of time and space. In a semester-long multimedia final project, proposed, planned and workshopped with creative consultants Tony Moreno, Joe Janiga and Ann Matshushima Chiu, students pivot from media consumers to media-makers, working in a variety of mediums and genres to illuminate or analyze particular persons' and publics' relationships with media. These projects illustrate the wide variety of genres and mediums students have worked in, as well as particularly creative modes of storytelling, rendering and editing. Working within specific standards, students' only stipulation for format was combining 5-7 pages of text with at least one other medium.

2023

Zoe Buhalis - Are We All Cyborgs?

Zine

Jozie Burns – e-artist

Zine

Emilie Kelly – Geese

Video

Essay

Emilie Kelly

Charlene Makley

ANTH 397: Media, Publics, Persons

5/9/2023

Geese can be a uniquely polarizing animal. Other wild animals like squirrels or racoons will try to avoid humans as much as possible, and domesticated animals like cats and dogs will be generally friendly to people, but geese are neither. They’re highly territorial animals whose preferred environment overlaps with human-centric spaces: golf courses, public parks, and the Reed college campus. Due to this, goose encounters are plentiful and can be difficult to maneuver out of… no one wants to get stuck between a goose and a hard place. Still, geese aren’t trying to be malicious towards humans. There just exists a common miscommunication between geese and people that can result in these kinds of goose-scuffles: geese want to be geese, people want to be people, and geese and people have different priorities. In some cases, people see geese as nothing but an inconvenience that needs to be dealt with. Other people will reach out to the geese and try to gain their trust like one would with a domesticated animal. The geese, on the other hand, seem to remain ambivalent to human efforts and are much more interested in their goose problems. While the mind of a goose may always be somewhat of a mystery to humans, the presence of geese and the attention they garner makes the existence of human-goose interactions integral to both the construct of human-centered spaces and the idea of what makes wild animals ‘wild’. GEESE wants to investigate the tension between geese and people and the impact that they have on each other, using Reed campus as a microcosm of the larger question of interspecies communication.

GEESE is a short film about the geese at Reed, using 20 interviews conducted with Reedies in the spring of 2023 as the basis for investigation. The interviews focus on establishing a baseline of goose opinion (“how do you feel about the geese on campus?”) then delve deeper into why the individual feels the way they do, whether other people’s opinions affect their own, how their opinion has changed through interacting with the geese, and finally whether they consider the geese to be a part of the Reed community. The interviews serve to both to collect data on how people think about geese, but also to measure how aware people are about the impact geese have on their lives. At Reed, not only did I have no issue goading people into talking about geese, they also had noticeably thought-provoking observations to share about geese. On average, Reedies demonstrated a love for open discussion and nuanced approach that could also broadly be used to categorize the personality of the school. “Determining the range of creatures we will communicate with is a political question, perhaps the political question” (Peters, 230), and Reedies pay attention to the geese. Geese are part of the circulation of discourse that, if we were to follow Habermas’ definition, constitute the public of Reed. Although the initial responses to geese could be split into two camps - pro-goose and anti-goose - the degree in which Reedies were interested in dissecting the nature of those answers felt both true to the spirit of Reed and respectful of the geese. To leave a discussion of geese at ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ goose is to only take into account a reactionary, human-centric viewpoint of geese. To truly understand how geese impact Reed, a more multifaceted, more cyborgian approach is warranted.

“What would the campus look like without geese?” Many Reedies responded by saying that it would feel emptier, have less personality, be less like Reed. These responses are indicative of a degree of awareness that Reedies have of how their identity as Reedies and the aura of the campus itself is, to some degree, dependent on the presence of geese - regardless of whether or

not geese and Reedies understand one another, Reedies and geese depend on one another in order to understand themselves as Reedies and geese. Donna Haraway’s model of cyborg politics, therefore, is a helpful model for this discussion. “Cyborg politics is the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication, against the one code that translates all meaning perfectly” (Haraway, 176). For Haraway, every individual can be seen as a cyborg, because every individual is also mutually constituted by their relationship with their environment, the tools and animals that surround them. For cyborgs, perfect communication is not necessary for understanding the world around you, because ‘perfect communication’ relies on the assumption that all knowledge must be directly translatable from one distinct individual party to another, instead of knowledge being based on gradually gaining experience from mutualistic relationships with one's environment. Perfect communication comes up once again in John Durham Peters’ writing as an idea he takes issue with, a sort of idealized, mystical form of communication where the absolute core of an idea has the ability to transfer from one party to another without losing any of its meaning or significance, “a meeting of the minds that would leave no remainder” (Peters, 16). For Haraway, perfect communication is a farce because the notion of a true individual is flawed. For Peters, perfect communication is unrealistic because the kind of pure telepathy it would require doesn’t take into account the barriers between minds, makes no distinction between one thought and another, and that is a version of existence so alien it’s not worth pursuing. In my mind, nothing interrupts the fantasy of perfect communication like a goose.

When you talk to the geese, the geese do not talk back. The geese will not move if they are on a path, because your feeble attempts to get them to move are not compelling for a goose. Even the joy that those who see the geese as entertainment derive from the presence of geese is

mainly due to the incomprehensibility of geese: “what are you doing there?”, “I like that they don’t talk back”, “I like when one of them honks at the other”. One cannot presume what a goose is thinking, and any attempts to do so just end in frustration. Geese cannot be approached as pets, because to do so is to anthropomorphize them to a degree where the human perspective (geese as cute birds) supersedes the animal’s (geese don’t care about being pets). Geese cannot be approached as pests, because once again the human perspective (geese are annoying) assumes too much about the nature of geese (geese don’t understand that they are annoying to humans). Geese don’t care about maintaining perfectly manicured lawns. Geese don’t care if they wake you up by honking. Geese don’t care that they’re blocking the road and you need to get to your appointment. They will not take up less space, and they will not be made to care. Geese just care about being geese, and try as one might, a person will never be a goose. All that geese leave us with is a constant reminder of this insurmountable abyss of communication between us and them, even as we share the same environment. What does it take then to communicate with a creature that, genuinely, has so little concern with how it is received? Why do they still capture the attention of Reedies, when we have no clue what they’re saying? What do we do when we hit the limits of rationalization?

In the process of fulfilling this project, I spent hours thinking about the geese, talking about the geese, and observing the geese. In the process, I didn’t feel necessarily closer to the geese, but I did grow to respect them, and I began to feel a certain kind of calmness from spending time around them. I realized that paying attention to geese doesn’t always mean paying attention to the geese: paying attention to geese can be about not paying attention to everything else. The priorities of modern life can sometimes feel artificially heightened, overwhelming, or disingenuine - we can become estranged from our work by objectifying it, thus objectifying

ourselves and our relationships with others and our environment. The advent of ‘wellness’ or ‘authenticity’ economies present one approach to the modern condition by selling back a person’s ‘true self’ or ‘peace-of-mind’ as a series of products targeting the idea of self-care. At my most cynical, I see the corporate wellness trends as a band-aid for a bullet-wound. The consumable self-care product aims to placate, but in return the product creates an additional layer of mediation between the individual and the outside world, creating a reliability on mediation-as-meditation that only feeds into more product to sell. The promise of meditation (not mediation), however, is one of experienced immediacy. A guided meditation will tell you to clear your mind of any other thoughts… but what is more effective in clearing your mind than an encounter with a goose?

I don’t see geese-as-a-state-of-mind replacing bath bombs any time soon, nor do I think that would be a good idea. The role that nature plays between people and the world isn’t one that an object can replace - in fact, that’s the whole point. It's exactly the lack of ability to communicate as one would with another human being that makes nature and animals so centering. There is a practical limit to the extent one can logic themselves out of situations without spiraling or burning out. Interactions between human and non-human entities often require putting away the distinctions of language and relying instead on instinct, and instinct requires full-body participation. It is like tuning an instrument: it must be done slowly, taking into consideration both the player, the instrument, and the area, listening for the harmonies to emerge. In a way, honing one’s instincts are the inverse of the labor-incentivized alienation Marx described. Interacting with geese connects us with geese, with the environment, and with ourselves.

Being on Reed campus, one is bound to see a goose. The campus wouldn’t be the same without them, either the cackling geese or the Canadian geese, the same way it wouldn’t be the same without the Portland rain or the noise from the weekly Balls. While the geese can sometimes feel like a burden when seen only as the ways in which they inconvenience people, those inconveniences, those miscommunications, are also a reminder of all the ways the world is full of unique and interesting things that will never fail to surprise you. On a campus filled with people so dedicated to exploring the world, coming together to give the geese the space they deserve is a pleasure and a point of pride.

Works Cited

Peters, John Durham, Introduction: the problem of communication, Speaking into the air: a history of the idea of communication, pp. 1-31, University of Chicago Press, 2000

Peters, John Durham, Machines, animals, and aliens: horizons of incommunicability, Speaking into the air: a history of the idea of communication, pp. 227-261, University of Chicago Press, 2000

Habermas, Jurgen, Introduction: preliminary demarcation of a type of bourgeois public sphere, The structural transformation of the public sphere, pp. 1-26, 251-256, MIT Press, 1989

Haraway, Donna J., A cyborg manifesto: science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century, Simians, cyborgs, and women: the reinvention of nature, pp. 149-181, 243-248, Routledge, London and New York, 1999

Marx, Karl, Estranged labor, Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844, pp. 69-84, Prometheus Books, 1988

Thor Madsen: Between Two Worlds

Video

Essay

Between Two Worlds:

Cosplayers as Mediums of Personhood and Social Connection

Thor Madsen

ANT 397: Media, Persons, and Publics

Prof. Char Makley

May 9, 2023

To better understand the medial experience and how cosplayers are perceived, this paper provides context to its associated video made up of interviews and photographic montages to observe how cosplayers act as mediums of social connection and self-discovery. The photos and interviews on the video montage associated with this article tell the story of why and how they cosplay, the challenges cosplayers encounter along the way, and how they navigate those challenges while still maintaining the immediacy cosplay has given them. Through video interviews, audio and visual captures of the environment where cosplayers perform, and text narration, we can get a sense of the experience through cosplayers' feelings about what they do.

When asked what they do, the cosplayers we very happy to discuss the amount of time and effort they put into becoming the character they will be performing—through costume, accessories (many of which are fantastically impractical “lethal” weapons), mannerisms and makeup (especially makeup). However, when asked about how they feel about what they do, each cosplayer invariably began with some variation of, “It’s fun!” Then, as they shared how it was fun, they began to share—as if then becoming cognizant of it—the importance of their role in mediating one world into another through their character. People they came into contact with were often drawn into the cosplayer’s performance. It is a shared sense of immediacy where the cosplayer’s presence expands from play to being engaged in their own development of ideas. Cosplay, at its essence, is about our personhood—what Donna Haraway would call the “serious play” of Cyborgs. (Haraway 1991, 149) Humans, beyond their selves, are extensions of and into their environment, becoming something else through it. In this case, that something else becomes embodied in a character that cosplayer sees something of themselves in—at least for the weekend.

Much of this story of immediation takes place where most cosplayers gather and first come out—a science fiction fantasy conference in Portland, OR. My approach, centered on feeling as an entryway, is partially framed by the “rough schematic” of Boyer’s triad of poetic, medial, and formal (Boyer 2007, 26), where cosplayers act as mediums of personhood and community through their co-option of corporate-owned paths of creation and modern-legal establishment of fantasy characters. The cosplayer embodies Agha’s concept of “mediatization” by imbuing a commodity product with an immediacy that forms a community. (Agha 2011, 171)

As I have proceeded on this path, most cosplayers have been willing to share with me, in a sometimes-profound way, why they do what they do and what happens to them and those around them when they perform it. Kate Bornstein would see these character performances as a kaleidoscope of fluidity, especially in her description of Disney-Pixar’s WALL•E and EVE. (Bornstein and Bornstein 2013, 81). From a more structured perspective, Diana Taylor would likely see cosplaying as a mixture of accepted “performative ” rituals (2016, 73) based on how cosplaying is done and “performance” (Taylor 2016, 13) when cosplayers take the stage to act out their characters in front of an intentional audience, place, and time. It is not surprising that underlying the impeccably stylized hair, makeup, costume, and affected mannerisms of a chosen fantasy character, cosplayers have more to say about connecting with themselves and others through their performance than they do about the character itself (although happy to go into detail).

Haraway might view cosplayers as a cyborg performance. Through their costume, mannerisms, and conveying the spirit of their character, they become a type of cyborg performing as mediums—"a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction.” (1991, 149) This could not be a more apt description of the cosplayer, meshing self with machine, whether corporeal or ethereal—in a display of extended self. (Many describe this extension as “me” but a cooler version. It is as if Haraway had just returned from a Comic-Con when writing this.

In agreement with Bornstein, Haraway might appreciate cosplay’s subversion of roles. Yet, she would likely also be alarmed at the corporate entanglement within many of these characters and how that can lead to a reinforcement of dominant norms. Yet again, I still think Haraway would appreciate the ironic potential of this model of performance that co-opts media characters directly in front of the studios sponsoring the event.

To address these challenges of cosplayer mediatization, the video gives examples of corporate ownership of these mediatized forms and the dilemmas cosplayers face amid a capitalist-dominated media universe where even their character is copywritten. In this way, cosplayers are Agha’s specific, mediatized connection between “commodity and communication” as they create immediacy among those who engage them in the performance. There is a brief clip of this in action where a cosplayer streams their character’s appearance and even movement at the “con,” surrounded by other cosplayers, through TikTok. This five-second image of multimodality (with unseen algorithmic hypermediation of targeted advertising and more streaming to follow her livestream) encapsulates the “homework” economy where “factory, home, and market are integrated.” (Haraway 1991, 166) Per Haraway, “cyborgs are the ether, quintessence” of this integration. (1991, 153) This ethereal quality of the cyborg and the example of the streaming cosplayer complicate Boellstorff’s interpretation of the cyborg “boundary figure” as incapable of attaching actual (physical) to virtual. (Boellstorff 2015, 138) Through this cosplayer (and as shared by interviewees), we can observe evidence of the mediatized actual extending, cyborgian, into the virtual and looping back into the actual as followers mimic and then seek out a corporate media venue—anime, manga, etc.—where they can consume the character in a more direct, monetized channel.

As Meyer found, this mediatization is critical for immediacy to the point where social connection and communities—like counterpublics—emerge, and all are intertwined. In fact, immediacy “depends on authorized mediation practices” (Meyer 2011, 27), and cosplayers mediate social connections and act as a collective authority on those practices. However, there is no central cosplaying authority—rather, cosplayers have historically and now, through social media platforms, dedicated their efforts to affecting mediation practices across a range of commitments to embodying or consuming the embodiment of the character. The video portrays examples of this intertwining through the care each cosplayer takes in, the exactitude with which they know their character, and a mutual understanding among them on performative behavior—especially in taking their character’s “stance.” (Madsen 2023, sc. 9:06) It follows that, as mediums, they are “hyper-apparent” (Meyer 2011, 34) in this process.

Two of the cosplayers, “Leah” and “Angela,” while interviewed in the comparative quiet of a Zoom call, give a reflective sense of being made hyper-apparent in the cosplaying universe. Both share insight into how they navigate and, for the former cosplayer, navigate the challenges, especially the mediatization, and homework, of cosplay. How did they maintain the immediacy (as cosplayers put it, the fun) created through their fantastical characters? I have found, (Ben Read et al. 2022), capitalized media platforms can be more effectively subverted, rather than resisted, for purposes other than intended based on a social presence in the physical space of cosplaying. Meanwhile, we can anticipate artificially intelligent, algorithmic social mediators will inevitably determine a pathway toward assuring mediatization of this other, more actual world-centered human connection and creation of immediacy. LaTour would see this process as demonstrating the greater “actant” network for accomplishing any network of activity. As fellow actants, humans as cosplayers in the actual world—as seen by the streaming cosplayer—will increasingly intertwine with algorithms in forming social connections and personhood.

For this reason, throughout the interviews, the focus has been on how cosplayers feel about why they do what they do. This route of inquiry helps weave out the personification of media properties outside the hold of media corporations. As one cosplayer said, “Instead of buying the action figure, you are the action figure.” Their experience invariably allows the cosplayer to explore in the moment of the interview the pathway between “it’s fun” to “I become the character,” and the people around them are drawn. Meanwhile, cosplayers, often living in a counterpublic, find their own “normal” in a unique place to define and grow their personhood.

The associated film will provide insight to scholars assessing the implications of commercialization, through media, on social connection and self. The cosplayers and creators portrayed share profoundly personal experiences in playing a central role as mediums of personhood and social connection. Cosplayer’s simultaneous co-option of and co-option by corporate media properties especially provides a robust framework for inquiry into the complicating factors of commercially hypermediated spaces. Here, cosplayers play a clear role in the “mediatization of mediation” while embodying the literal “mediatized figure of personhood” as described by Agha. (Agha 2011, 173)

More broadly, this is a story of the human arc of personhood for those who are drawn in by the exacting and fluid performances delivered by representatives of counterpublics. Cosplayers, beyond fans, precariously perform a central role of fandom itself. Their adeptness at “humour and serious play” (Haraway 1991, 149) makes cosplayers powerful cyborgs capable of forcing corporations, through the irony of the profit motive, to simultaneously rely on cosplayer adoration while the management of them as a unique brand remains elusive.

Ideally, and most importantly, the film is a story meant for the cosplayer and other performers outside the mainstream who are invited to participate in its creation and telling as an ongoing multimodal observation of the human at the center of the cyborg.

Bibliography

Agha, Asif. 2011. “Large and Small Scale Forms of Personhood.” Language & Communication 31 (3): 171–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2011.02.006.

Ben Read, David Isaak, Emma Holland, Josh Grgas, Emi Karydes, Soroa Lear, and Thor Madsen. 2022. “Let’s Be Disinterested Together: Social Media, Personhood, and Control.” Confluence XXVIII (1). https://www.confluence-aglsp.org/xxviii1_read.

Boellstorff, Tom. 2015. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. First new edition paperback. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Bornstein, Kate, and Kate Bornstein. 2013. My New Gender Workbook : A Step-by-Step Guide to Achieving World Peace through Gender Anarchy and Sex Positivity. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203109038.

Boyer, Dominic. 2007. Understanding Media: A Popular Philosophy. Paradigm 30. Chicago, Ill: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

Madsen, Thor, dir. 2023. Between Two Worlds: Cosplayers as Mediums of Personhood and Social Connection. Video, 4K, 60fps. Documentary.

Meyer, Birgit. 2011. “Mediation and Immediacy: Sensational Forms, Semiotic Ideologies and the Question of the Medium.” Social Anthropology 19 (1): 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2010.00137.x.

Taylor, Diana. 2016. Performance. Durham: Duke University Press.

Appendix: Interview Questions

What and How did you cosplay?

What theme(s) do (did) you cosplay in?

With whom did you cosplay?

Where?

How long did you cosplay?

Did you make your own costume, purchase, etc.?

Why did you cosplay?

Who was your favorite character and why?

Please describe your experience as you put on your costume…(and when you are fully in your costume and cosplaying).

How do you feel in each instance?

Effect of Cosplaying

How has cosplay affected you up to this day if at all)? Is there anything that it has taught you?

In what ways, if any, do you feel “as a cosplayer,” outside of actual cosplaying, today?

Oscar Pulliam – Censorship

Zine

Essay

The Paradox of Censorship: The Value and Implications of Censorship in Photography Oscar Pulliam – 9th May 2023

Table of Contents

Introduction

Contextualizing Images

Definiton of Spaces and Publics

Methodology Of Censorship

Conclusion

Introduction

Why is there information deemed by some metric too sensitive, offensive, or even dangerous for public consumption? This was not a question I expected to need answer as a photographer, however the content of my work forces me to consider it. In a world where images and the information they contain shapes perceptions throughout the public sphere, censorship has rapidly become a compelling subject of anthropological analysis. As the role of photos evolves, the dynamics of their influence become an increasingly vital component to understanding communication within publics. Images are one of the most universally understood forms of communication in society. For that reason, I love photography. However, this accessibility comes with responsibility to both accurately depict the subject of your photo and to consider the potential outcomes of distributing an image.

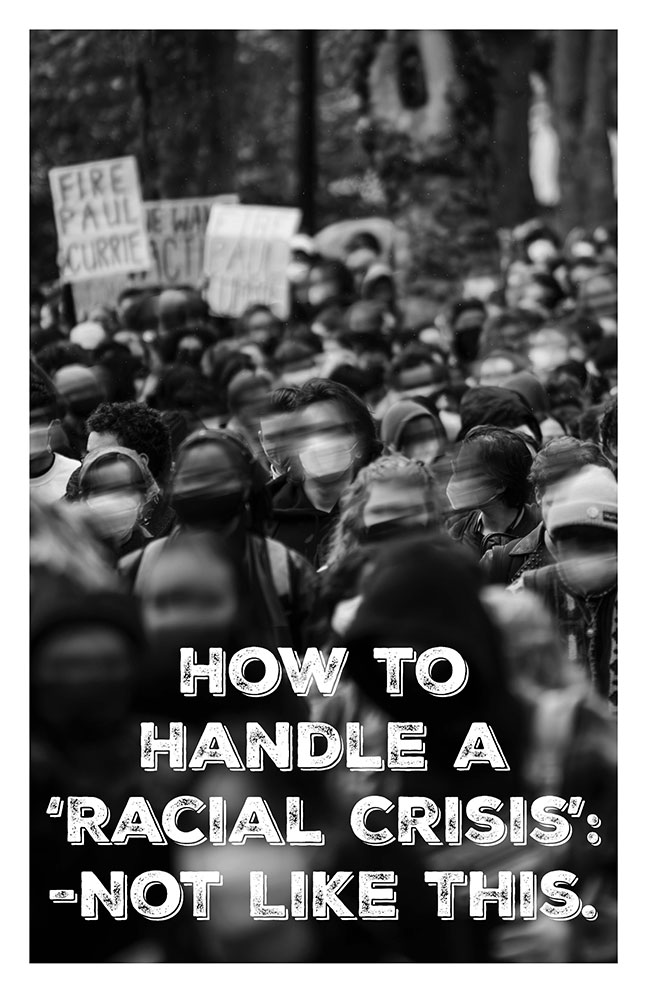

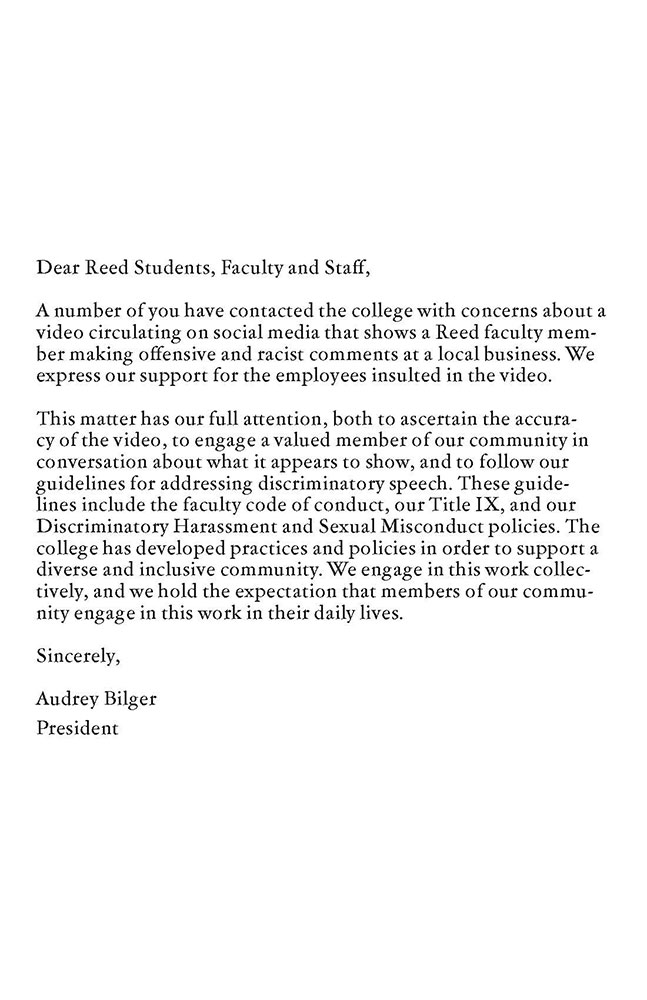

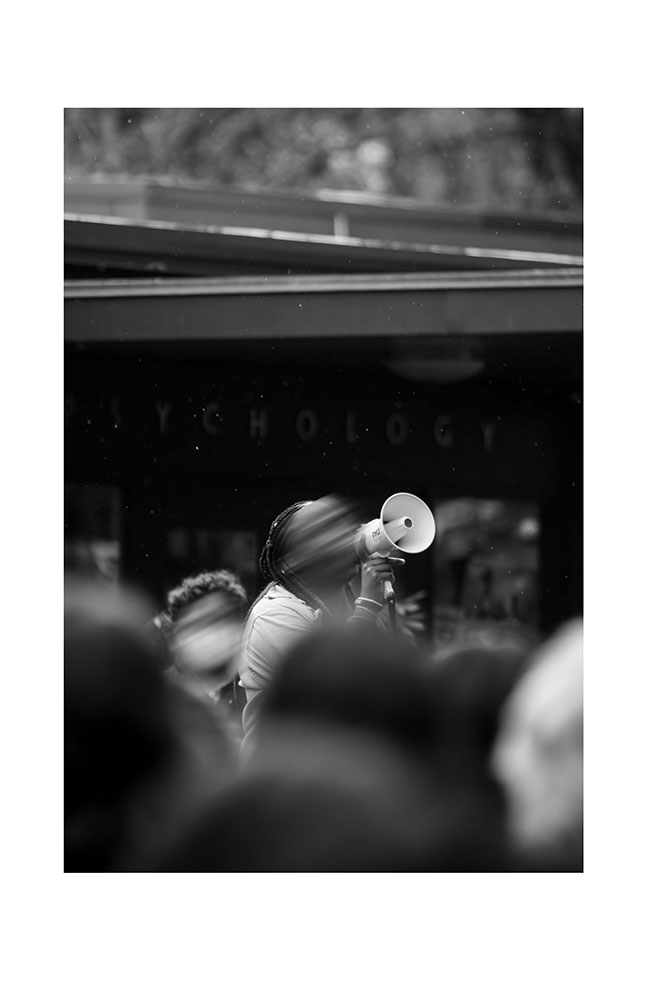

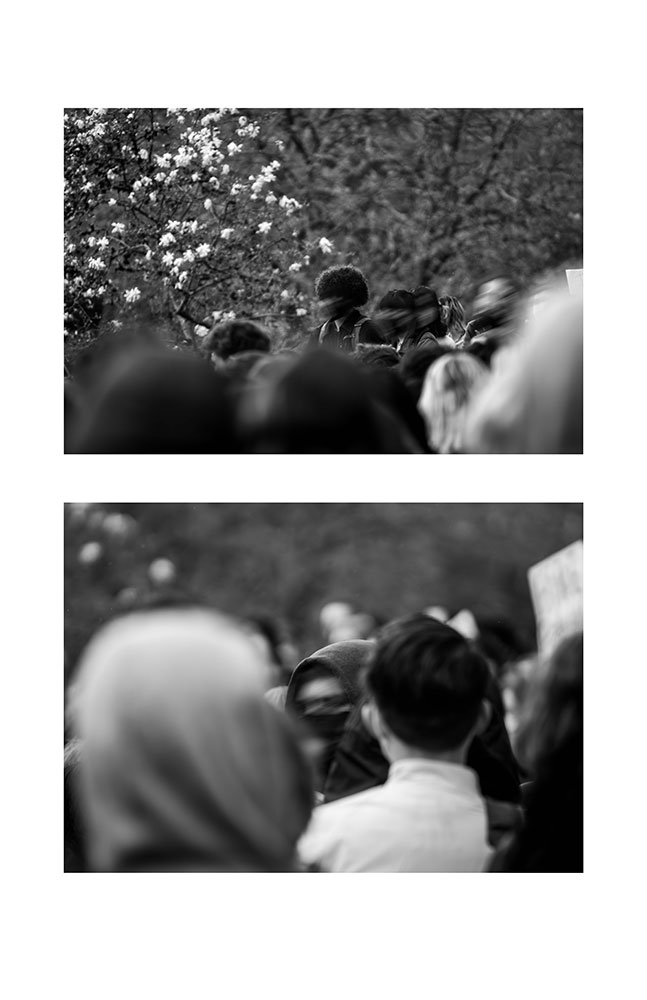

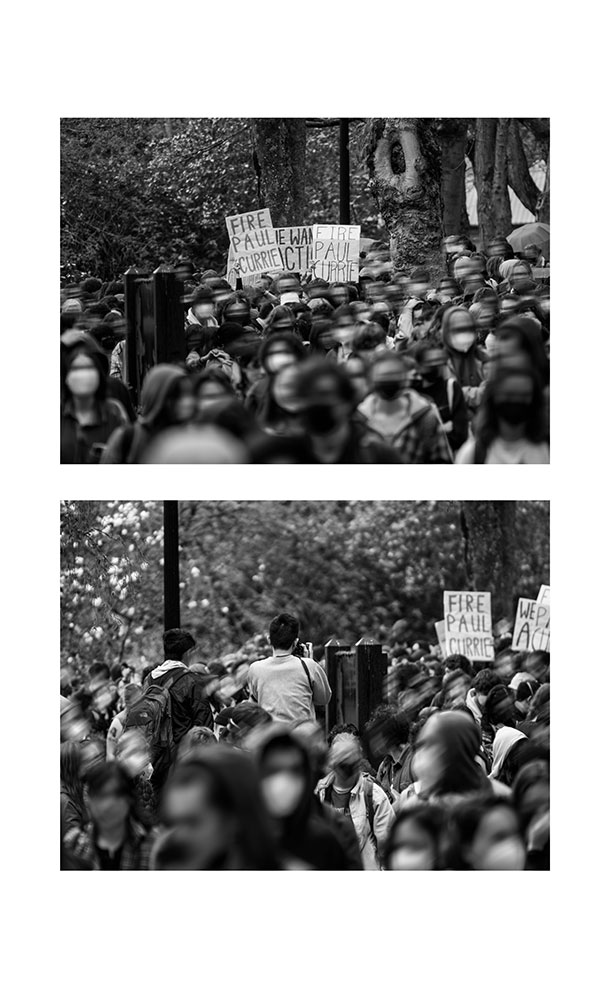

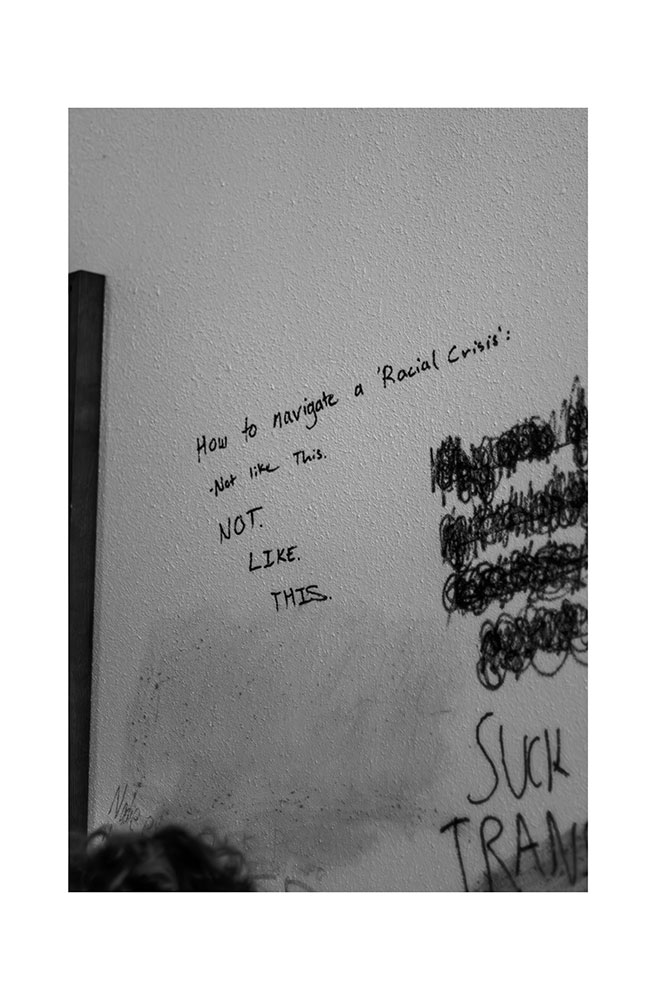

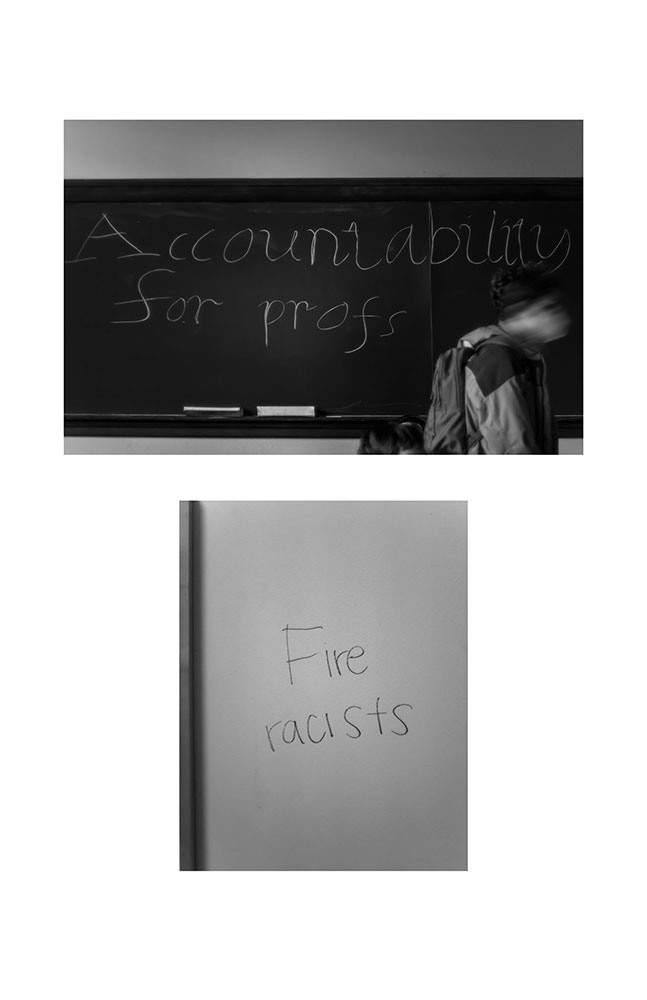

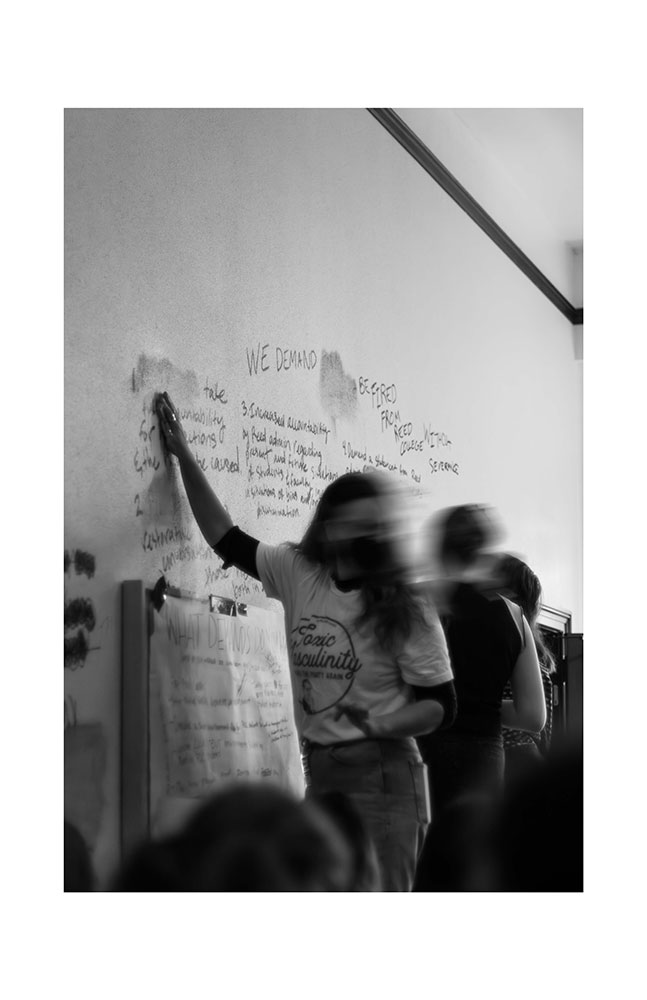

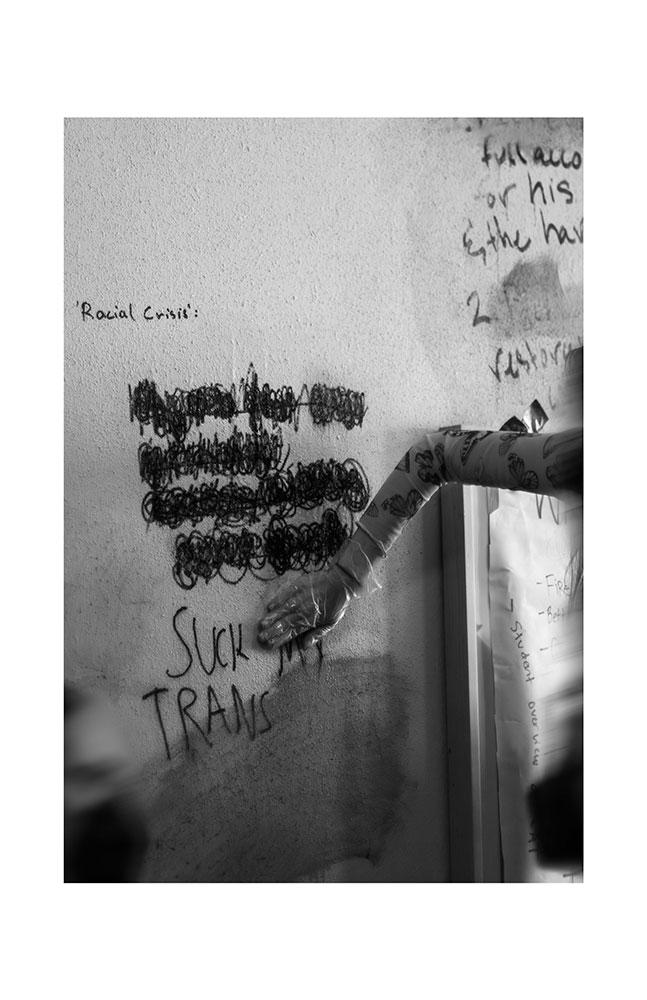

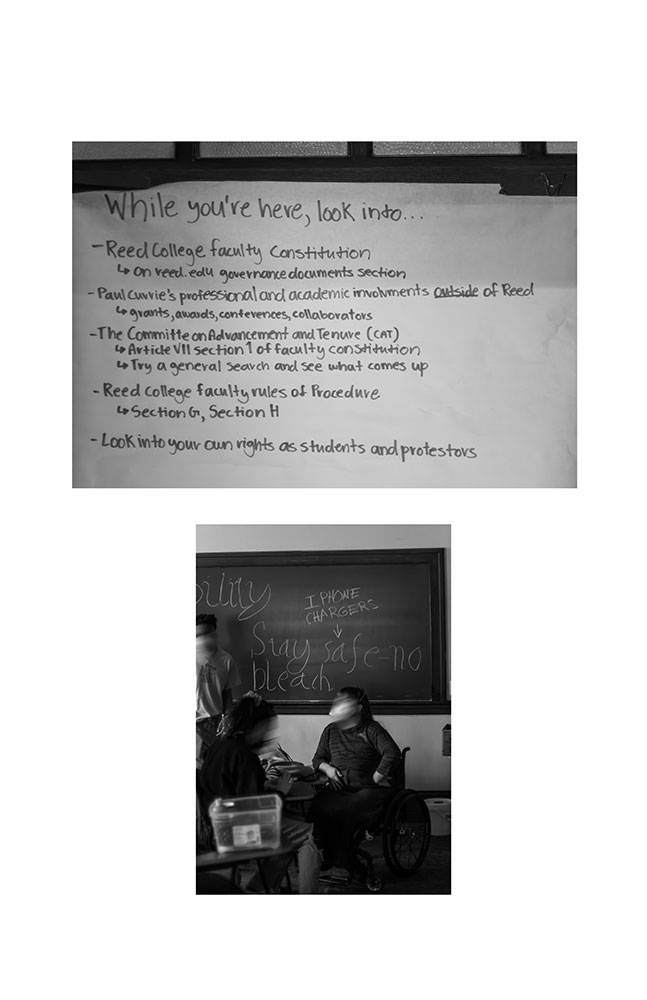

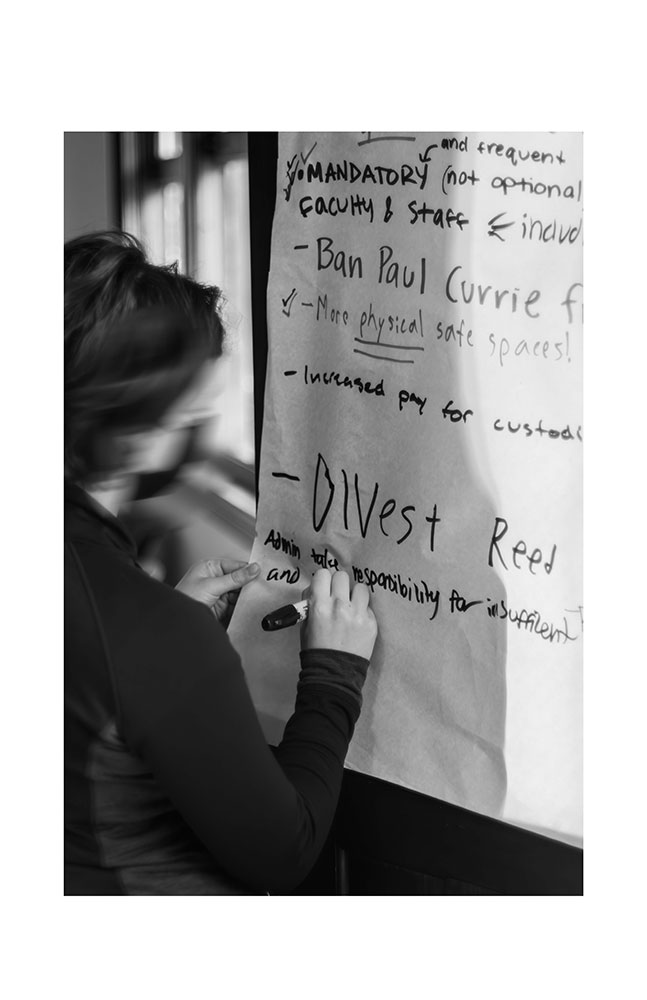

My aim is to analyze the role of censorship, specifically within the constraint of documentary work. The primary example for dissection will be my own zine, “How to Navigate a ‘Racial Crisis’: -Not Like This.” The zine is intended to record the perspectives and viewpoints of the Reed College student body regarding the events following Paul Currie’s racist, xenophobic statements. Therefore, a key issue in ensuring this goal is achieved is to ensure that no extraneous influences contaminate the student body’s message. My goal in this paper is thus to explain the process and decisions which led me to the final version of the zine, and to explore the multitude of relationships, perspectives, and ideas inherently included in modern media, especially those involving photography and images.

Contextualizing Images

The essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Technological Reproducibility” by Walter Benjamin is significant in that it is one of the earlier commentaries on photography and its role as an art form. The piece argues that photography fundamentally changes our understanding of art and the role of the artist (Benjamin 102, 103). Prior to the advent of photography, art was primarily valued for its aura–its unique presence in time and space. However, photography's ability to reproduce images on a mass scale disrupts this aura, leading to the universalization and commodification of art in capitalist society (Benjamin 104). This new form of documenting the world, Benjamin suggests, has important implications in the context of politics and activism due to the fact that it can challenge dominant narratives and power structures. Additionally, Benjamin claims that photography has the potential to be oppressive, depending on how it is used (Benjamin 104, 105). He notes that photography can be used to create propaganda and reinforce oppressive power structures, but it can also be used to document and resist those structures. In the context of the zine, these concepts highlight the ways in which photography sets itself apart from other ways in which the protest is documented (in The Quest, for example). It forces me to consider the power an image holds in comparison to other representations of the message.

In order to better understand how this relationship is shaped, consider Bruno Latour's idea of hybrid collectives is another perspective to consider in this context. According to Latour technologies–such as cameras–are not separate from humans. Rather, they are directly connected to humans through a dynamic relationship (Latour 174, 177, 178). In the context of photography, we can see how the camera is not simply an object, but an active participant in shaping the image that is produced. The camera embodies certain values and assumptions about how the world should be represented, such as the conventions of framing, composition, and lighting. The photographer, in turn, works with the camera to produce a specific image that reflects their own perspective and intentions. It is not a static or fixed medium, as the choices made by the photographer directly impact how messages are conveyed.

Consider, for example, my choice of lenses for this project. The outdoor photos were made using a Rokkor-X 200mm 2.8, a super-telephoto lens from the 1980’s. The individual characteristics of this lens are numerous, however the most significant is its focal length of 200mm. The lens is incredibly tight, designed to capture moments from a distance, and the photos it makes reflect a sense of specificity which cannot be achieved with a 24mm or 50mm lens (the lenses I used for indoor shots in the zine). Applying Latour’s logic, it is important for me as a photographer to understand the impact my seemingly simple choices may impact the viewers understanding of the message, and for my project as a whole to consider how the perspective shifts as the subjects relocate into new spaces.

Definition of Spaces and Publics

According to Jurgen Habermas, the public sphere is characterized by free, rational debate, where individuals can engage in open discussion and deliberation to reach a consensus on various issues (Habermas 1, 4, 6). Habermas saw this sphere as a vital component of publics, as it allowed for the formation of public opinion and provided a mechanism for citizens to hold governing bodies accountable. From this perspective, public protests play a crucial role in this process of holding governing bodies accountable. Protests are a form of public action that can disrupt the status quo and draw attention to issues that may be overlooked or ignored by those in power. To me, this concept carries important consequences for my photography as, in some ways/cases, it becomes the medium through which this disagreement is communicated. By understanding the role of a documentarian, it allows me to isolate what my intentions are behind a given project. In my opinion, the primary tool photographers have is their choice of framing, which inherently means we choose what to include and just as importantly what not to include. Only by recognizing this responsibility and potential for bias in my work can I achieve what I aim to in my project.

Another definition important for this discussion is Michael Warner’s description of publics as spaces of discourse that are formed by individuals coming together to discuss matters of widespread concern (Warner 1, 2, 3). Publics are shaped by the circulation of discourse, which involves the spreading and reception of messages within a given community. Publics are not homogeneous or fixed but are rather made up of diverse individuals with differing viewpoints and interests. Through the circulation of discourse, publics are able to engage in dialogues and exchange ideas in order to arrive at new understandings.

Counterpublics, on the other hand, are spaces of discourse that are formed by smaller, marginalized groups who are excluded from dominant publics (Latour 76, 77). These counterpublics are often created in response to the exclusion or marginalization of certain voices within larger publics. They allow marginalized groups to develop alternative discourses and challenge dominant narratives. Both publics and counterpublics are crucial for democratic societies, as they allow for the exchange of ideas and the formation of new understandings. However, he notes that publics are not always inclusive or democratic, and that certain groups may be excluded or marginalized within dominant publics. In response, counterpublics can provide alternative spaces for discourse and help to challenge dominant narratives and structures of power.

Again, relating these concepts back to my zine, engaging this issue through photography is essentially a method of creating a counterpublic. Is photography’s role then always to create a counter public? Personally, I would say that it is not. There are certainly projects in which creating a counterpublic is pointless or counterproductive, however this all depends on the photographer’s intention. While the intention of my zine is to accurately convey the message of the students, it is also intended to serve as a record of their effort and opinions. This conflict between oppressive forces and empowerment is key to the balance of information in each image, and one of the most significant components regarding this balance is censorship. Methodology Of Censorship

According to Simone Browne's "Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness," sousveillance refers to the act of individuals, typically those who are under surveillance, engaging in practices of surveillance themselves (Browne 12, 13, 14). It is through this perspective that I understand my role as a photographer, especially in the context of this project. While photography can certainly be used for surveillance, sousveillance is a way for marginalized individuals and communities to reclaim their agency and resist the surveillance practices that are imposed on them by those in power. To me, sousveillance is the act which I believe has the greatest positive impact. However, Browne emphasizes that sousveillance is not a perfect solution, as marginalized communities still lack access to the resources and power structures that enable effective surveillance. However, it remains a crucial tool for resistance and empowerment, allowing individuals and communities to challenge and disrupt the dominant narratives and power structures that seek to control and police them. To me this highlights the limitations of photography and reminds me that it is only a single medium through which discourse occurs. Therefore, it is my role as the photographer, in this case, to contribute to the larger counterpublic. This of course complicates the earlier discussion of roles; however, I think this conflict of mediums is critical to understand.

Marshall McLuhan argues that the medium through which a message is conveyed is just as important as the message itself, as it shapes the way we interpret and understand the message (McLuhan 23, 25, 26). In the context of photography and censorship, we can apply McLuhan's ideas to understand how the medium of photography affects the way that censorship operates. Censorship of photographs often involves the suppression of images that are deemed to be objectionable or offensive. However, the typical implementation of the medium of photography means that censorship does not just involve the suppression of specific images, but also the ways in which photographs are taken and shared (think phone vs DSLR, or print vs social media). This question of method was the greatest challenge behind the form of publication for my work, and what ultimately led me to create a zine a year after the original events occurred. I never wanted to submit my photos to a news organization, social media, or any other form of third-party distribution because of the lack of control I would then have. It was important to me for my photos to retain their authenticity while still accurately conveying the message of the protestors (and, most importantly, protecting them from the exposure inherent in posting photographs to Twitter or Instagram). To me, the ability to censor the photos was the only way to make their publication a moral decision. This, of course, raises more issues.

Tom Boellstorff discusses the "principle of false authenticity" in the digital world, which refers to the way in which digital media often presents itself as "authentic" or "real" even as it is heavily mediated and constructed (Boellstorff 41, 42, 43). This idea can be applied to how censorship in photography is viewed by the consumer, and what it implies about power dynamics in spheres of discourse. When images are censored, whether by governments or by private groups/people, the "principle of false authenticity" can come into play. Censored images may be seen as less authentic or truthful because they have been edited or removed, even though the act of censorship itself is a form of mediation and construction. This can create a power dynamic where those who have the ability to censor images are able to control what is seen as authentic or truthful, while those whose images are censored may be seen as less credible or trustworthy. This creates a situation where authenticity and truth are not objective qualities but are instead shaped by power dynamics and the ways that media is constructed and mediated.

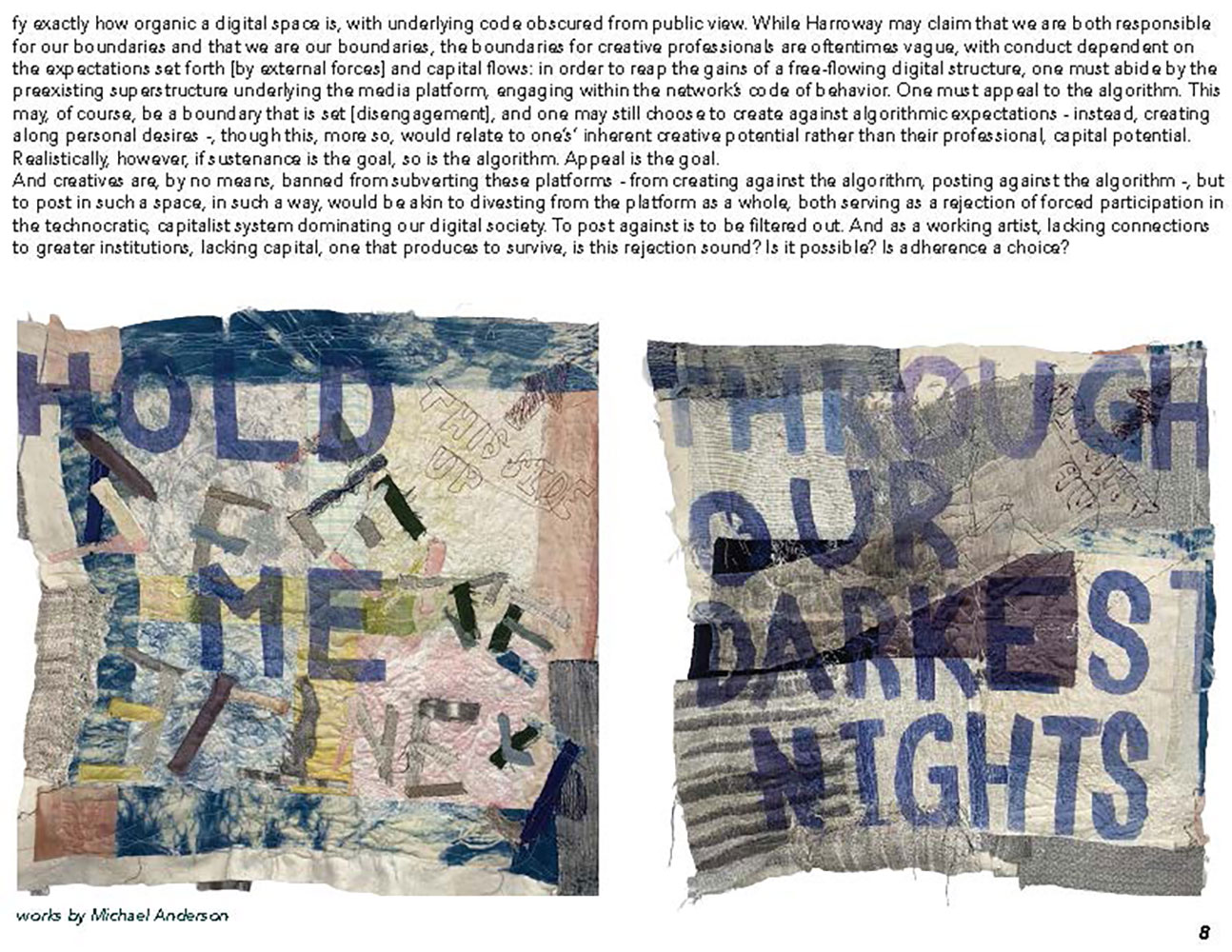

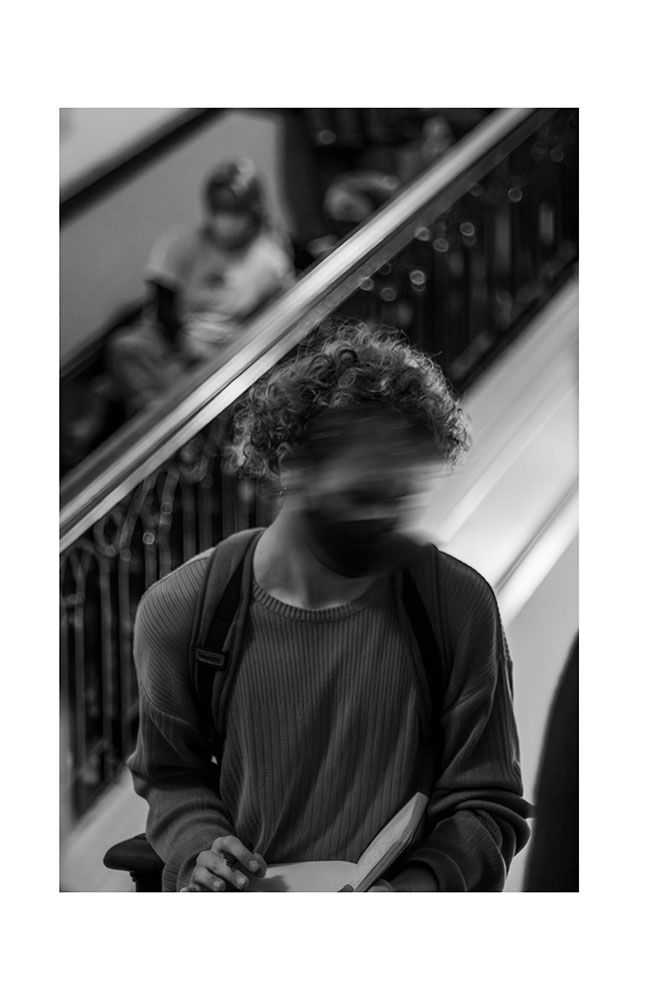

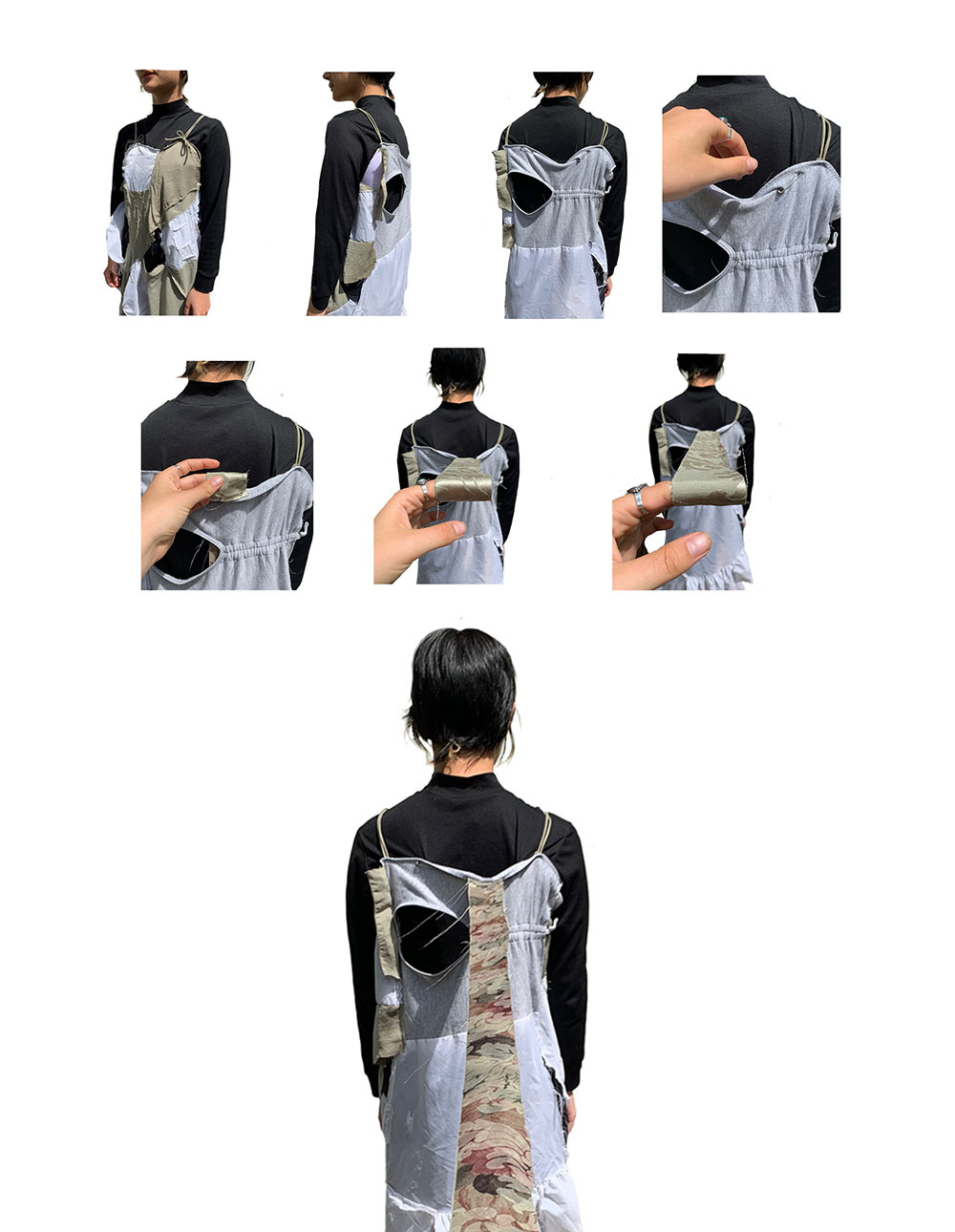

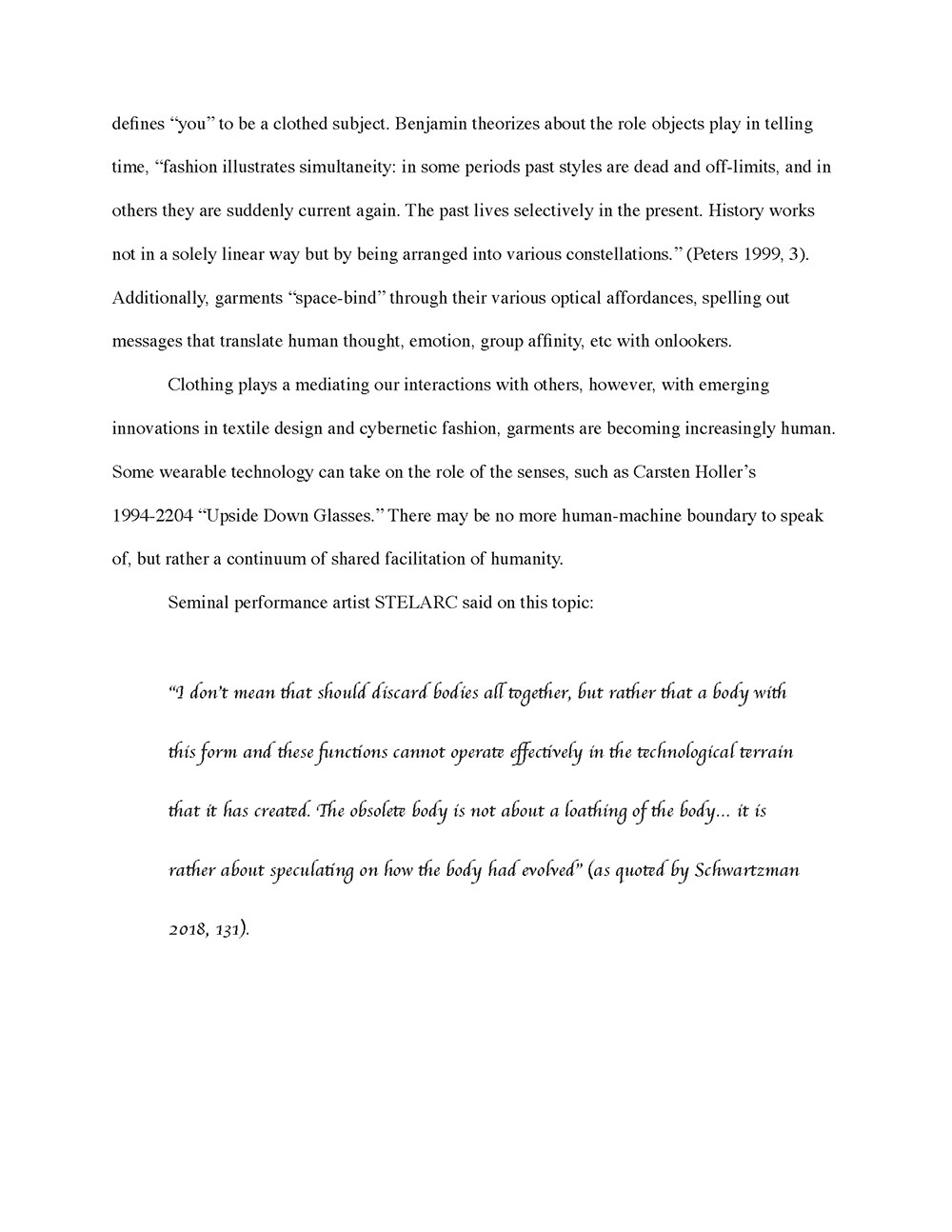

The most useful criticism I received surprised me in that it was not what or what I censored, but instead how I did so. Originally, the images were censored using a black obstruction over the entire face. However, when I showed this to my professor, they asked that I consider the implications of that method and whether or not it truly communicated what I intended to. Consider the following two examples:

The differences in these two methods may seem insignificant, however the moment I tried blurring the faces rather than marking them out the zine felt entirely different. Finally, the viewer can understand where the subject is looking. Although the face is still obscured, it still looks human. This method of censorship is less violent, retaining far more humanity in the image, in my opinion. To use the comparison made to me, it separates this case of censorship than that of the classic, brutalist corporate method of removing identity from a photo. For that reason, I feel that this method of censorship is both the most effective and sensitive method for this particular project.

Conclusion

To conclude my analysis, I have shown the ways in which my study of anthropology has informed my choices in creating this zine in respectful, intentional way. What I hope to have communicated is that the choices made by a photographer, especially in sensitive situations such as this, cannot be made lightly. Every factor related to an image a photographer makes is influenced by the publics/counterpublics it inhabits and/or creates. Specifically, the decision to censor an image, removing information, always felt like a hard thing to do right, however this project has led to me understanding the role of censorship in my work far better. In future projects, I hope to further unpack this relationship. In addition, it is important to emphasize the significance of reflecting on our own positionality and biases in relation to the communities we are studying. Regarding photography as a whole, it is crucial for photographers to continue to engage in critical reflection and dialogue with the communities they photograph to ensure that their work is respectful, ethical, and accountable in the sphere it inhabits.

Works Cited

- Benjamin, Walter. "The work of art in its age of technological reproducibility, Second Version," Selected Writings Volume 3, 1935-1938, Cambridge Harvard

- Marshall McLuhan, 2003 (1964). “The Medium is the Message," Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press Inc.

- Latour, Bruno. "A Collective of Humans and Nonhumans: Following Daedalus’ Labyrinth." Pandora's Hope: Essays on the reality of science studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Boellstorff, Tom. “Rethinking digital anthropology, Digital anthropology” Bloomsbury, 2012

- Habermas, Jurgen. "Introduction: Preliminary Demarcation of a Type of Bourgeois Public Sphere." In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 1-26, 251-256. MIT Press, 1989.

- Latour, Bruno. "A Collective of Humans and Nonhumans: Following Daedalus’ Labyrinth." In Pandora's Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies, 174-191. Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Warner. Michael. "Publics and Counterpublics." In Publics and Counterpublics. 65-124. 298-305. Zone Books, 2005.

Anna Romo – Recognizing Realities of Difference

Podcast

Essay

Anna Romo

Professor Charlene Makley

Anth. 397

9 May 2023

Recognizing Realities of Difference: To Mediate or Not?

Growing up around horses, I have been thrown, kicked, and bitten; I have struggled to understand what these animals were attempting to tell me and why they did so in a particular manner. But, at other times, I have also felt thoroughly connected – I have felt the movement of my own body mirrored in that of a nonhuman other, and I have felt completely in sync with this “other” (Argent 2012). In my podcast, Recognizing Realities of Difference: The Human-Horse Divide?, I explore the feelings of harmony and tension that exist between people and horses. Specifically, I examine the ways in which the human-horse relationship balances feelings of mediation and immediacy. While, due to its often liminal nature, mediation can be difficult to define, Dominic Boyer (2007) offers a helpful conceptual framework for thinking about just what it means to be “mediated.” For Boyer (2007, 26-7), the “medial” exists between the “poetic,” or the internal space of creativity, and the “formal,” or the external embodiment of the poetic; thus we may view mediation as the translation between the poetic (e.g., the spirit, the soul, one’s identity) and formal (e.g., the body itself, broader socioeconomic structures). Active feelings – and recognition – of mediation might develop at a moment of disjunction, where one fails, for example, to successfully communicate an idea to another person; in this instance, we become keenly aware of the role that spoken language plays in moderating our relationships with other individuals.

This paper aims to reflect and expand upon my podcast’s discussion of mediated human-horse interactions. Recognizing the assumptions and the acts of translation involved in even seemingly simple moments of communication between human and horse, I ask just what happens when these moments are mediated once more through the process of filming and publishing them online. A quick look at any animal-related photos or videos posted on social media reveals their frequent anthropomorphism; we see, as John Peters (1999) describes, this desire for immediate connection with a nonhuman other. Here, I focus specifically on people and their equine companions – rather than on any other kind of pet or animal companion – because of my own experience with these animals and because of the corporeal stakes I have found to be involved in these relationships. As I describe at the beginning of this essay, when working with such large animals a miscommunication – and a sudden feeling of being mediated – may lead to injury. Thus, I have found that feelings of successful communication, including feelings of harmony and of a lack of mediation, are a source of pride among those who care for horses. I ultimately argue that, in its attempts to feel completely immediate, the horse-human relationship paradoxically depends upon multiple layers of mediation, and it is through the disconnections between human and nonhuman – the spaces where one feels incredibly mediated, and where complete unity between the two is simply unattainable – that this relationship becomes possible in the first place.

To better understand what it means for the human-horse relationship to be mediated, regardless of its online or offline location, I want to first review my podcast and its attempt to highlight the ways in which this relationship has always been, in a sense, indirect. Scholars Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin (1998) argue that, in our ongoing desire for feelings of immediacy – truly direct experience – and immediate connection, we tend to embrace a state of hypermediacy: we want to “erase [our] media in the very act of multiplying them” (5). Inspired by their discussion of hypermediacy, or this “multiplication” of media forms that draws attention to the medium itself in an effort to create a more immediate experience, in Recognizing Realities of Difference I actively remediate the experience of riding in order to offer listeners insights into immediate sensation of riding.

As anthropologist Laura Kunreuther (2006) claims, the recording of one’s own disembodied voice tends to make “messages appear to be transparent, unmediated, and direct” (328). To make my pre-recorded voice feel ever more unmediated – to make listeners feel as though they are conversing in the same room as me – I make careful use of the word “you”: I refer to listeners as “you” to make it feel as though I am directly speaking to them (03:09, 06:59, 07:50), and in the latter, narrative portion of the podcast I refer to the horse as “you” in contrast to the “I” who speaks, thus asking listeners to assume the imaginative role of the narrator themselves (10:48, 11:20, 12:40). I also include a few “imperfect” recordings, where my voice appears slightly distorted (but not unintelligible), or where I hesitate before speaking, as a means of creating a less manufactured, more “real” listening experience that thus feels unmediated (00:54, 01:50). I further combine this sound of my voice (itself a medium) and the resulting “transparent” story I choose to tell with various audio recordings of music, hoofbeats, and birdsongs. In inundating the listener with these media in this manner, I draw listeners away from the medium of the podcast itself and into the mediated world of riding and – more generally – human-horse interactions.

With listeners able to feel as though they are directly experiencing a human-horse interaction, particularly in the story I tell during the second half of the podcast, I aim to disrupt commonly-held feelings of immediacy among those in the equestrian community. Speaking in response to John Peters’ (1999, 256) call to “[think] of communication as the occasional touch of otherness rather than” as an unmediated “conjunction of consciousness [emphasis added],” my story explores the quiet, and at times subtle, spaces in which feelings of mediation rise to the forefront of the human-horse relationship – where it becomes evident that human and horse will never truly merge into one being capable of synchronous movement, and where it is clear that certain methods of communication (e.g., the reading of body language) actively mediate this relationship. Peters (1999) claims that “driving the dream of communication with [animals] is… the desire of recognition,” for “no creature has yet stood up to say, I recognize you recognizing me” (245). My podcast pushes back against the necessity for recognition and the fantasy of complete communion between horse and human minds: in my aforementioned story, as the narrator grapples with the difficulty of developing a “true” understanding of any being outside of her own consciousness – as she grapples with this lack of immediacy, with these thoughts that mediate her understanding of the horse’s actions – there is no grand climax where human and horse suddenly, completely recognize one another.

In fact, the horse hardly appears to perceive the narrator at all. Through this lack of perception, I highlight the work that goes into creating that feeling of unmediated connection between human and horse. The horse’s aloof behavior is in sharp contrast to the ways in which I, myself, have described my relationships with these animals: for example, I have jokingly commented that a horse who did not seem to want to be brought in from pasture “wasn’t feeling me today” or “did not want to work today.” Even these off-hand comments imply a kind of shared, unmediated recognition – as though I were able to read the horse’s mind and as though the horse were able, and actively wanting, to convey her thoughts directly to me. In the absence of this anthropomorphization of horse behavior, the insurmountable disjunction – and ongoing mediation – between human and horse becomes clear. However, as Peters (1999) argues, this lack of unity – or rather, lack of “anguished communion” (31) – is not necessarily something we should strive to overcome through a fantasy of perfectly clear, immediate communication; rather, we need to embrace this otherness and recognize the joy that may be found merely in experiencing it. Hence, by the end of my story, the narrator simply sits with this otherness, content to exist outside the realm of recognition.

Recognizing that humans and horses, together, are mediated, in the remainder of this paper I aim to explore the unique realm of equine representations online – specifically on the social media platform, Instagram. Given the performative aspects of riding, and the ways in which riders continually strive to create the appearance of unmediated connection between human and horse, the questioning of immediacy – and thus authenticity – that occurs with the publication of human-horse interactions online is not new. Rather, platforms like Instagram offer an additional space both for the performance of immediate, human-horse synchrony and for the questioning of authenticity that accompanies such performed synchrony. In “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Reproducibility,” Walter Benjamin (2002 [1936]) claims that, given the sheer ease with which one can edit, cut, rearrange, and reproduce video, when captured on film the actor is completely alienated from his aura, or “his [unique] presence in the here and now,” and is thus made inauthentic (112). Therefore, according to Benjamin, we might argue that the human-horse relationship loses its authenticity when it is filmed, posted, and reproduced on social media. We see suspicions of the extent to which social media posts authentically represent interactions between people and their equine companions – hinting at an assumption that it is impossible for these interactions to be truly as unmediated and completely cohesive as they appear – in the desire to publish “fails,” or videos wherein horse and human fail to cooperate. For example, under Zoe Luna’s (2022) Instagram video of her young horses bucking while being ridden, one comment thanks Luna for “posting something real,” as “baby horses are far from perfect most rides” (Dittmar 2022). Publication of these moments of miscommunication – where it is clear that human-horse interactions are mediated and imprecise – are meant restore the authenticity of this relationship; capturing and posting moments of disharmony hint at “unedited” video that has not been reproduced and stripped of its aura or uniqueness.

Yet, in my experience, this questioning of authenticity has not developed solely with the rising popularity of social media and mobile recording devices. The ironic dependence upon the periodic visibility of moments of mediation between horse and rider, moments which serve to ameliorate any perceived loss of authenticity, persists in the offline world, in the absence of the camera, as well. When I ride, I am acutely aware of my appearance and my horse’s appearance; I strive to appear fluid and relaxed, but not so relaxed that it seems as though I am not asking my horse to position himself in a certain way: I need to make just enough of this mediated relationship visible as to convince onlookers that I am, in fact, asking my horse to behave in a particular manner. Paradoxically, in making the mediation involved in my riding more apparent, the experience of seeing my ride becomes more “raw” and unmediated; it becomes clear that my riding is “real” riding.

Given Tom Boellstorff’s (2013, 50) claim that the “gap between online and offline is culturally constitutive, not a suspect intellectual artefact to be blurred or erased,” I would argue, in turn, that online representations of horses enact a particular fantasy of immediate connection that spans both online and offline spaces and that depends upon the context provided by each. The online Instagram page becomes “an additional space for personal expression” (Miller 2011, 169, as cited in Boellstorff 2013, 50); it becomes a space to explore both the boundaries of one’s own understanding of the human-horse relationship and one’s fantasies about this relationship.

Thus, while the quest for immediacy – produced at least partially through evident feelings of mediation – persists in both the online and offline space, the ways in which people achieve this immediacy varies depending on their online or offline location. For, in contrast to the offline world, where disruptions between human and horse are commonplace, and where the creation of immediacy involves the very appearance of these disruptions themselves, online we can demand the recognition – the immediate connection – that Peters (1999) claims we so desire from these animals; this creation of immediacy both depends upon the fact that it does not entirely exist in the offline world and upon the ease with which equestrians online may appear as though they have unmediated access to the very “soul” of the horse itself (245). An Instagram post of my own, made in the summer of 2017, illustrates this point nicely: the caption of the post reads, sarcastically, “Try a little harder!” and the photo depicts myself on the back of a horse jumping in good form. In asking this horse to “try harder,” I suggest a kind of dialogic relationship between human and nonhuman; I suggest that the horse hears what I am asking for and is capable of responding in kind. Here, like other equestrians on Instagram, I recognize the gap between human and horse consciousness in my very attempts to eliminate it – my question is an effort to bridge the disconnect. Because of its impossibility offline, online representations of horse-human relationships effectively create a space where horse and human minds merge in unmediated fantasy.

Nevertheless, it is the disconnect between human and nonhuman that makes it possible for humans and horses to establish a relationship in the first place. This relationship – whether online or offline – relies on the dual feelings of mediation and immediacy that come from the insurmountable gap between self and other. And though equestrians may engage with the sheer “otherness” of nonhuman animals on a daily basis, Peters (1999) leaves us with the question of just how a conscious effort to “sit with” this otherness – rather than persistently attempting to create feelings of unmediated connection – might change our very understanding of these engagements.

Works Cited

Argent, Gala. 2012. “Toward a Privileging of the Nonverbal: Communication, Corporeal Synchrony, and Transcendence in Humans and Horses.” In Experiencing Animal Minds: An Anthology of Animal-Human Encounters, edited by Julie A. Smith and Robert W. Mitchell, 111-128. New York: Columbia University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2002 (1936). "The work of art in its age of technological reproducibility, Second Version.” In Selected Writings Volume 3, 1935-1938. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bolter, J. David and Richard Grusin. 1998. “Introduction.” In Remediation: Understanding New Media, 1-15. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Boyer, Dominic. 2007. Understanding Media: A Popular Philosophy. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Dittmar, Amelia (@amelia.dittmar). "Thank you for posting something real." Instagram, July 2022. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CgA2F8xp4Rn/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=

Kunreuther, Laura. 2006. "Technologies of the Voice: FM Radio, Telephone, and the Nepali Diaspora in Kathmandu." Cultural Anthropology 21(3): 323−353.

Luna, Zoe (@zlequestrian). "I thought everyone would get a kick out of some of the young horse shenanigans going on the last couple of weeks!" Instagram, July 14, 2022. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CgA2F8xp4Rn/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=

Peters, John Durham. 1999. “Machines, Animals, Aliens: Horizons of Incommunicability.” In Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication, 227-261. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peters, John Durham. 1999. “Introduction: The Problem of Communication.” In Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication, 1-31. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Romo, Anna (@a.nnie_cr). “Geeze Capone try a little harder.” Instagram, December 27, 2017. Accessed May 2, 2023. Archived post.

Tom Boellstorff. 2013. “Rethinking Digital Anthropology.” In Digital Anthropology, edited by Heather A. Horst and Daniel Miller, 39-60. London: Berg.

Works Cited in the Podcast:

Recognizing Realities of Difference: The Human-Horse Divide?

Scholarly Works Cited

Bolter, J. David and Richard Grusin. 1998. “Introduction” in Remediation: Understanding New Media, 1-15. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gershon, Ilana. 2010. “Breaking Up Is Hard To Do: Media Switching and Media Ideologies.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 20, 389-405.

Peters, John Durham. 1999. “Ch. 6 Machines, Animals, Aliens: Horizons of Incommunicability” in Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Audio Works Cited

Bruno.auzet. “Soft rain drops.wav.” Freesound. December 12, 2022. Wave audio recording, 03:12. https://freesound.org/s/664162/.

Buzzatsea. “Nature beautiful bird calls.” Freesound. March 10, 2021. M4a audio recording, 00:32. https://freesound.org/s/562864/.

Director89. “Rain-Atmo.WAV.” Freesound. March 3, 2015. Wave audio recording, 00:29. https://freesound.org/s/265627/.

Dosi x Wishes and Dreams. “Lost Souls.” Lofi Records. January 31, 2023. YouTube video, 02:47. https://youtu.be/UVmyQsHHpI0.

Dr. Macak. “Forest wind and birds.” Freesound. November 16, 2020. Wave audio recording, 03:16. https://freesound.org/s/544889/.

Kyles. “Foliage leaves rustle brush movement.flac.” Freesound. June 9, 2022. Flac audio recording, 00:47. https://freesound.org/s/637547/.

Lenni Loops x stream_error. “The Earth From Above.” Lofi Records. February 6, 2023. YouTube video, 02:06. https://youtu.be/e6IG6tJp1kE.

Living Room, Otaam & Phlocalyst. “A Friendly Hello.” Lofi Records. February 23, 2023. YouTube video, 02:11. https://youtu.be/8_LHmBLWPYg.

Maiso Linua. “Semai.” Lofi Records. March 9, 2023. YouTube video, 02:48. https://youtu.be/cYd6AsDxKzc.

Motion_S. “Grass Footsteps.” Freesound. March 5, 2014. Wave audio recording, 00:20. https://freesound.org/s/221756/.

Soundslikewillem. “Snorting horse.wav.” Freesound. February 17, 2018. Wave audio recording, 00:07. https://freesound.org/s/418427/.

Maya Ronen – The Zine Diaries

Zine

Essay

Maya Ronen

Charlene Makley

ANTH 397

5/11/2023

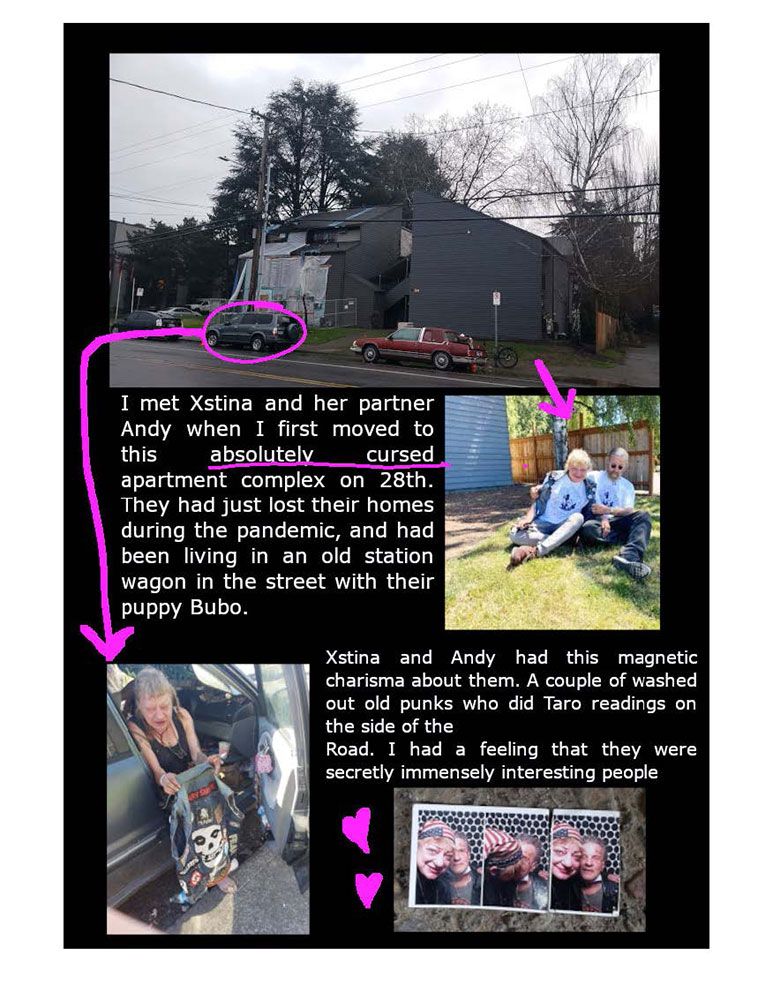

The Zine Diaries: an explanation

When I was writing “The Zine Diaries”, I wanted to tell a story about my encounter with a particular medium, that medium being Zines. I wanted to talk about the story of a person that I am close with and the people that she was close with in turn. Above all, I wanted this to be the sort of project that is accessible to everyone. As such, some of the finer points and academic sources were not included in this project; their home is here, in this explanation.

Here, I want to take a moment to talk about media (in this particular case, Zines) and their tendency to amass certain kinds of publics. As Michael Warner notes in Publics and CounterPublics, any form of media that has an addressee of some kind creates its own public. As such, the media creates what Warner refers to as a “relation among strangers” (74). The public is something that draws the attention of strangers to a common locus of information to be shared and circulated (87-89). Thus, anything addressed to a general audience in the form of readily sublimated media can be conceived of as creating a general “public”. The Counter Public, in contrast, is much like a public in that it draws together an assumed audience of strangers, but unlike the Public, the Counter Public circulates information that is often directly against the public. People become marked and recognizable by their participation in this sort of discourse because it is the sort of conversation they participate in (120).

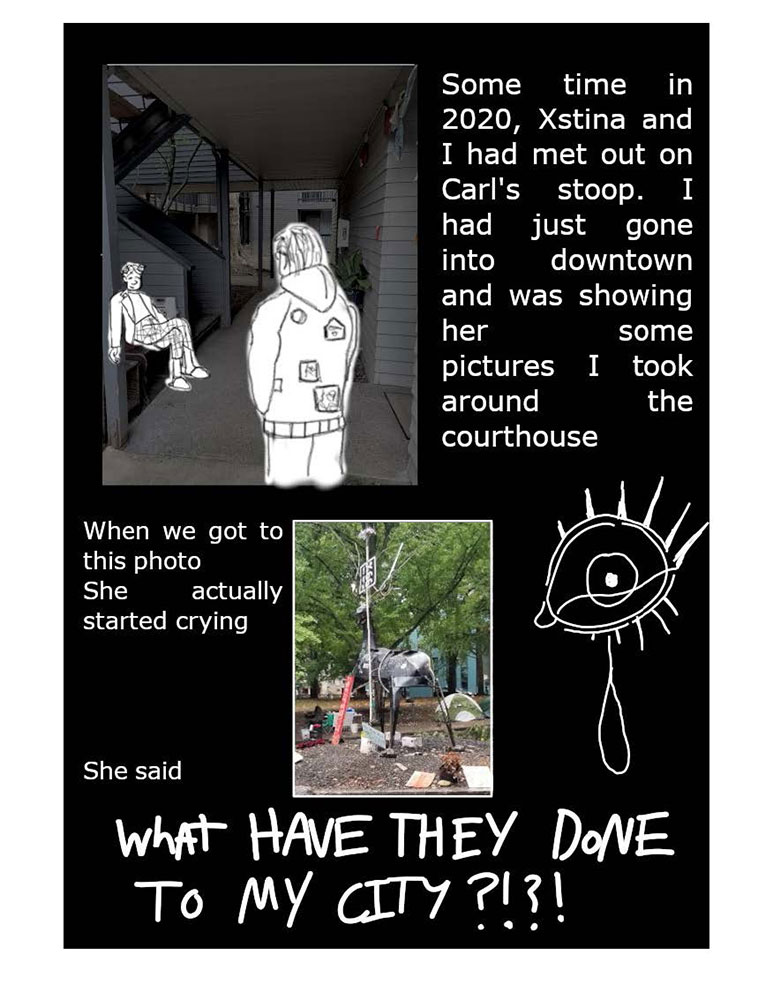

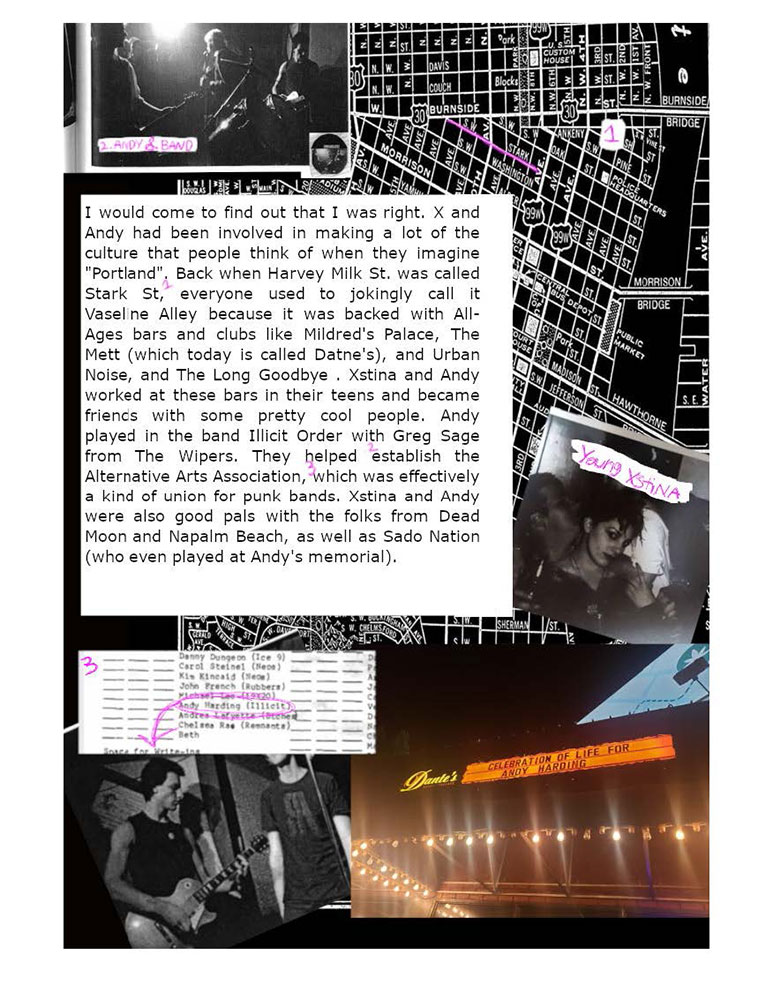

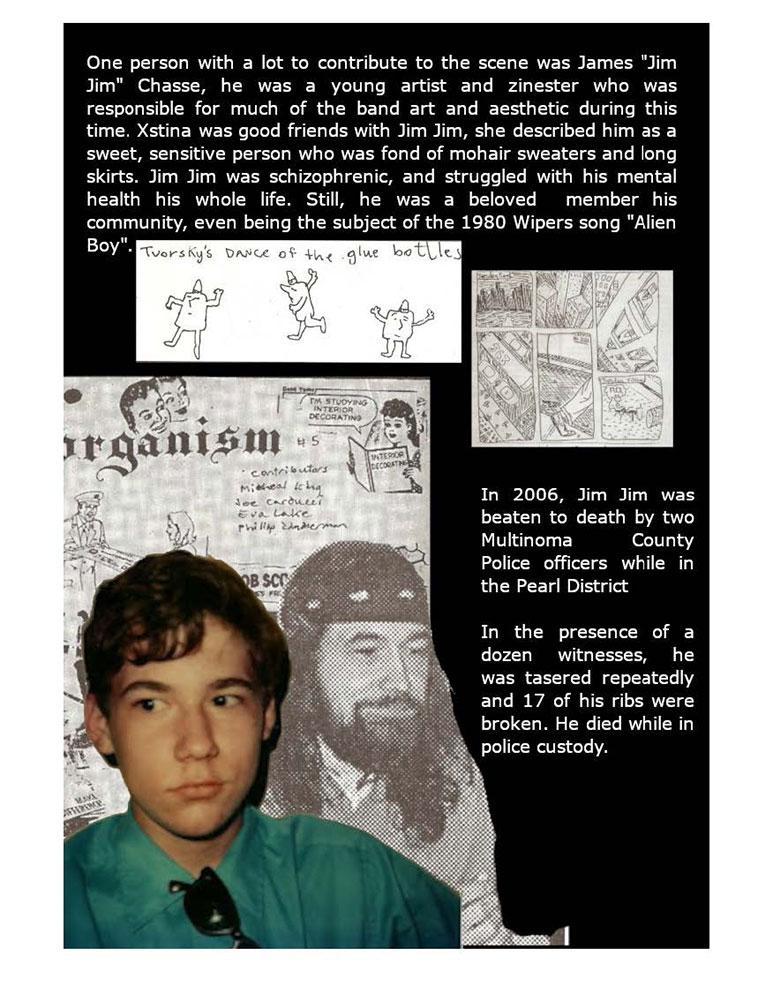

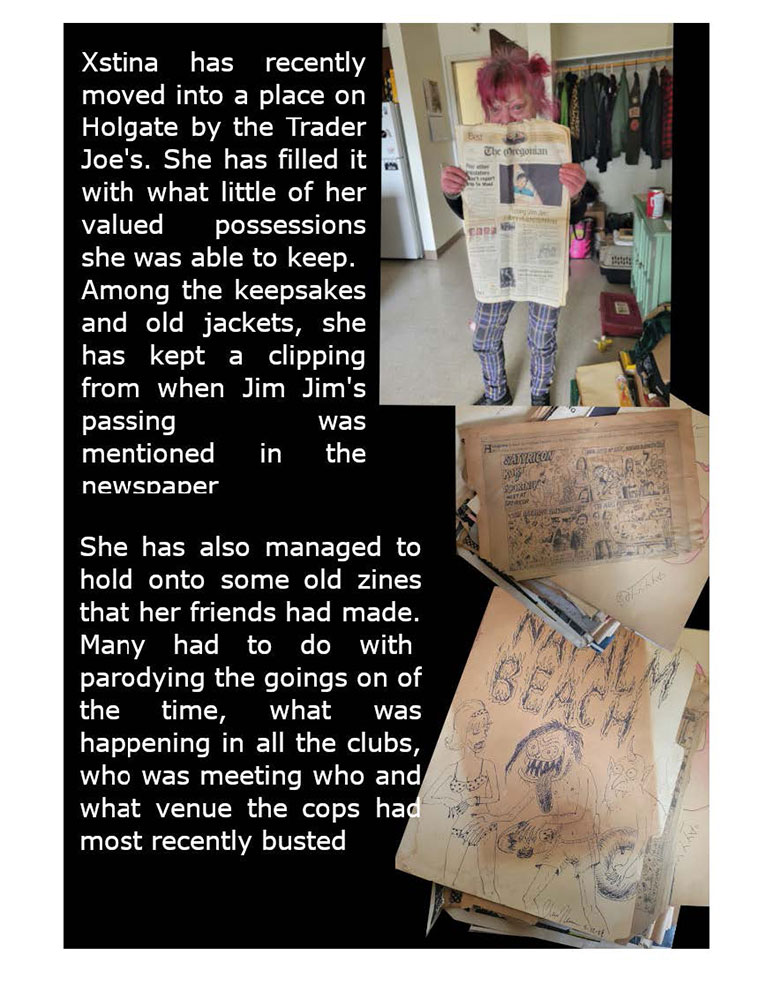

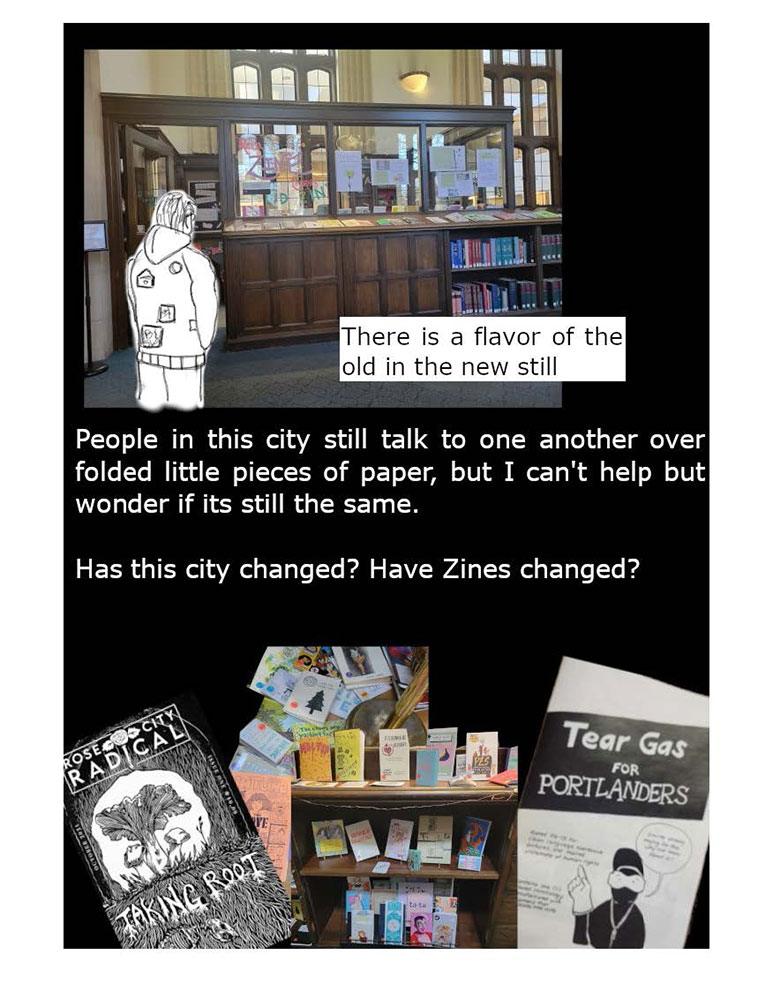

Zines were historically built for creating this kind of public. These were small, readily distributable works that were effectively underground publications of comics and essays that often didn’t have a place in the mainstream media, as they often incorporated stringent criticisms of the establishment or themes (like Queerness) that were considered too risky for a mainstream audience. This is especially evident in the zines of Jim Jim Chasse which often were explicitly anarchist in their imagery. It is telling that many of today’s zines have maintained the same antiauthoritarian stances, with one zine I noted at the library being called “Tear gas for Portlanders” being a “for dummies” style guide on how to safely encounter teargas in the event of police countermeasures at a demonstration.

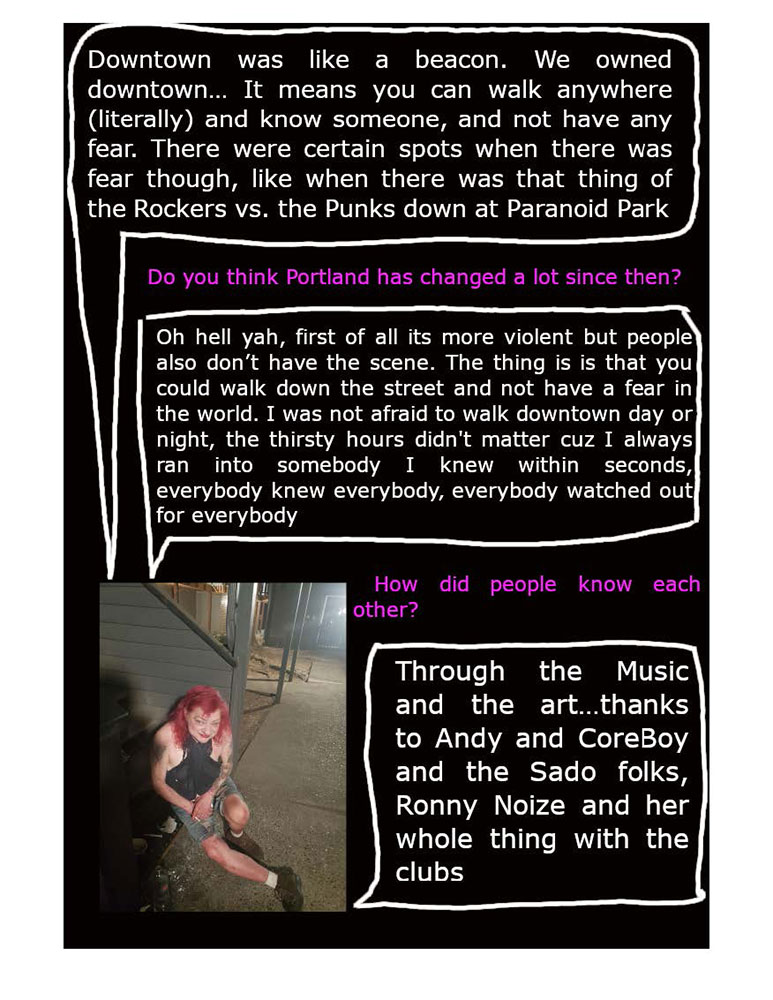

There is also something worth noting here about the kind of “Stranger Sociability” of counter publics which Warner rather briefly touches on: since the participation in a counter-public marks one as being “othered” it robs the participant of a sense of anonymity, and thus, of their very status as “strangers”. Participants in counterpublics are in practice not so much complete strangers as they are comrades. In the case of the early Punk scene, this is made evident through the ability to recognise someone as a Punk in downtown as per Xstina’s description. Even without the appropriate regalia to distinguish one as a Punk, they are still recognisable through their participation in certain publics, through their attendance in certain clubs and bars. Within Xstina’s example, even if she did not know the person personally, they were likely someone she saw as the Mett, or Urban Noise, or Clockwork Joe’s, or any of the other establishments around Portland that catered to her particular public. The overwhelming presence of such people within the city and their visible public nature contributed to the sense that Xstina and her friends ``owned” Downtown.

Still, this is a Zine in part about the changing landscape of Portland, how this kind of “stranger sociability” is slowly but surely becoming a thing of the past. The landscape of the city is currently such that patronage to certain bars and clubs does not constitute membership to a public. Perhaps it is due to the affordances of technology that allow people to connect with their intended “public” on their own terms, but in my experience, it has become increasingly more difficult to seek out connections through in person conversations. Here, one can’t help but consider Seaver’s analysis of the anthropology of algorithms. “ Algorithms, we can say, are culture—another name for a collection of human choices and practices” (Seaver 2017). What the algorithm on your phone accomplishes is really a streamlined version of connecting you to the appropriate publics and people within. You don’t need to go to Dante’s anymore to meet fellow punks, you just need to follow the appropriate content creators.

The algorithmic medium might be part of the reason why, in spite of the changing landscape of Portland, Zines have remained remarkably popular. While Zines got their start in a paper medium, they lend themselves very well to being shared across social media. Since zines often have a subversive or political element to them, their distribution across social media can be constitutive of what might be called “digital activism”, to borrow a term from Bonilla. The distribution of Zines on social media (particularly those pertaining to Portland) allow people to foster a collective consciousness of what is happening in their city and the ways in which they can get involved in collective action.

In reflecting on the persistence of this culture, I conclude my Zine by noting how even though the atmosphere of Portland has changed, that Punk Rock rebelliousness has stuck around. This is evident enough through the distribution of Zines. As Marshal McLuhan famously stated, “The medium is the message”. Put differently, the message of a given medium is integrally tied to the affordances of that particular medium. A medium that is independently produced and easily circulated lends itself to a message that is underground, community oriented, and against the “status quo”. In other words, the very presence and persistence of Zines, especially those with anti-authoritarian leanings, is evidence that there is at least part of Portland that maintains its Punk sensibilities.

“A Brief History of Zines.” 2016. Mental Floss. November 19, 2016. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/88911/brief-history-zines.

Alien Boy (2013). n.d. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://tubitv.com/movies/508207/alien-boy.

Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. “#Ferguson: Digital Protest, Hashtag Ethnography, and the Racial Politics of Social Media in the United States.” American Ethnologist 42 (1): 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12112.

Harvester. 2012. “Remote Outposts: ALIEN BOY - ‘A Zine About the Life of James Chasse’ - By Erin Yanke and Icky A. - 2006.” Remote Outposts (blog). September 10, 2012. https://remoteoutposts.blogspot.com/2012/09/alien-boy-zine-about-life-of-james.html.

McLuhan, Marshall, and W. Terrence Gordon. 2013. Understanding Media : The Extensions of Man. Berkeley, California: Gingko Press.

“Portland-Based ‘Puncture’ Magazine Upped the Game for Punk Rock Zines. A New Anthology Shows How.” 2020. Willamette Week. September 23, 2020. https://www.wweek.com/arts/books/2020/09/23/portland-based-puncture-magazine-upped-the-game-for-punk-rock-zines-a-new-anthology-shows-how/.

“The 10 Greatest Punk Zines of the Eighties | by Michael Hardy | Vesto Review | Medium.” n.d. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://medium.com/vesto-review/the-10-greatest-punk-zines-of-the-eighties-1f9085614caa.

Warner, Michael. 2002. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.

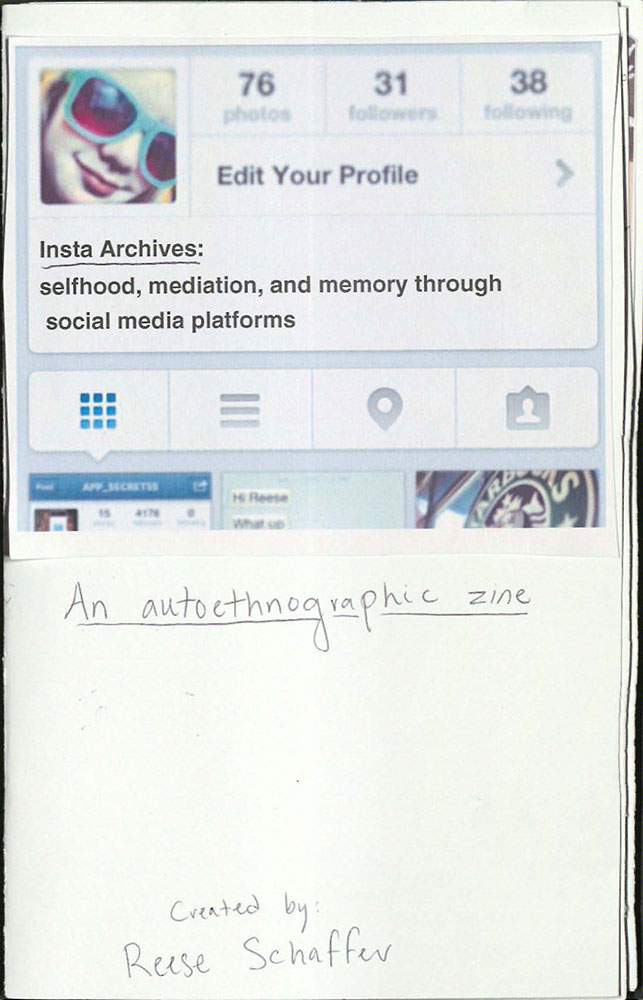

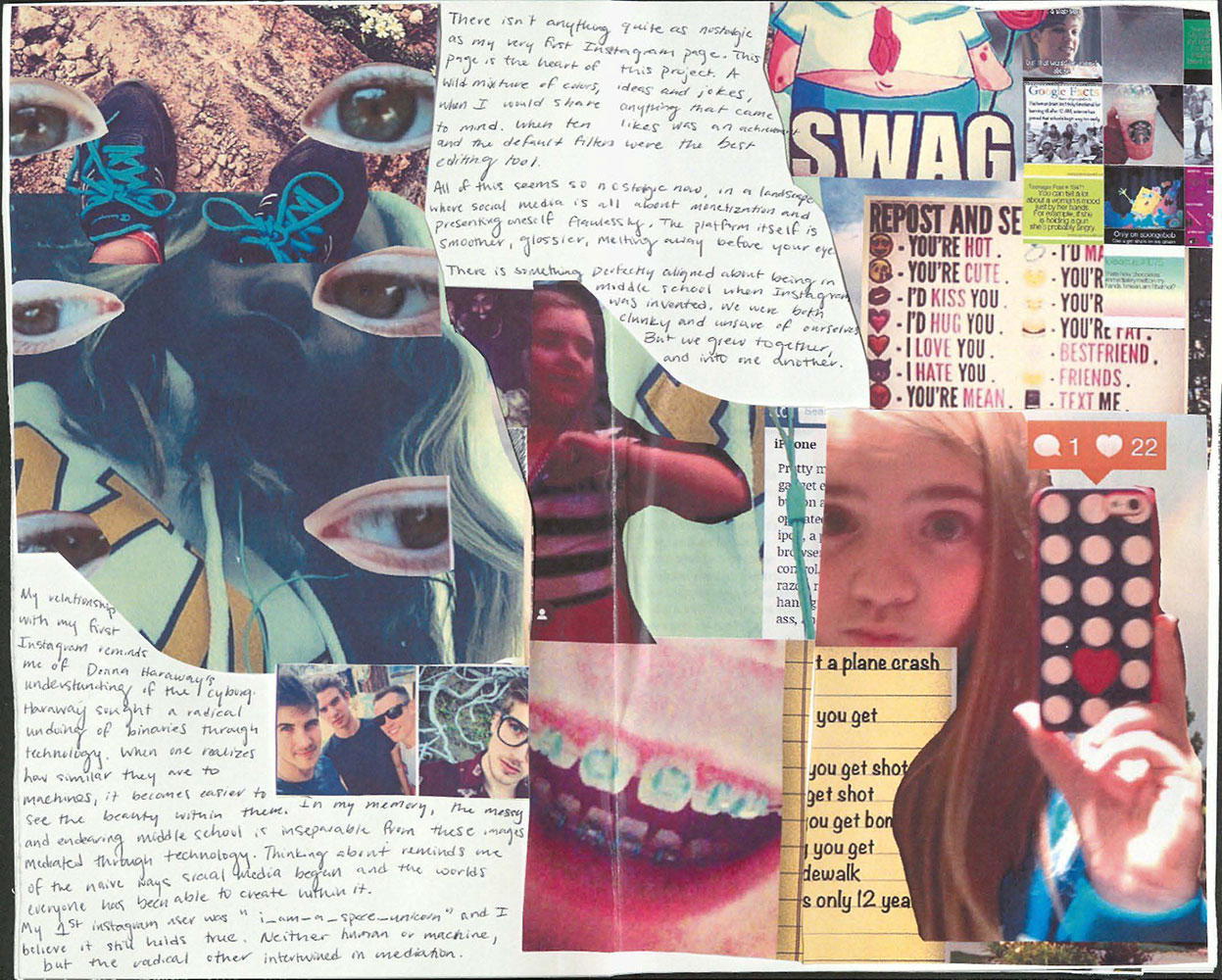

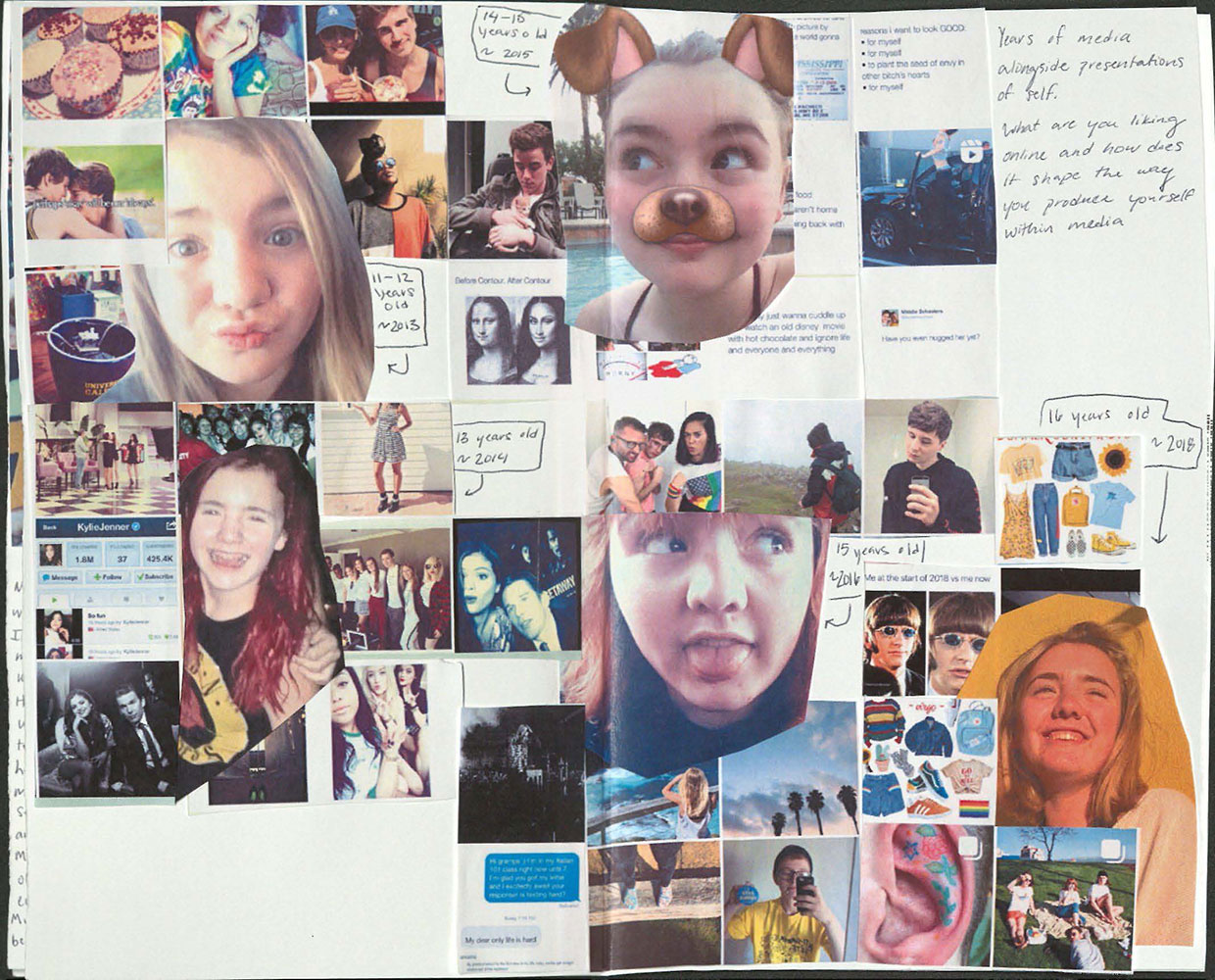

Reese Schaffer – Insta Archives

Zine

Essay

Reese Schaffer

Charlene Makley

Media, Persons, Publics

9 May 2023

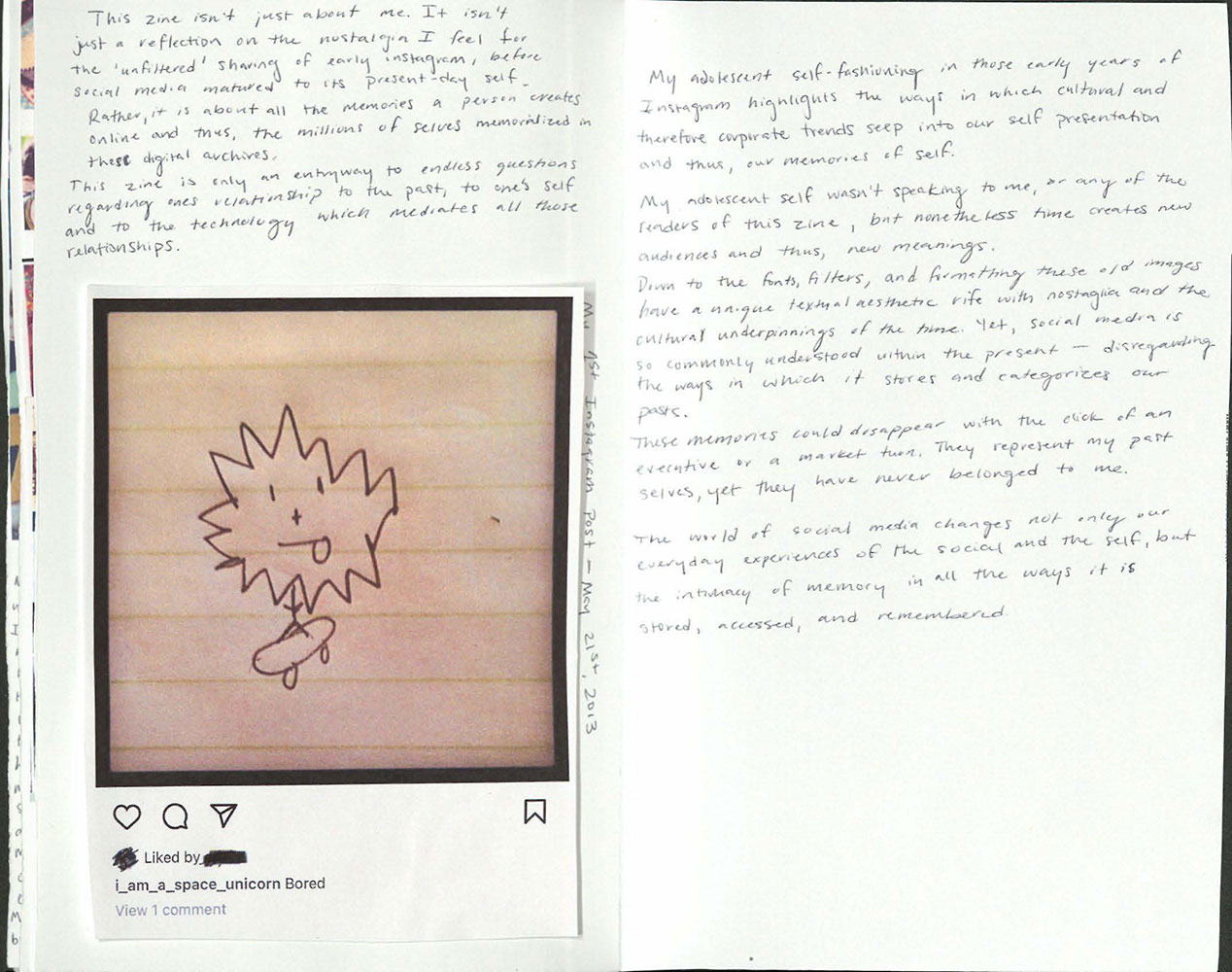

Insta Archives: Theoretical Extensions of Mediation and Memory

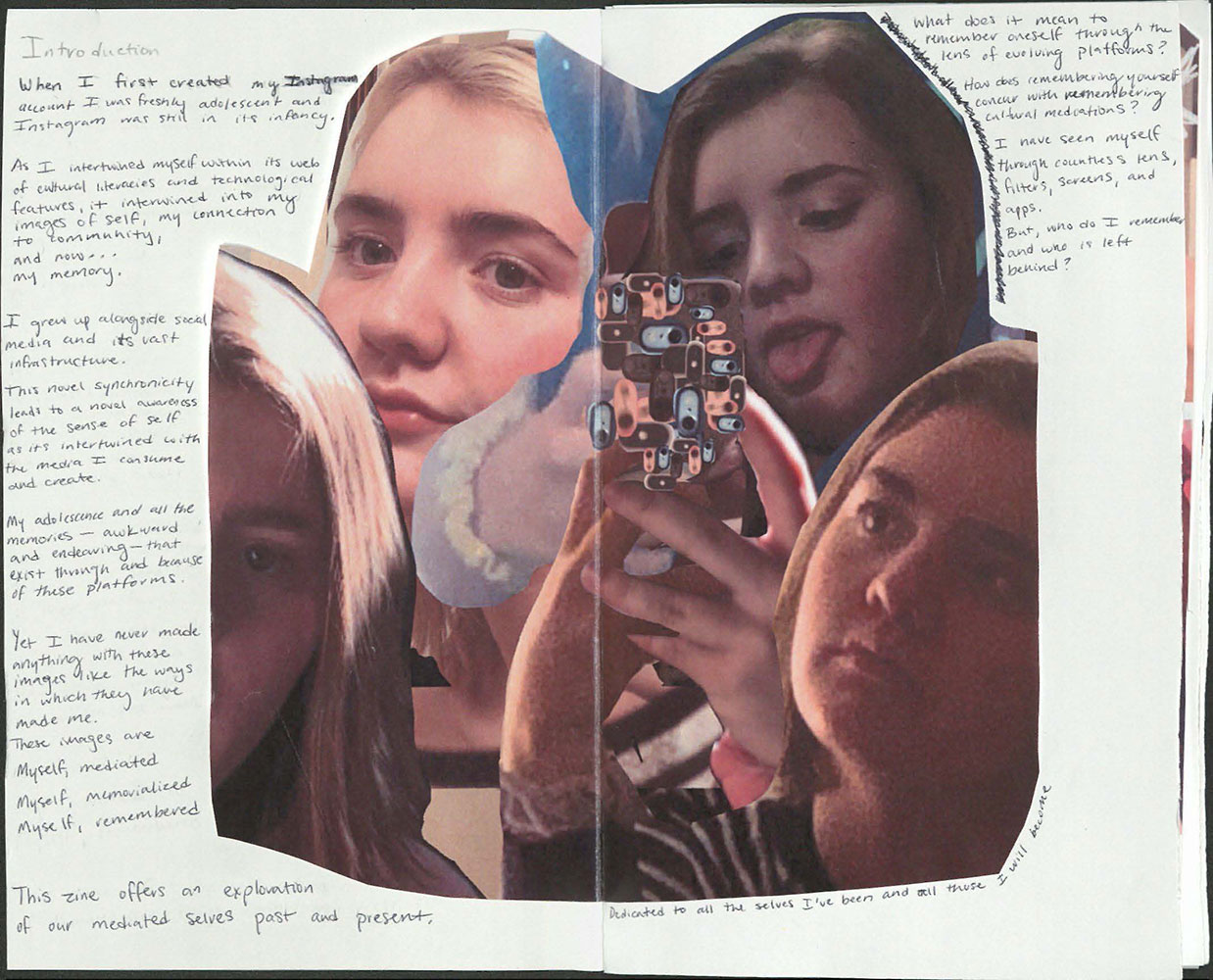

This project was a long time in conception and only recently actualized within the context of anthropological theory and practice. The internet and my own personal relationship to it is something that I have been thinking very deeply about for a very long time. Thus, this project, the zine, and the theories in which I draw from are by no means putting an end to my questions surrounding these relationships. Rather in a moment where something is so large and personal that you really don’t know where to start, I chose to start with myself. I chose to look inward and focus on the most personal and intimate aspects of my life online so far, and that is the memories of my adolescence encapsulated in my old social media accounts. Specifically, this project focuses on my very first Instagram account. Looking back, I feel the same nostalgia flipping through old diaries as I do opening up that old Instagram page. My first Instagram account was a public diary. Through a mismatching of images of my friends, low resolution memes, and text posts that I had created, that grid of images represents a moment in my life as well as a moment in technological time. It was a wonderful synchronicity in which I was young and so was the technology in which I fashioned myself through. But now the foresight to what those social media platforms would become and the wild array of problems to which our addictive relationships with social media have led, I seek to look back on these seemingly more simplistic times. This project attempts to reflect on what these moments of adolescence and my memory of them mean in the greater web of technology and personhood. How does the simplicity of a childhood Instagram account reflect the complex relationships of selfhood, memory, and technology? In what ways does growing up with social media reveal the ways we both shape and are shaped by the media of which we consume?

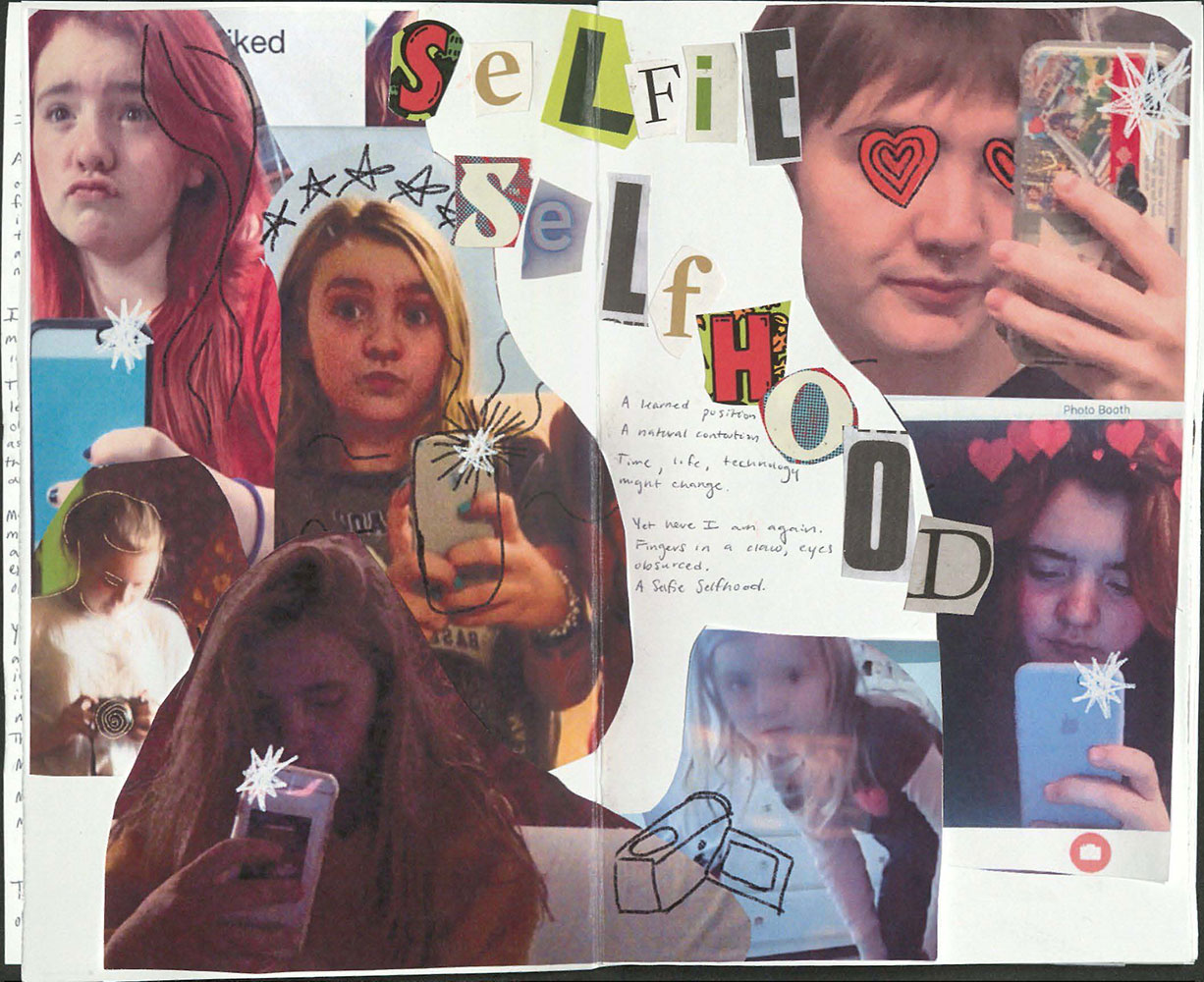

I chose to do this project through an autoethnographic zine largely because I was really curious about what I could create out of this very static grid-form collection of images from my adolescence. The zine and collage format really lends itself to exploding the static layout in which Instagram affords, allowing one to think about the ways in which reality and media become mashed together. I want to allow a lot of the zine to stand for itself, in that it is both deeply personal– in revealing the embarrassing images of myself from a universally awkward period of one's life (the “tweens”)– and in that it is a collection that seeks to capture the experience of growing up online through the products created within in. This written piece seeks, rather, to connect the background of theory on media and personhood to deepen this exploration and ground it in larger questions outside of that of a singular Instagram account or my own personal experience. There is quite the breath of theoretical underpinning that could be coupled with this notion of mediation, memory, and selfhood online and therefore I will briefly introduce a variety of inquiries. I will attempt to cover three main lines of inquiry into theory– theories regarding selfhood within technology, theories of the media itself and its representation, and theories of infrastructure and publics. These all represent separate directions in which one could approach this topic, of which I attempt to introduce in this zine.

To begin, I position theories regarding the creation of selfhood online alongside cyborgian theory per Donna Haraway. These understandings both center around the intertwined relationship between oneself and the media one produces and consumes. Haraway’s perspective takes a radical liberatory approach in claiming that the erasure of dualisms such as self/other, mind/body, and reality/appearance, society will realize the insecurity within a singular self and rather come together as a collective society against oppressive forces (Haraway 1991, 177). This approach might overestimate the ability to overcome the oppressive systems through technological advancement but does introduce the potential of blurred boundaries and intertwined subjecthood between human and machine. This plays into the relationship one coming of age fosters with the media they produce, because memory-making through mediated forms causes the mechanical affordances of the media itself to become inseparable from your own past image. The notion of the ‘microtrend’ is helpful in categorizing the fast pace in which people adapt their own personhood to the larger cultural (and inherently consumer) trends (Agha 2011). This extends the notions of the cyborg incorporating the ways in which social media selfhood commodifies the user. Alongside this, memories embedded in these platforms become embedded not just in the fast paced social trends, but in the desires of the companies and organizations that control the data. Yet, as they become memory those capitalistic desires become a part of the media and sense of self one leaves behind. Within these notions, my nostalgic relationship to my past self through these media, also becomes a nostalgic relationship to the media platforms and technologies of the time. Which in turn, allows the corporations which own the mediated memories themselves to have control over nostalgic remembering in new ways. Memories and the selfhoods created through media thus are enmeshed in technology in their creation and in our own future revisiting.

Alongside personhood, the media itself becomes intertwined between these cultural, economic, and personal relationships in its representation. This draws on Walter Benjamin’s notion of the technological aura, which he posits decays with increased technological advancements (Benjamin 1936). Yet, with this exploration I find that the aura is a useful basis for understanding the aesthetic imagery of hyper mediation. The ways in which memes, formats, and filters create an image of a certain time period adds an ‘aura’ to images– even those which don’t include any of these formats. I explore this in the collage spread in which I layout images of myself alongside my likes at the time– showing the ways in which the aesthetic culture of media one consumes shapes with how one produces their own image (especially through formidable ages). This coincides with notions of affordances– what the technology enables a user to do with it. Thus, the fonts, formats, and picture sharing features of Instagram affords the user the ability to create this kind of personal diary entry relationship, but also mediates how that relationship is created and thus, how it is remembered. Drawing back to the ideas of personhood, the self in this context cannot be separated from the aura and affordances of the technology and thus, must be remembered within them. The act of remembering within hypermediated forms complicates notions of immediacy in both one’s sense of selfhood and the act of remembering.

Finally, I want to position the networks in which media creation in social media is intertwined. Namely, the publics which are created and the infrastructures that upholds media. In conversations with notions of memory, these structures complicate the meaning of digital media as it lasts through time online. In terms of publics, which refer to the collection of people who are conjoined through their involvement and interaction with a discourse (Warner 2002). Thus, even in such a small scope, the group of people that viewed and interacted with my Instagram in 2013 (other adolescents) are a public, but so is the group of people interacting with the same media again through this zine. Therefore, the public involved in this media changes, and so does the meaning the media conveys. I think this is evident in cultural events where old posts are brought to light and suddenly viewed in a new way within the context of the present. The consumption of media online creates a feeling of immediacy, even when knowingly consuming old posts and conversations, thus interaction with old media on the internet creates renewed and current meanings outside of their original context. On the other hand, infrastructure is all about the material scaffolding which is necessary in order for this media to persist throughout time. Memory-making within this scope is always reliant on a system of technology, workers, and logistics to maintain the media over time (Larkin 2008). Over the course of gathering images for this project, I was reminded of the shutdown of Vine which was a pivotal media making application during this time period that shut down as a company and no longer exists. Therefore, when thinking about self-making within these contexts it is necessary to acknowledge the infrastructure which although is seemingly invisible, now has a large share of the control over the memories one has (and doesn’t), and thus what can be remembered and how.

This additional written portion in accompaniment of the zine is a very brief exploration of the very complex issue of technology, media, and remembering. There is so much more to be said, to be questioned, and to be discovered regarding our use of technology and the memories which have become embedded within it. Theories of memory, archive, and self have largely been separate from digital media theories, so I seek here to bridge that gap and point out all the ways in which mediated memories pose specific and novel lines of questioning. Yet, this project is only the beginning, for these questions aren’t close to being answered both theoretically and in terms of my own personal self-reflection alongside these theories.

Works Cited

Agha, Asif. 2011. “Large and Small Scale Forms of Personhood.” Language & Communication 31 (3): 171–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2011.02.006.

Benjamin, Walter. 2002. “The Work of Art in Its Age of Technological Reproducibility, Second Version,.” In Selected Writings Volume 3, 1935-1938. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Haraway, Donna. 1991. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Roudedge.

Larkin, Brian. 2008. “Introduction.” In Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Warner, Michael. 2002. Publics and Counterpublics. Zone Books.

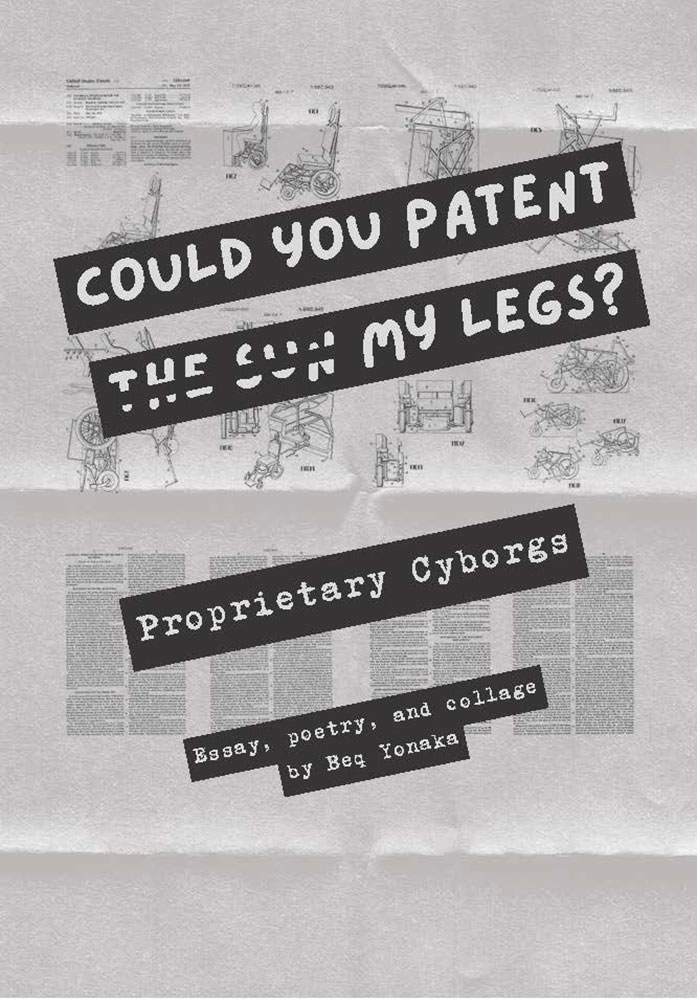

Beq Yonaka - Proprietary Cyborgs

Zine

2020

Quinn Chen – Media Studies: Textiles

Zine

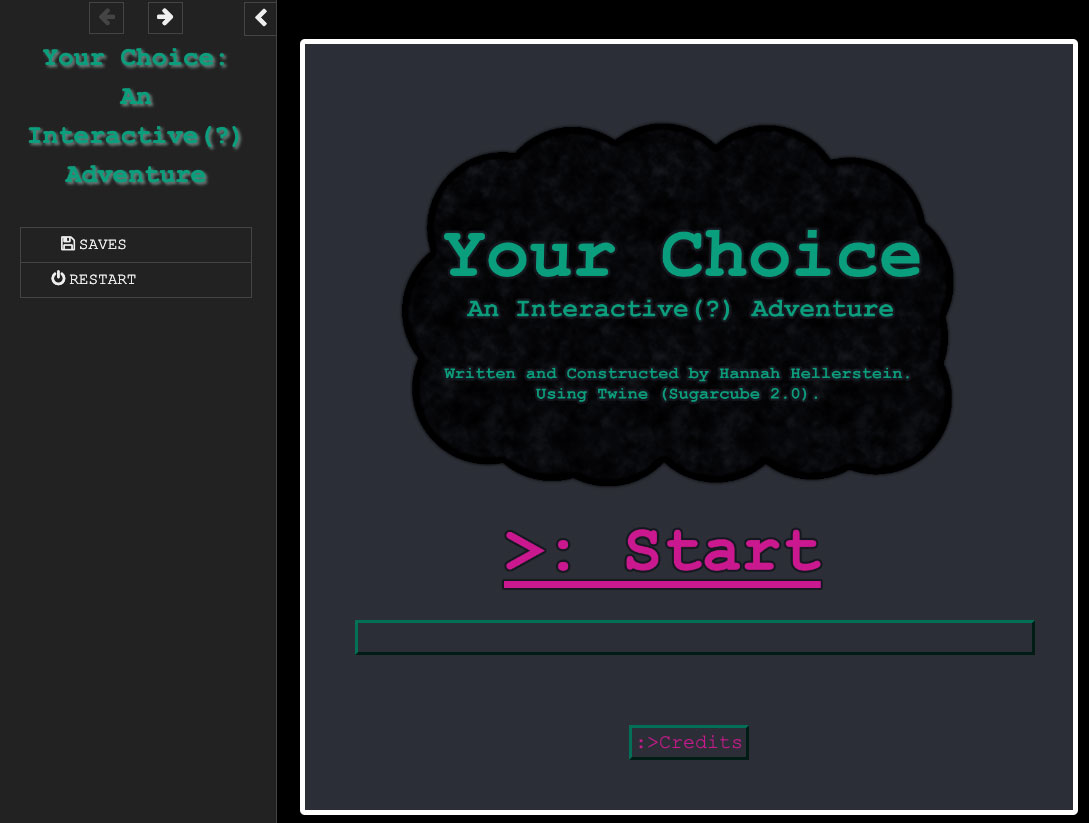

Hannah Hellerstein - Your Choice: An Interactive (?) Adventure

Essay

Hannah Hellerstein

5/10/2020

Media Persons Publics Final Project Discussion