Study Guide Household

Table of Contents

Material Possessions

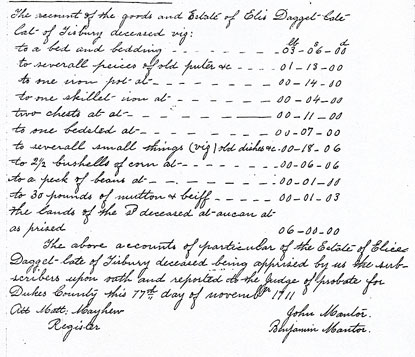

Wills and estate inventories such as that of Elis Daggett (below) are an important resource for assessing the material possessions of households on the Vineyard. Wills not only reveal what objects Wampanoags and whites owned, but also which ones they felt were valuable enough to pass on to others. Gift exchange, including goods bequeathed at death, are an important way of solidifying and creating bonds among kin and community members. In Puritan society, gifts –like hospitality more generally--were a way of paying allegiance to higher authorities. In Algonquian communities, gifts given by social superiors were also a way of creating obligations upon lower status members of the community. These obligations  could persist after death, either by re-cementing the relationships of the family to community members (for example to one’s minister) or by ensuring proper respect for one’s grave and memory. For community leaders such as sachems, wills were a way of ensuring successors. As Jack Goody notes in “Death and the Interpretation of Culture,” the transfer of goods related in wills not only reveal “collective attitudes toward the other world, beliefs about spiritual beings and the fate of the soul, or indeed bereavement, that is, the individual’s reaction to loss. We can also examine them to throw light upon the relations between members of the social group, whether living or dead” (Goody 5).

could persist after death, either by re-cementing the relationships of the family to community members (for example to one’s minister) or by ensuring proper respect for one’s grave and memory. For community leaders such as sachems, wills were a way of ensuring successors. As Jack Goody notes in “Death and the Interpretation of Culture,” the transfer of goods related in wills not only reveal “collective attitudes toward the other world, beliefs about spiritual beings and the fate of the soul, or indeed bereavement, that is, the individual’s reaction to loss. We can also examine them to throw light upon the relations between members of the social group, whether living or dead” (Goody 5).

In this way, wills also provide important insights into history of the mind (l’historie des mentalités). Because wills such as the one by Naomai Omausah contain a spiritual element, they can be used to assess changing attitudes towards death. French historian M. Vovelle has argued that during the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment caused profound changes in attitudes towards death. Vovelle suggests that people became less confident at the moment of death and more concerned with the physical ramifications of dying (Goody 2-3). It is worth considering whether these anxieties are reflected in either Indian Converts or in the wills from the Vineyard, or whether they were not yet present in the community.

Naomai Omausah’s (Ommaush) will was not written by herself, but by her minister, Zachary Hossueit. Since not all islanders could write, Hossueit often served as a scribe for members of the community. One explanation for the generosity Hossueit receives in Omausah’s will is the community’s gratitude for Hossueit’s successful efforts to keep Wampanoag Israel Amos from buying up Native lands to sell to the English. Omausah was not alone in her gratitude. In 1763 the town of Aquinnah gave Hossueit “the run of hundred sheep, noting how twenty years ago he 'stood by us and bore the big[g]est part of the Charge' in fending off Israel Amos" (Silverman 294-95). Notably, the goods bequeathed by Omausah are all English in nature, although the average household probably would have contained a mixture of Wampanoag and English goods. Wampanoag goods might include mats for sitting, clay pots, baskets, fishing gear, farming tools, bark containers, pipes, and foodstuffs. Common European good included kettles, hatchets and axes, utensils, knives, cloth, clothing, beads, ceramics, firearms, scissors, and other metal objects (Nanpashamet).