Whalesong

Biology 342 Fall 2010 // By Jack Craig & Matt Yee

Adaptive Value

The adaptive of a behavior can be defined as the benefit it confers to the animal which practices it. By the principle of natural selection, behaviors with significant positive effects on the fitness and reproductive capacity of the animal are more likely to appear in the next generation, and thus more likely to eventually manifest throughout the population.

Whales of almost all species express two specific types of vocalization. The first is descriptively referred to as a “click,” while the second is the more well known “song” or whistle. Both serve a number of separate functions with different adaptive values. On the most elemental level, clicks are used for echolocation, and songs for communication, especially with social or copulatopry purpose. The evolution of such an elegant behavior that adresses these fundmental needs of social, aquatic mammals is clearly of the utmost adaptive value. The utility of both types of vocalization is explored more thoroughly below.

Clicks

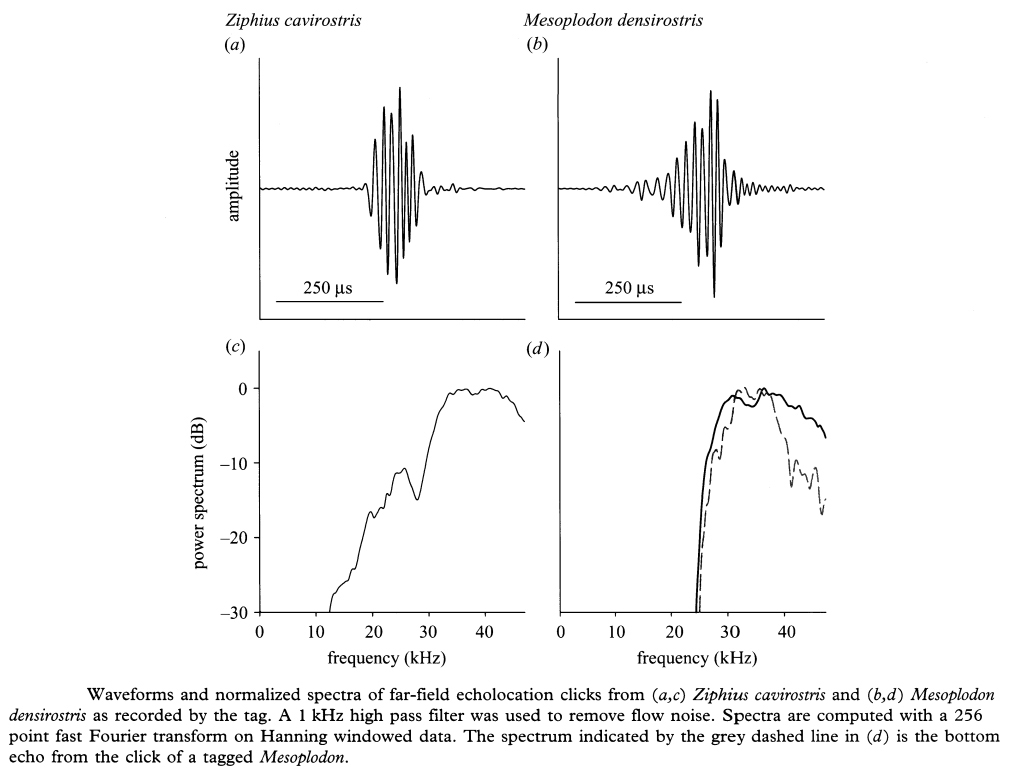

The primary function of the click is echolocation, a good example of which is provided by the beaked whales of the genus Mesoplodon and Ziphius. A 2004 study of these whales by M. Johnson, P. T. Madsen, W. M. X. Zimmer, N. A. Soto and P. L. Tyack using an acoustic recording device revealed that the whales clicked only when diving between 200 and 1267 m. these vocalizations were observed to have no noticeable energy below 20 kHz with a volume in the range of 200-220 dB. Similar patterns of clicking were been observed in the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) by S. L. Watwood, P. J. O. Miller, M. Johnson and P. L. Tyack in 2006, suggesting that the behavior is widespread in toothed whales. The adaptive value of clicking then, can clearly be discerned by the massive benefits echolocation provides to hunting whales.

Below: a figure taken from the beaked whales paper illustrating typical waveforms and frequencies of the echolocation clicks.

Image Source: "Beaked Whales Echolocate on Prey"

Singing

The more recognizable form of whale vocalization is the song or whistle, longer and more intricate that the click, repeated every five to 30 minutes for up to 22 hours at a time, almost exclusively by lone male whales, according to Tyack's 1982 paper, “Differential Response of Humpback Whales, Megaptera novaeangliae, to Playback of Song or Social Sounds.” That paper also revealed that the long songs played by researchers, replicating the song of a lone whale, triggered either approach or avoidance depending on the group of whales tested and proximity of the broadcaster, suggesting a role in mediation of territory and inclusion in a group. Additionally, whales were observed to produce shorter (2-20 second) vocalizations exclusively when part of a group. The adaptive value of these signals comes from the fact that water is an excellent medium for long distance transmission of sound, and being that whales are social animals living across enormous home ranges, the ability to transmit social messages via sound is very useful. Furthermore, because whales, like all mammals, must reproduce sexually and also have a relatively low reproductive rate, it is obviously quite biologically favorable to have adapted a mode of mate location that functions so well over long distances.