Love Dart Shooting in Simultaneously Hermaphroditic Snails

Biology 342 Fall 08

Charlene Grahn and Robin Steitz

PHYLOGENY

Diverse Morphology and Behavior

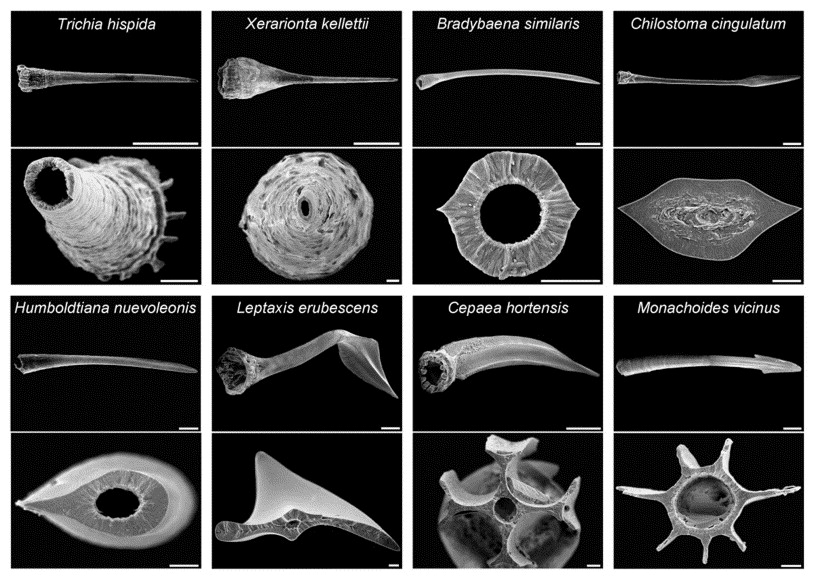

The highly differentiated morphology of love darts evidenced below is a result of several different phylogenetic pathways and specializations within those pathways in hermaphroditic snails. The diversity in dart exchange interactions between species is apparent not only in the morphological structure of the darts but also in the behavioral actions of the snails during mating. The individual mating members of the species E. subnimbosa, for example, stab each other with love darts many times before sperm exchange occurs (Koene 2006). In other dart-shooting species, however, the behavior is not always observed and is considered to be largely optional or unessential for mating. These behavioral and morphological adaptations by the sperm donor role are paralleled by the largely morphological adaptive diversity observable in the sperm receptive organs between species (Koene and Schulenburg 2005). This supports the control theory of adaptive value (see ADAPTATION), which suggests that because these snails are simultaneous hermaphrodites, natural selection will favor those individuals with male reproductive systems that increase the likelihood of their sperm attaining fertilization by overriding the receiver’s cryptic female choice, and will also favor those individuals with female reproductive systems that have morphological adaptations that reduce the impact of these darts on their ability to select sperm (Schilthuizen 2005). Thus we observe the morphological and behavioral diversification that is a result of this adaptive co-evolution that attempts to reconcile the problem of the conflict of interest between gender roles.

"Diversity of love-darts" Koene and Schulenberg 1998. Electron micrographs of the diverse morphologies of love darts. Upper photographs are of the entire love darts and the lower micrographs are of their corresponding cross-section.

"Diversity of love-darts" Koene and Schulenberg 1998. Electron micrographs of the diverse morphologies of love darts. Upper photographs are of the entire love darts and the lower micrographs are of their corresponding cross-section.

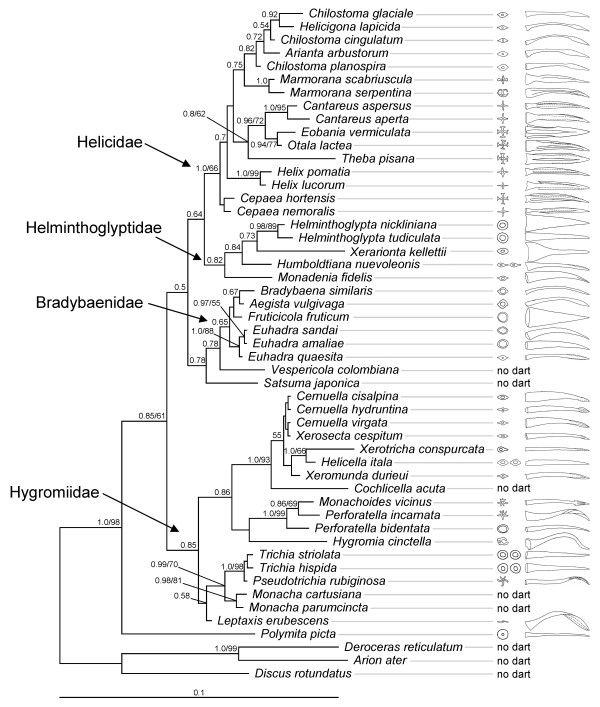

Phylogenetic range of dart-shooting behavior

Throughout the world, dart-shooting occurs in the hermaphroditic snails of three different monophyletic groups (two of which, Helicoidea and Limacoidea, are presumably unrelated), and in eight families within those groups. This information suggests that darts have evolved independently, but phylogenetic data that concerns evolutionary events in snails of the very distant past are rather speculative. However, dart shooting is exclusively found in species that utilize the “face-to-face” method of mating, which involves the intromission of the penises of both individuals during one mating event, as opposed to other species that have unilateral penetration during mating. The dart shooting is never found in species with unilateral penetration, presumably because this disrupts the co-evolutionary cycle that develops between the male and female reproductive systems in species where mating is entirely reciprocal (Davison et al. 2006). In an intensive phylogenetic analysis of the evolution of the physiologies of dart-shooting snails, Koene and Schulenburg found “both repeated and correlated evolution between traits associatd with dart shooting and spermatophore receipt” (Koene and Schulenberg 2005). This important correlation provides a great amount of support for the sexual conflict hypothesis, since it provides evidence for the existence of co-evolution of the reproductive systems in an “arms race” between the different gendered components of the snails.

"Phylogeny of land snails and their love darts" Koene and Schulenberg 1998.

Co-evolution of reproductive systems

In the context of the complex interactions that occur between the sperm donor and the sperm recipient in hermaphroditic snails, the evolution of extreme behaviors such as dart-shooting is relatively understandable. Because the recipient of the sperm is not only capable of storing sperm for long periods of time but also of digesting sperm while mating with several different partners in a display of cryptic female choice, sexual selection favors the donating individual who manipulates these processes in the receiver, and further favors the receiving individual who can overcome these manipulations. Thus the morphologies and behaviors associated with reproduction in dart-shooting snails can be seen as co-evolving, particularly because these two differing and conflicting systems are not only embodied in a single individual but are both displayed by either member of a mating pair during each mating event.