Submissive Behavior

Biology 342 Fall 07

Clare Parker and Natalie Morgenstern

Phylogeny

Old world monkeys are a diverse group. Some members live mostly in the trees, others stay on the ground. They inhabit a wide range of ecological niches. Some, like the macaques, are eat only fruit while others, such as baboons, engage in hunting.

Social Organization

Despite differences in diet and habitat, most, if not all, old world monkeys, live in social groups. A few examples of social organization among some old world monkey species are (all from 14):- Macaques -- large, multi-male groups with important female hierarchies and matrillineages.

- Mangabeys -- single-male or multi-male groups.

- Baboons -- multi-male groups with strong male dominance hierarchies. Hamadryas baboons live in small, single male groups.

- Mandrills -- single male groups that may come together in the dry season. Solitary males common.

- DaBrazza's monkey -- sometimes forms monogamous families.

- Talapoin monkey -- very large groups, little inter-gender interaction for most of the year: single-sex subgroups form.

Most old world monkeys live in multi-male or single male groups. Females usually remain in the group where they were born. They form strong hierarchies based on passed on from mother to daughter (14). (see ontogeny)

In basically any group of old world monkeys, there is a status hierarchy. The hierarchy is determined by who submits to whom in an encounter – if an individual consistently submits to another member of the group, it is considered to be the subordinate individual. The importance and stability of the hierarchy, as well as the level of aggression, varies from species to species. Submissive behaviors are common to all old world monkeys, indicating that they were present in the ancestral species.

Phylogenetic Inertia

Several experiments have been conducted among different species of monkey to determine whether status systems are controlled more by evolutionary history or environment. If status systems are conserved they are said to have high phylogenetic inertia. A trait that is similar in related animals that live in different environments would have high phylogenetic inertia – it would be similar to the ancestral state and there would be little variation across species. A trait that is different in related species that live in different environments has low phylogenetic inertia – it is more dependant on the environment than on the evolutionary history of the species.

Several aspects of social behavior appear to have high phylogenetic inertia. Submission patterns and dominance hierarchies are common in nearly all old world monkeys. However, there are different grades of social organization. In some social organizations, there is a very clear and important hierarchy, in other systems, the hierarchy is less important and dominance is less consistent.

Macaques have high phylogenetic inertia with regards to status systems.

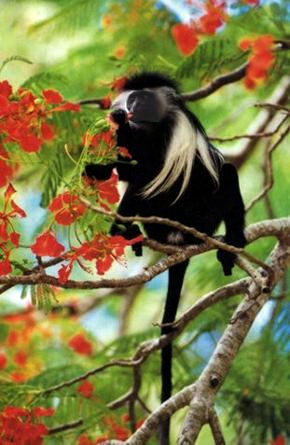

However, a study with colobus monkeys determined that the type of social system had more to do with environment than with evolution. Different, closely related colobus monkeys showed dissimilar social systems depending on environment (7). Macaques appear to have low phylogenetic inertia with regards to social organization.

Status Hierarchies and Agression

The amount of aggression a species has probably affects the importance of the status hierarchy. In more aggressive species, a stronger hierarchy is present. In less aggressive species, adult males may submit to females or juveniles (11). When a species becomes more aggressive, a stronger status hierarchy evolves. Differences in the amount of aggression shown are very species specific and probably influenced by both environment and phylogeny. The more aggression an animal evolves, the more submission must go along with it in order to prevent injury in an encounter.

Black and white colobus monkey; image from Kenyabeach