Manakin Mating Behaviors

- Biology 342 Fall 2016 -

Erin Howell and Morgan Vague

Ontogeny:

Ontogeny is the 2nd of Tinbergen’s 4 questions and refers to the acquisition of behavior, or how a behavior develops over time through learning and growth (Ryan, Wilczynski).

Learning to Dance

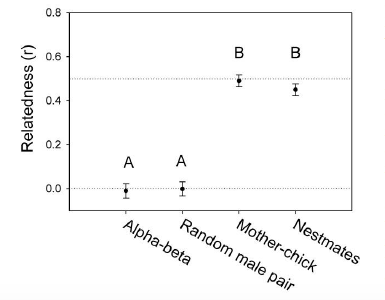

The manakin species has a highly developed social network and dominance hierarchy (McDonald 2007). The long-tailed manakin (Chiroxiphia linearis) have developed a lek mating system where unrelated males cooperate in dual-male song and courtship display (McDonald, 2007). A similar phenomenon exists in lance-tailed manakins, where a designated beta male dances alongside a more dominant alpha male in order to help the alpha male achieve copulation (DuVal, 2007). This is not due to kin selection, which suggests that animals may sacrifice their reproductive success to enhance the reproductive success of a relative and thus perpetuate their genes indirectly. Rather, this duet dancing has been dubbed ‘cooperative’ because the synchronized courtship activity of 2 males enhances the reproductive success of only 1 male, the alpha male (DuVal, 2007).

In lance-tailed manakins, reproductive success is significantly correlated with beta participation in cooperative courtship displays (DuVal, 2012). Many males who did not participate in alpha beta duets had lower reproductive success than those who participated (DuVal, 2012) Males who participated in the beta role were more likely to have future reproductive success after helping the alpha mate (DuVal 2012). This is likely because they become the new alpha males once the original alpha males leave (DuVal 2012). This demonstrates a complex social network helps drive the cooperative courtship behaviors of certain manakin species such as the lance-tailed manakin.

However, not all beta lance-tailed manakin males exhibit increased reproductive success as compared to non-participating ‘non-territorial’ males (DuVal, 2013). Some non-territorial males show higher rates of copulation than beta males who have ascended to an alpha position through an average of 4 long years of cooperative mating (DuVal, 2013). Manakin species are governed by complex social networks. Before forming alpha-beta pairs, male manakins engage in several social interactions with other males that ultimately shape their role and thus their reproductive success within a manakin population (McDonald, 2007). A manakin’s “information centrality”, or how much influence he yields within his population through interactions and displays, is highly correlated to his reproductive success (McDonald, 2007). Thus, a non-alpha male with a high degree of information centrality is more likely to have a higher rate of copulation than a beta male with a low degree of information centrality (McDonald, 2007). Thus, there are several ontological reasons why coordinated cooperative mating displays may have developed in manakin species .