Corvid Vocalizations

Biology 342 Fall 2015

Nathaniel Klein and Sophia McKean

Lifetime Reproductive Fitness

Tinbergen phrased this question as “adaptive value,” but scientists today often refer to “lifetime reproductive fitness.” The ultimate goal of any animal behavior is to help the animal pass on as much of its genetic material as possible, so any behavior that helps the animal to survive (so that it might later reproduce), that helps it reproduce (either directly or by helping the animal get a mate), or that helps the animal have more or healthier children would be said to increase its lifetime reproductive fitness. Corvids are highly social animals, and this means that being able to communicate effectively with others can greatly help increase their lifetime reproductive fitness. Vocalizations can help them do many things, from recognizing familiar or unfamiliar corvids, allowing them to assess if that corvid is a danger or not; to helping them establish dominance, meaning that they don’t have to engage in unnecessary and possibly harmful fights; to identifying the sex of another crow, letting them know if that is a potential mate worth allocating energy to pursuing or not. To understand how these corvids are able to learn how to maximize their lifetime reproductive fitness, it is important to consider the Ontology of the individual animals.

Corvids can encode a huge variety of information in their vocalizations. They have two main types of vocalizations; “kas,” which are just a single note repeated, and “sequential calls,” which involve more than one note. These two main types of calls have different purposes (Kondo & Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 2010). Kas are used for individual identification. In American crows, kas are most useful in identifying the sex of the crow, which is important in finding a mate, as males and females look extremely similar. They can also alert other crows to what is happening in the area; for example, crow kas differ when they are obtaining food versus attacking an intruder. (Exu Anton Mates et al. 2015). A study of jungle crows found that not only do kas help crows identify mates, relatives, and intruders (which are all most relevant when crows are trying to find mates or raise and defend offspring) but that juveniles who live together in large groups before they are of breeding age also recognize each other based on kas. This is important because these groups of juveniles are very fluid, and with individuals often entering or leaving a group, it is important for crows to know who is who (Kondo, Izawa, & Wantanabe 2010).

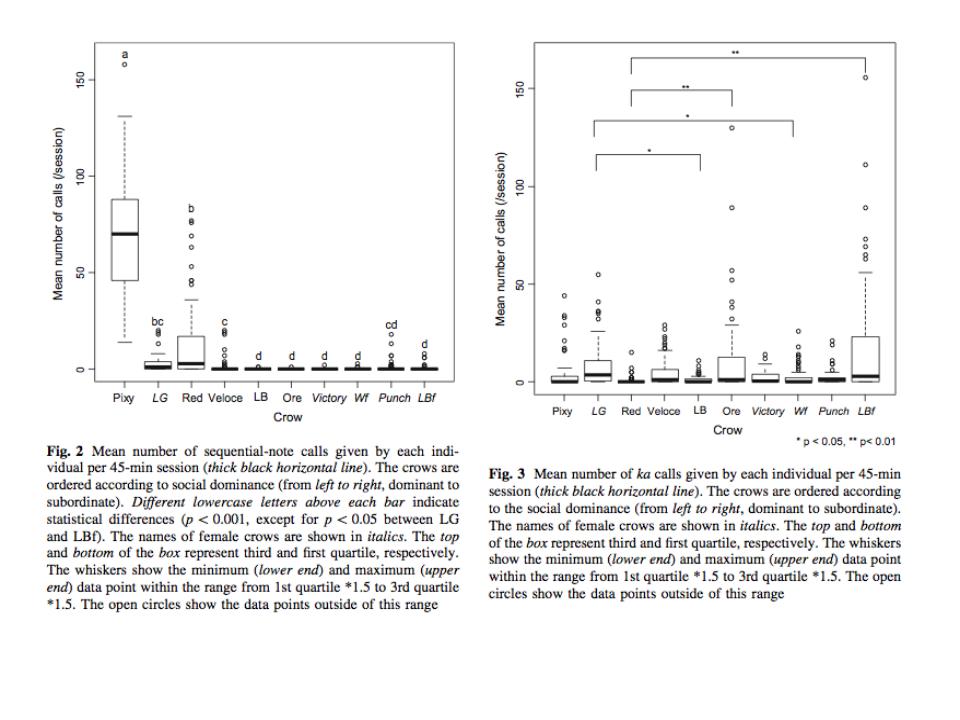

Sequential calls, on the other hand, encode information relating to things like aggression, warning, or food. There are at least twenty documented varieties of sequential calls. In large-billed crows, studies have also found that sequential calls signify dominance status within groups of crows. Dominant individuals vocalize a majority of sequential calls, while less dominant ones vocalize much less (see Figures 2 and 3 below) (Kondo & Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 2015).

Figure 1. These figures were taken from a study that showed that large-billed crows use sequential calls to show their dominance. In both figures, the crows are arranged in the same order, with the most dominant on the far left to the least on the far right. Both are the mean number of vocalizations made by crows in 45 minutes. However, figure 2 is sequential calls, while figure 3 is kas. In figure 2, the three most dominant crows clearly make the biggest number of sequential calls, whereas in figure 3 there is no correlation between kas and dominance. (Kondo & Hiraiwa-Hasegawa 2015).