Kleptoparasitism

Biology 342 Fall 2012

Erin Appleby and Ryan Streur

Watch out! The Seabirds are Feeding!

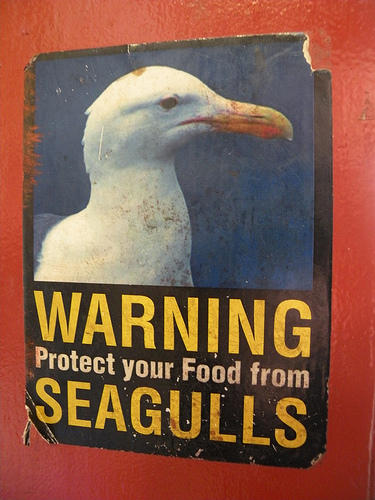

"Thief!" People call seagulls many colorful names as they chase those hungry, aggressive birds from what is left of their idyllic shoreside picnic. “Caution is needed with all outdoor eating throughout the summer in areas where gulls are resident,” warns the States of Jersey website about “Nuisance seagulls”. If you've ever been to the beach and left your lunch unattended, you know this is not a joke.

The Perfect Balance of Brawn and Brain

The behavior of food theft (aka kleptoparasitism) is common in other seabirds as well. Stealing food from another organism not only requires athleticism and agility, but also requires careful planning and decision making. This website explores this thrilling behavior as it presents in seabirds, often focusing on one species as an example. The species of seabird that we mention in this website include: elegant tern, brown pelican, scrub-jay, kermadec petrel, great arctic skua, magnificent frigatebirds, snow petrel, albatrosses, giant petrels, black-legged kittiwakes, roseate terns, thin-billed prions and more.

Using Tingbergen's four categories of inquiry (Tinbergen 1963), we consider:

- What does the variance in food theft behavior across related species reveal about how it evolved? What conditions might have influenced the emergence of the kleptoparasitism over time? (Phylogeny)

- Is kleptoparasitism learned or instinctual? Does it develop in stages and at what point in the organism's life? (Ontogeny)

- What traits do seabirds possess that enables them to steal food? (Mechanism)

- How might kleptoparasitism aid or hinder the seabird's ability to survive and produce as many healthy chicks as possible? (Adaptive Value)

Seabirds must search (or forage) for food sources that are unpredicatbly and patchily distrubuted over vast ranges of ocean. They have an acute sense of smell, rely on their parents to feed them during their slow maturation process, and have relatively few chicks per breeding season. These traits make the occurence of kleptoparasitism in seabirds particularly interesting and special, and help us ask Tinbergen's questions.

What is Kleptoparasitism?

Kleptoparasitism: A foraging strategy in which an animal obtains food items by stealing them from other animals which have procured them at a cost to themself (Brockmann and Barnard 1979, Iyengar 2008). The animal doing the stealing is referred to as a kleptoparasite, and the animal stolen from is the host. To the left, a jaeger (aka arctic skua) is attacking an elegant tern over the San Francisco Bay. The phenomenon of kleptoparasitism is divided into several categories based on:

- Obligate vs. facultative kleptoparasitism

- Obligate: The kleptoparasite derives all of its energy intake from kleptoparasitism.

- Iyengar (2008) and Shealer (2011) disagree about the presence of obligate kleptoparasites among seabirds. Iyengar claims that there have been no obligate kleptoparasites among seabirds whereas Shealer claims that certain species of seabird are obligate kleptoparasites during certain times of the year when food is scarce or during breeding season when more energy is allocated to mating. This disagreement may derive from a difference in the definition of obligate parasite; that is, if Iyengar defines obligate parasite as an organism which gets all the energy over the course of its life through kleptoparastism, and Shealer believes that kleptoparasites can switch between obligate and facultative kleptoparasitism during their lives, it seems reasonable that they would disagree about the phylogeny of obligate kleptoparasitism.

- Facultative: The kleptoparasite has an alternate foraging strategy independent of kleptoparasitism.

- Obligate: The kleptoparasite derives all of its energy intake from kleptoparasitism.

- Interspecific vs Intraspecific kleptoparasitism

- Interspecific: The kleptoparasite steals food from members of other species.

- Intraspecific: the kleptoparasite steals food from members of its own species.

- The host may be aware or unaware of the kleptoparasitism.