Laughter-Like Behavior in Rattus novegicus

Biology 342 Fall 2012

by Anna Fimmel

Phylogeny

The phylogeny of a behavior is how it came to evolve over time. In this case, the evolutionary progress of laughter as a behavior. What shaped the behavior of the rats' ancestors so that they laughed? What other animals laugh?

Rats, Great Apes, Dogs, and Humans All Exhibit Laughter-Like Behavior

Rats are not the only creatures who exhibit ‘laughter.’ Dogs do as well. Dogs laugh when they are tickled, or when they are playing with their owners. Dog laughter might be anxiolytic (reducing anxiety), or, like rat laughter (and most human laughter), indicative of positive affect (Simonet et al., 2005). Below is a picture of a dog that appears to be laughing.

Chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans also laugh. They laugh when tickled (see picture to the right), it appears, for some of the same reasons that other animals do: as a sign of positive affect. Laughter is here defined as a series of similar, repeated vocalizations, expelling air. Their laughter is also physically closer to humans’ than dogs’ or rats’; their breath intake pattern almost matches that of humans (Cosmic Log, 2009). However, these data, too, should be taken with a grain of salt. Great apes may or may not laugh for the same reasons humans laugh, but there is no way to know for sure if they have 'a sense of humor.' Again, one must be careful to avoid the problem of anthropocentrism.

However, Laughter is Not Perfectly Conserved Across These Species

“Differences between laughing “systems” among mammals are reflected by cross-species structural differences in brain regions as well as in vocal architecture… Although brain-imaging studies of human participants watching funny cartoons or listening to jokes reveal the activation of evolutionarily ancient structures such as the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, more recently evolved, “higher-order” structures are also activated, including distributed regions of the frontal cortex. So although nonhuman primates laugh, human humor seems also to involve more specialized cognitive networks that are unshared by other species” (Bering, 2012). Which is to say, animals laugh for different reasons and, according to the evidence gathered so far, humans interpret humor and laugh using far more complex neurological structures.

Every species of animal that has so far been shown to exhibit laughter-like behavior has been a mammal. No phylogenetic trees have so far been drawn connecting dogs, rats, humans, and other great apes with regard to laughter. It is difficult, likewise, to find a phylogenetic tree diagramming the evolution of laughter in a recent common ancestor of rats. Below is a tentative phylogenetic tree relating humans to rats (among other nonhuman animals).

A long time ago, creatures that would eventually become human diverged genetically from the creatures that would become rats. Although we are closer relatives to rats than, say, chickens (both humans and rats are mammals, to name just one similarity), we are not as immediately connected to them as we are to other great apes. Which is to say, although they are not very distant relatives, they are distant enough to where one would need several other evolutionary middlemen to track the evolution of laughter-like behavior from rats (and possibly other animals) to humans.

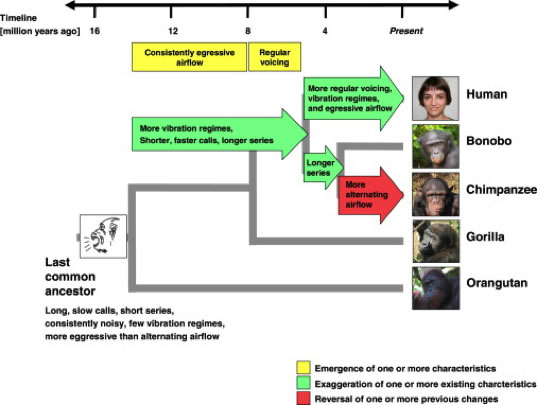

There has, however, been an attempt to phylogenetically map the laughter connection between humans and other great apes. Below is a phylogenetic tree representing the evolution of laughter over time (in millions of years). As one can see, the physical component of laughter is multifaceted, to say nothing of the aforementioned neural correlates.