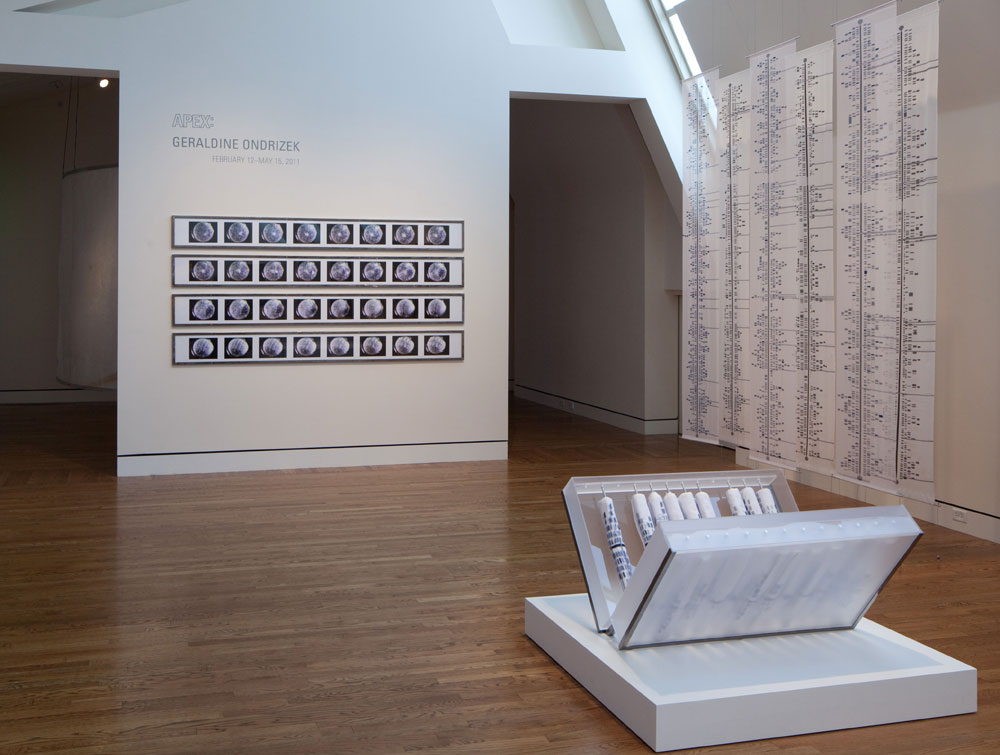

Cellular, Sound Wall and Case Study

Press: Art Ltd Magazine

Catalog (pdf)

WORK IN EXHIBITION

CELLULAR, AND SOUND WALL, 2009

Film-10’x10’, Sound Wall: Hand-made abaca paper, aluminum frame 24’ around x 8’. Digital Film made with Atonics Micro fire digital cameras mounted on Olympus stereomicroscopes. Sound made with AMF, atomic force microscope. Cellular is a film of a blastopore, or a multiple cell embryo. More than 200 hours of still images of each embryo were made with Atonics Micro fire digital cameras mounted on Olympus stereomicroscopes and made into a film using Astor IIDC imaging software. The film Cellular is combined with the recording of the Sound of Cells Dividing. Since 2003, nanotechnology and the AMF (atomic force microscope) have enabled researchers to also touch a cell. Like the blind reading braille or a finger [finger is more common] touching the pulse, the needle of the AMF can touch cells that are less than half the diameter of a human hair. This touch can also record the sound the cell emits when dividing or dying. What we can now listen to within a cell has revolutionized our knowledge of cell division, and the relationships within interior architecture of our body.

CELLULAR FILM STILLS 2009

Archival print, 4’ x 8’ framed in steel and plexiglass

4 rows of film stills depicting gastrulization

CASE STUDY 22 CHROMOSOMES X & Y, 2011

Front panel: Jacquard dye and hand embroidery on dye sublimation, printed sheer silk. Back panel: Laser-printed linen, 20” x 9’

Laser-cut plexiglass box, steel stand. Open 36” x 40” x 24” x 10”, closed 24” x 40”

Collection: The Portland Art Museum

Case Study delineates the human genome, organized into 22 human autosomal chromosomes, the two sex chromosomes X and Y, and corresponding genetic markers and identification, using the NCBI database. In this piece, graphic genetic representations of chromosomes are printed onto sheer synthetic silk, accompanied by the names of genes linked to discernible traits and genetic diseases present in my own extended family. The 24 scrolls are each made of a layer of ultra-sheer silk on top of linen and printed with the graphic representation for all 24 human chromosomes. The cloth has been digitally printed, hand-painted and selectively embroidered to highlight markers on each chromosome. Those highlighted parallel the location of various qualities and anomalies. Each cloth representation of the chromosome is rolled and housed within a large closeable case inscribed with Case Study. The total presentation is meant to appear like the casing for religious scrolls kept in storage for future reading. The scrolls represent the genetic archive that is in each of our bodies. I have highlighted the qualities of the past generation as well as the present.

CURATORS STATEMENT

APEX is an ongoing series of exhibitions featuring emerging and established artists living and working in the Northwest. Presenting contemporary art in the context of the Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Center for Northwest Art, this program continues the museum’s 119-year commitment to exhibiting, collecting, and celebrating the art of the region. The series is supported in part by the Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Endowments for Northwest Art.

Geraldine Ondrizek’s art over the last 20 years has been inspired by scientific investigation. Her architecturally scaled works house medical and biological information, and since 2001 she has collaborated with geneticists and biologists to gather images of human cellular tissue and genetic tests relating to ethnic identity and disease. She appropriates their advanced technology as a departure point for her work, in part because the images stemming from the research are hauntingly beautiful.

After discovering a familial genetic anomaly, Ondrizek began her exploration into a world only recently made manifest by major advances in scientific technology. The three works exhibited in APEX all contain, at their root, her family’s genetic history. Yet her art always transcends the personal; these are evocative illustrations of an opening frontier in the field of genetic research. They are images from an unfolding tale of infinite possibilities that could affect us all, and in Ondrizek’s hands they become powerful works of contemporary art.

These pieces are highly crafted, with their materiality enhancing their metaphorical nature. In the Sound of Cells Dividing (2008–2009), the paper—handmade by the artist—replicates a cell membrane. It has the feel of skin, suggesting the human body, but here the paper membrane is stretched dry over the bones of an aluminum structure. The screen is designed to engage the viewer to physically enter the cell replica and experience its gastrulation firsthand. The screen surrounds Cellular (2009), depicting a multiple-cell embryo. Photographed using a stereomicroscope over 200 hours, the still images were carefully edited and made into a composite film by the artist to show the cell’s early division and growth. The film, which is projected on the wall in a continuous 12-minute loop, morphs before our eyes; in its inflated scale it resembles an undulating moonscape—monumental, not microscopic.

Accompanying the imagery, a rhythmic hum fills and emanates from the gallery. Housed within the paper wall’s semitransparent surface, tiny speakers reproduce the sound of a healthy cell dividing; it is somewhat melodic and dependable with its high-pitched, constantly harmonious drone. But after a few minutes the sound changes and loses rhythm; it is now irritatingly scratchy like a rusty hinge. This is the sound of an unhealthy cell, cancerous, dying. These sounds, originally captured by an atomic force microscope, are being studied for their potential in developing a less invasive approach to diagnosing cancer. If we know that cancer cells produce a sound different from that of healthy cells, we will more readily be able to determine their presence.

The manipulated film and handmade paper are the tools of the artist, the materials becoming metaphorical as well as literal interpretations of the scientific process. The artist describes her relationship to scientists:

I see all three sets of research in this exhibition—Cellular, looking at early egg development; The Sounds of Cells Dividing, a technology to detect cancer; Case Study, mapping genetic markers—to have a parallel mission of looking for visual, physical, and auditory clues of difference to understand what variation within a form indicates. In this way, I find the research scientist to be doing what I do as an artist, pulling out sensory phenomena to look at them more closely. Difference or variation is not a bad thing; rather it is what makes each living thing unique.

Technological advances allow us to sharpen our focus on inner physical worlds, learning to read genetic markers to the point of being able to predict human developmental outcomes. Case Study is inspired by such research. The 24 scrolls of ultra-sheer synthetic silk represent all the human chromosomes, but their soft ethereality suggests a transparent veil that cloaks even as it reveals. Like skin, a veil is a thin layer on top of a body; it hides, protects, and gives an illusion of the softened form below. In this work the veil-like scrolls are used to present—and mask—layers of information, some of it potentially catastrophic. Though deeply immersed in scientific image making, Ondrizek melds current textile technology with age-old handcraft. She meticulously hand dyes the panels with Jacquard silk dyes after they have been digitally printed, then selectively embroiders blocks in the chromosome panel with silklike cotton thread.

Equivalents are prevalent in Ondrizek’s work; the colors, textures, and forms in art and science begin to define each other by example, one in relationship to another. The blue tone on the scrolls is altered from the original digital rendering, made softer for purely aesthetic reasons. Her intent was to place the gray tones on the back panel to suggest a monochromatically printed scientific report and to place the blue “veils” in front, to represent matter tinted for examination. The hidden layer of subtly gray-printed muslin has the respective disease delicately written on each chromosome pattern. The color of the embroidery thread on the outer panel derives from the intense blue of the actual test result from the National Institutes of Health. Genes holding hereditary probability for disease appear darker in the scientific print of the chromosomes, so the artist ominously chose to embroider random blocks with a dark blue thread, an aesthetic decision that mimics meaning.

Ondrizek’s chromosome panels reveal the labyrinth of possibilities in genetically inherited characteristics, mapping strengths and weaknesses that are passed down from one generation to the next to predict a person’s predilection for disease or survival. Each piece in the exhibition reveals patterns with which to detect difference and to see the beauty and strangeness of these differences. While understanding these patterns is crucial and necessary, what to do with this knowledge is open to many ethical questions: Is one egg’s cellular composition inferior or superior to another? Could a human embryo or even a single egg or sperm cell be screened for anomalies and fostered or discarded depending on preference? Should the medical community forecast the likelihood of a person developing a disease such as cancer, Alzheimer’s, or Huntington’s that might not appear until later in life? What is preventative and what is manipulative? Are traits somehow divinely given, or can we see that specific chromosomal patterns determine predictable outcomes? We are at a stage where we can elect to employ microscopic Darwinism, though few of the attendant ethical issues have yet to be sufficiently resolved. It is exciting that an artist can, in her own commanding way, use current medical technology to probe these poignant issues while creating such beautiful, richly stimulating environments.

- Bonnie Laing Malcolmson

The Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Curator of Northwest Art

CREDITS

Sound: Andrew E. Pelling, Assistant Professor of Biophysics, Department of Physics, University of Ottawa, for his sound recording of the cells composed for Dark Side of the Cell, by Anne Niemetz and Andrew Pelling.

Film: Steve Black, professor of Developmental Biology, Reed College, Portland, and Allison Egar, Research Assistant, Developmental Biology, Reed College, for film clips of the cellular mechanics of the gastrulation of a spider egg.

Scrolls: Chromosome images are from the Human Genome Overview, National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine.

Fabrication: James Schmidt, Art Johnson, and Rachel Peterson Schmerge.

Sewing: Azure Akamay, Emily Johnson, Heather MacKenzie, Angela Mestas, and Heather Threadway.

This work has been partially funded by the Stillman Drake Fund and the Deans Fund at Reed College.