IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 92, No. 3: September 2013

Last Lectures: We salute retiring (and not-so-retiring) professors.

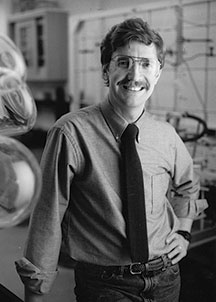

Prof. Patrick McDougal [chemistry, 1990] (continued)

By Nisma Elias ’12

Reed may not have a competitive sports program but that doesn’t mean you couldn’t get a pep talk—especially if you took chemistry.

Prof. Patrick McDougal’s rousing, animated style earned him the nickname “Coach Pat.”

McDougal graduated from the University of Wisconsin, Madison with a PhD in chemistry in 1982. During his time there, he struck up a friendship with classmate Prof. Alan Shusterman [chemistry 1989–]. He taught at Georgia Tech for several years before joining the chemistry faculty at Reed, where he became renowned for his skill at the science (or art) of synthesis of organic molecules. His advanced synthetic organic chemistry class was known as “Advanced Pat.” One of his former students McNeill Kristopher ’92 explained:

“I absolutely adored having Pat as an instructor and as a presence in the department...I was captivated by the way he drew organic molecules on the board—how it seemed impossibly fast and fluid. I remember a particular moment when I was standing at the hood during my junior year, working on an independent study project, and was able to watch Pat holding court in front of a couple of sophomores at the board on the far side of the lab. He was explaining to them the concept of diasterotopic protons and why the two methylene protons of an ethyl group in a chiral molecule have different NMR shifts. This completely blew my mind, but I tried not to openly stare and show my wonderment, since I was the big, bad older student. The little throw-away five-minute lesson stuck with me and I have been using the same explanation and blowing the minds of unsuspecting bachelor, master, and PhD students to this day.”

McDougal’s transition from a successful tenure-track position at Georgia Tech to teaching undergraduates full-time may sound puzzling, only if you didn’t know him. Having a close teacher-student interaction was crucial for him: “I appreciate that at Reed, students enjoy intellectual challenges. What hasn’t changed over the last 20 years is that intellectual curiosity and pedagogy that students have—the lack of change is surprising.”

McDougal’s research was involved with developing new synthetic routes for the construction of biologically active compounds and natural products. Nature produces a wide range of organic molecules that have important biological properties; however, these compounds often have complex structures that make their synthesis difficult. McDougal and his students attempted to find synthetic routes to some of these compounds. His most recent project, in collaboration with a biotech company called Gene Tools, involves finding compounds that will selectively accumulate in small tumors due to the slightly more acidic environment associated with tumor masses.

After 24 years of making sure his students are challenged, while not burning the chemistry building down, McDougal is leaving Reed, on what he acknowledges is somewhat of an early retirement, to try something new that will occupy him mentally and professionally. “Reed is a consuming place, not just for students. I wanted a little space to and figure the next steps out. From what little I have read about retirement planning, I know I have broken the cardinal rule about careful preparation...I guess I see it as just another research project,” he said.

Because of his distinctive pedagogical ethos, McDougal has inspired a whole generation of organic chemists. His legacy as a teacher, mentor and friend, having touched the lives of many, will not be forgotten. As Julia Robinson-Surry’s ’06 wrote:

“I will always remember his loud voice, his enthusiasm, and his tendency to answer questions with questions instead of answers. I teach Organic Chemistry at an early college in NYC and I have developed my own loud voice and my own questions in place of answers. I credit Pat with inspiring me to become an Organic Chemist first, and a passionate teacher second.”

- Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Next Page

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago