Sexual Cannibalism and Mating Behaviors in Mantids

Biology 342 Fall 2010

By: Quinn Langdon and Katherine Thomas

Mechanism

Attraction

Mantid pheromones play an important role in attracting mates (Maxwell et al., 2010). Males are attracted to receptive females when the males are presented with chemical cues, even in the absense of any visual stimuli. However both chemical cues and visual cues are the strongest attractor for males. Female pheromones are an honest signal of fecundity; healthier females attract more males than nutrient deficient females. Accordingly, it was found that hungry females, who are more likely to cannibalize their mates, actually attract fewer mates than well-fed females (Birkhead et al., 1988; Lelito and Brown, 2008).

Mating

Mating involves complex behaviors preformed by both males and females. Approach includes abdomen and leg waving or bending by either adult. Pre-copulatory behaviors typical of male mantids are waving of antennae in the general direction of the female, visual fixation, freezing, and then slow swaying. Males approach slowly with continued swaying until they reach a distance of 3 to 5 centimeters away from the female. At this point, they will leap onto the female’s back. During copulation, the male will touch and stoke the female with his antennae, bend his abdomen, search for the cerci and then mate (Barry et al., 2009).

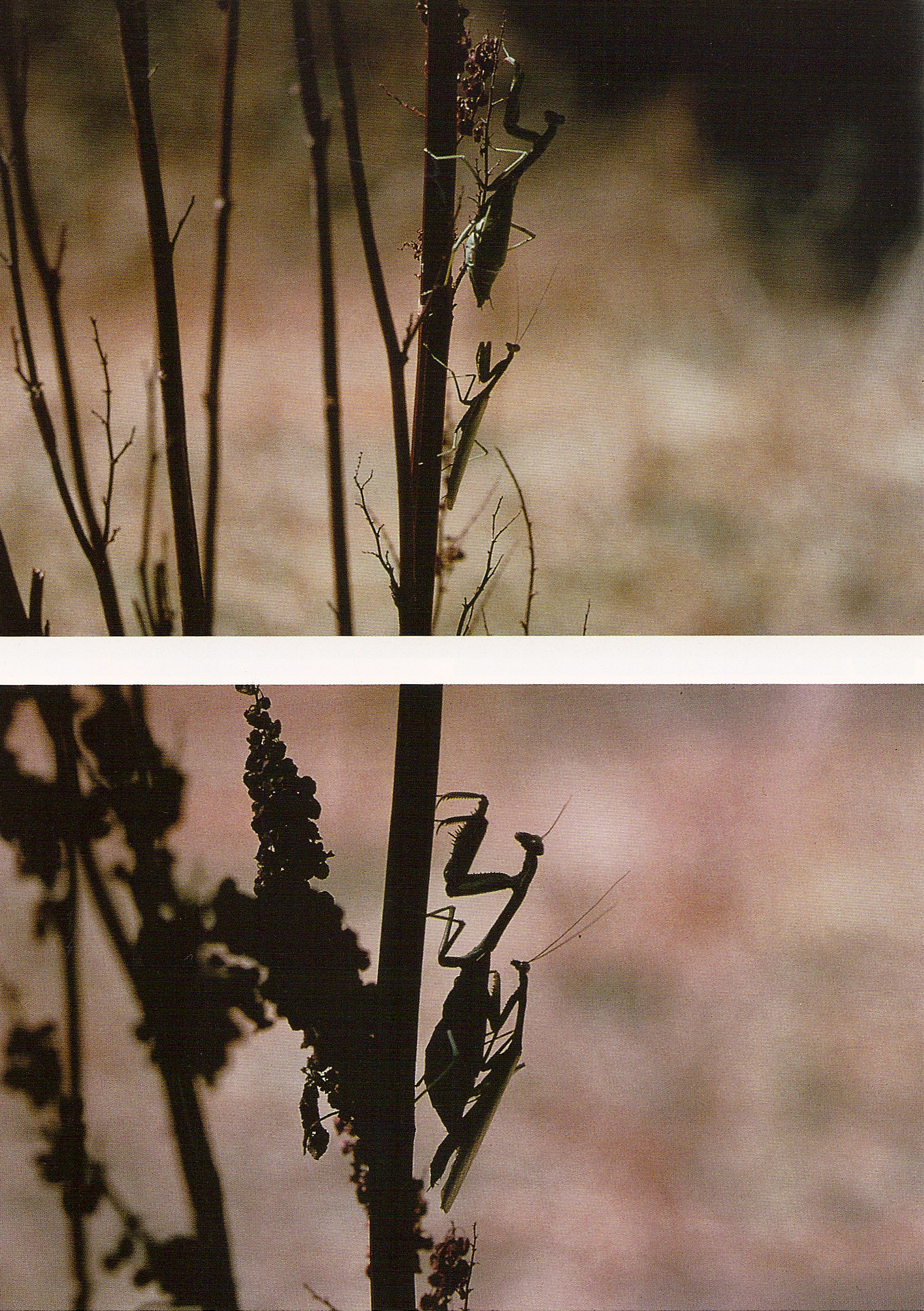

Picture showing praying mantis mating couple. Male's on top, female's on bottom.

Photo Citation: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mantis_religiosa_couple.JPG

Females will attack the male before he mounts, while he is mounted on her back, or after he has dismounted. The attack is usually focused at the male’s head and the female will consume the male in an anterior to posterior direction. Males will generally struggle to break free or continue with the copulation attempt, but chances to escape are usually slim (Barry et al., 2009). Before mounting the attack usually takes the form of a predatory strike, but while mounted, the female can use her foreleg to reach around and pull the male into her mouth. The male can continue to copulate and deliver the spermatphore even while being eaten and even after the head is removed.

If the female sees the male approaching her and is in a position to attack him, she has a greater chance of doing so (Lawrence, 1992). In addition, there have been some observations of cannibalism before the male begins copulation while he is still positioning himself. There have also been observations that the female will attack if the male is not properly positioned, such as when he mounts at a right angle and only clasps her head or the tips of her wings instead of her mesothorax (Lawrence, 1992). Cannibalism has further been seen to occur after mating. For example, a male T. sinensis who remained within 30 cm from his mate was eaten a few hours after mating (Prete, 1999). However, post-copulation cannibalism is more common in lab settings when the male is caged in with the female.

Female eating mate during mating.

Photo Citation: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Praying_Mantis_Sexual_Cannibalism_European-26.jpg

Male Self Preservation

Many males have developed strategies to avoid being cannibalized during mating. For example, when males of the species Mantis religiosa (M. religiosa) see a female, they freeze and approach the females slowly as mantids have a much harder time detecting stationary or very slow moving objects versus rapidly moving prey (Roeder, 1935). His slow approach can take up to an hour. Furthermore, studies have shown that M. religiosa males are more cautious and reluctant to mate with females that are more apt to cannibalize them (hungry females) (Roeder, 1935). In addition, many males employ surprise back mounts of females, a technique that produces lower risk of cannibalism as compared to a front or side mount (Preston-Mafham, 1990). Males also display opportunistic mating where the male will mount the female while she is otherwise occupied by tasks such as eating or grooming. The rate of survival from opportunistic mating is very high. Finally, the males demonstrate quick dismounts and fast escapes that involve either flying away or dropping off of a female to the ground below—a relatively effective strategy as M. religiosa copulations generally happen upside-down in elevated braches (Prete, 1999). These strategies all seem to offer increased chance of remaining unnoticed by the female and hence increase a male’s ability to survive mating (Barry et al., 2009).

Photo of male Stagmonatis limbata preforming a"sneak attack" on a female. (Prete 1999)