Ontogeny

What is ontogeny?

Ontogeny is the developmental history of an organism. In contrast to its genetic underpinnings, ontogeny looks at the external factors, both biotic and abiotic, that influence an organism, morphology and behavior over its lifetime. When looking at the ontogeny of an organism or species, it is important to make a distinction between behaviors that are learned and traits that are genetically predetermined (innate). This can prove useful when studying the way an organism is influenced by, and learns from, its an environment. This distinction is also important in understanding the underlying mechanisms of a behavior.

Size change impacts behavior development

Cephalopod behavior changes drastically over the life course simply because of the considerable change in size these species undergo from hatchling to adult stages. Changes in size of such magnitude demand different foraging and defensive strategies for juveniles than for adults (Hanlon and Messenger).

Body patterning development

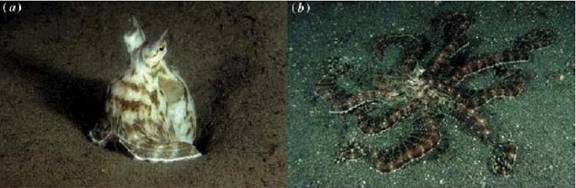

Many cephalopods are born with many of the patterning displays they will possess as adults, but they often need to develop a few more as they grow. For example, hatchling cuttlefishes can produce ten of the total thirteen adult body patterns. Much of this development over the lifetime is due to the change in emphasis of displays from crypsis to communication as the cephalopod grows older. This shift is primarily due to the need to signal for reproduction, though it is still important for adult cuttlefish to be able to hide (Hanlon and Messenger). Furthermore, the bold imitation of cephalopods engaging in mimic behavior implicates conspicuousness as a complementary primary defense tactic to crypsis (Conroy).

A Role for Learning

Learning has been implicated in signaling for many vertebrates (Hanlon and Messenger). In fact, “dynamic mimicry has the unique advantage that it can be employed facultatively, with the octopus adopting a form best suited to the perceived threat at any given time” [9]. This is one distinct advantage of the ability to mimic more than one model, and the cephalopod seems to learn the most adaptive form to assume and flexibly apply that knowledge to the given situation. Thus, “the effect of a potetial predator on body pattern expression during hunting suggests it may be possible to use these changes as a sensitive indicator of ecologically relevant learning” [1].