To Re-Connect the Dots

Can Sheltered Preserves Restore Fragmented Niches of Salmon Cycle?

|

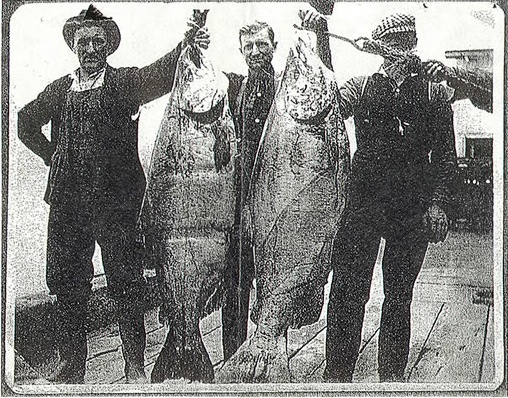

A grainy black and white print from Astoria, Washington, dated 1910, shows three men standing, with deadpan faces, holding two salmon lengthwise. From hooked nose to the tip of their tails, the fish match the men in body length—almost six feet. The photo caption remarks on their weight—116 and 121 pounds, respectively.

These are June Hogs, the famous midsummer Columbia River Chinook stock that spawned 2,650 miles inland along creeks in the Canadian Rockies. Their size has been correlated to the distance they had to swim. Journeying up the river over the course of six months, the fish packed on pounds before heading upstream. Four years after the Grand Coulee Dam cut off their spawning grounds, and the death of multiple fish returns, the June Hog stock, as a whole, went extinct.

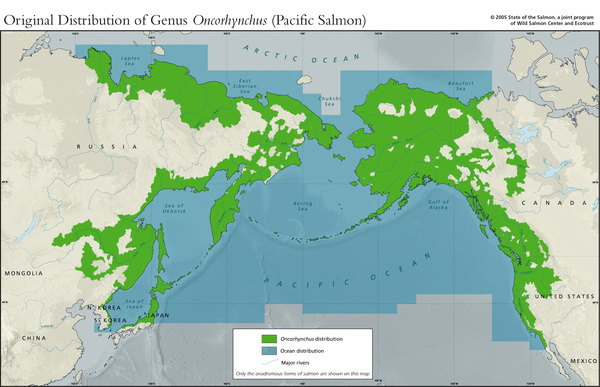

Geography is genome for the Pacific Northwest salmon. As demonstrated in Robin Waples’s map of habitat fragmentation, salmon populations in the Pacific Northwest evolved closely to regional geomorphology over the course of two million years. Without heavy predation, slowing volcanic activity and retreating glaciers, salmon were able to adapt to various riparian niches and colonize inland waterways extensively. The arrival of gold mining, the lumber industry and the construction of dams caused ecological change faster than salmon could adapt. Salmon are dependent on contiguous environmental niches to cycle through their full round of life stages. When the chain breaks, as it did at the Grand Coulee for the June hogs, fish were stranded at one stage or another of their life cycle, fatally compromising succeeding generations.

Salmon are dependent on contiguous environmental niches to cycle through their full round of life stages. When the chain breaks, as it did at the Grand Coulee for the June hogs, fish were stranded at one stage or another of their life cycle, fatally compromising succeeding generations.

Technological fixes for lost habitat, like freshwater hatcheries upstream and oceanic fish farms offshore, further aggravate the problem. While they ensure that fishing boats stay afloat and supermarket freezers are full in the short term, they contribute nothing to the genetic resilience that salmon will need to face mounting environmental challenges.

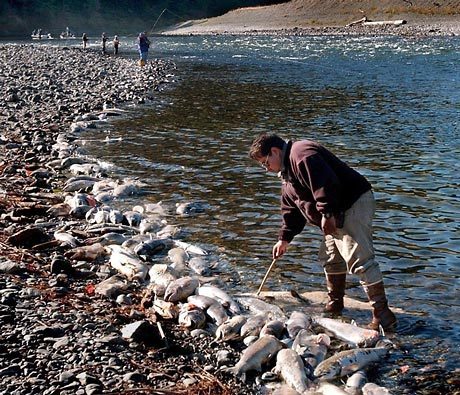

This year, Pacific Marine Fisheries Council advised West Coast Fish and Wildlife office to set a historic ban on salmon fishing. The ban extended across the coasts of Oregon and California, with the exception of a small bubble fishery in Astoria. It was the first ban enforced on the entire six month fishing season—from the spring through the fall, leaving fishermen grounded, salmon prices skyrocketing and millions of dollars doled out as federally sanctioned disaster relief despite a nationwide recession. The reason for the limits on fishing is low returns of Sacramento River fall stock jacks. The low returns were surprising, as the stock is not endangered and mostly hatchery bred. But the upwelling of 2005 had been disastrously weak which stressed salmon smolt that had just arrived on the coast and were trying to adjust from freshwater to saline conditions.

What did the ban mean? Were we at an all-time low?

|

|

Ken Ashley, a well-published Canadian government limnologist, predicts that things are only going to get worse for regional salmon populations as human population growth and water demands explode. According to Ashley, uncontrollable and barely predictable disasters like failed upwelling aside, smaller, incremental manmade issues may be more cause for concern. He cites the 2001 Klamath water crisis is a prime, small scale example. In 2001, there was a drought on the upper Klamath River. Federal regulations temporarily stopped water diversions from the Klamath river to irrigating fields so as to maintain adequate water levels for Endangered Species Act (ESA) protected suckers and coho salmon. Farmers living around the dammed headwater Klamath lake, dependent on lake waters for irrigation, protested the stopped diversions by forcing open irrigation locks.

“When push comes to shove, salmon will lose,” says Ashley. Recently hired as Manager of Special Projects and Business Development for British Columbia Fish and Wildlife, Ashley hopes to implement a restoration plan that will pre-emptively counter this surge in water demands.

“The 11th hour is here,” says Ashley, “ we need to work together or there will be no salmon come 2050.” Ashley wants to officially cordon off hundreds of acres of land as sanctuaries. On these stretches of land, there will be no human contact, few to no hatcheries and heavy regulation on timing of smolt and water release for the few areas where dams and hatcheries are allowed. Conservation funding would also be funneled to the protection of only some species as opposed to the current, across-the-boards, protection given all salmon species under the ESA.

Ashley hopes to set up small entrepenuerial projects like bottled water plants to provide a monetary compensation for setting aside the land. While a bottled water plant does not seem like a big economic contribution from a good sized swath of land or natural resources, high level scientists believe setting aside the land will contribute ecological stability for salmon and therefore provide a long term, regional assurance of an economic good. Setting aside land into salmon parks also creates a clear, social move towards preservation. It makes salmon protection an irreversible and physical institution.

David Bella, an emeritus professor at Oregon State University, proposes “salmon parks”—a series of intricately connected protected waterways like the wild and scenic river or urban green belts with visitation rights similar to those current in national parks.

He sees the establishment of national parks by President Theodore Roosevelt’s administration as a precedent for salmon parks. The establishment of such parks is a matter of legacy. The parks, Bella argues, would serve as a visible and long lasting statement about our societal values in the 21st century.

These intricately connected waterways would show that we now recognize that

1. Human development and interests often get prioritized in times of need, and legal actions passed during these desperate times are often passed on to future generations, then slowly crystalised into irreversable institutions. Land carved aside and institutionalised as Salmon Parks before dire times arrive could ensure a similar concreteness before future, desperate human development choices are made.

2. Salmon conservation cannot be fixed with technology alone. There are too many unknowns. Linear, scientific thinking cannot take care of every relevant factor in maintaining habitat and fish needs at every stage of the life cycle. Setting aside land lets nature take care of a lot of the underlying science and management. Setting aside land acknowledges that the world functions not in components but as an ecosystem at the regional level.

Like Ashley, Bella believes that the ESA is too broad a protection, spreading our conservation funding too thin. He likens the ESA to the dysfunctional American medical system. Today, Bella argues, people don’t put down money unless they really need to and then they go straight to the Emergency room. Instead, we should incrementally contributing to an accessible universal healthcare system.

|

Bella sees two types of authority in the world: The "priestly" tradition and the "prophetic" tradition. The preistly tradition claims authority through knowledge that is linear and scientific. Under this tradition, authority is held and sustained by knowledge gathering experts and administrative bodies. The "prophetic" tradition defined by people, unsanctioned by knowledge or authority, stepping up in times of need. This tradition only occurs in times of need and requires leaders to make un-linear connections, to expand our imagination and change our ways with a few simple actions. "Prophets" are unrealistically hopeful. They ask us to stop thinking linearly, scientifically, and amassing knowledge and in the case of salmon—realistic and therefore cynical.

You can’t predict the future. Given unpredictable large-scale natural phenomena, maybe Ashley, Bella and the Wild Salmon center’s sanctuaries will only slow the inevitable disappearance of Pacific Northwest salmon. Even so, the physical space of the sanctuaries would still be a tangible embodiment of our conservation values that can be passed to future generations.

As Robin Waples, NOAA salmon geneticist said, “after 2 million years of evolution, carefully in synch with the geological shifting of the Pacific Northwest, the future of salmon evolution is now dependent on the societal priorities of the next four human generations."