Manakin Mating Behaviors

- Biology 342 Fall 2016 -

Erin Howell and Morgan Vague

Adaptive Value:

Friend or Foe?

The adaptive value of manakin courtship behavior poses a curious question. If alpha males monopolize mating opportunities, why then do beta males cooperate and sacrifice their own mating success for the success of the alpha? Why do they perform courtship displays in crowded leks where other males are actively courting females? Adaptive value seeks to understand why this occurs.

Manakins engage in lek mating systems. Manakin males conduct courtship displays in “leks”, which are small, elliptical spaces on the forest floor (Isvaran, 2013). Although male manakins are highly territorial, an increase in lek size (a lek with more males performing courtship displays) leads to an increase in female visitors, and thus an increase in opportunities for copulation (Cestari, 2016). This could offer insights into the adaptive value of intensely territorial male manakins performing courtship displays in crowded leks. Although a crowded lek increases competition among males, the manakin species’ highly stratified social hierarchy helps ensure that the most dominant, highly ranked “alpha” males are more successful in copulation, despite the crowd (Cestari, 2016). Additionally, the benefits of a crowded lek outweigh the negative aspect of increased competition, and the social structure of manakins also helps to counterbalance the increased competition present at more crowded leks.

Teamwork

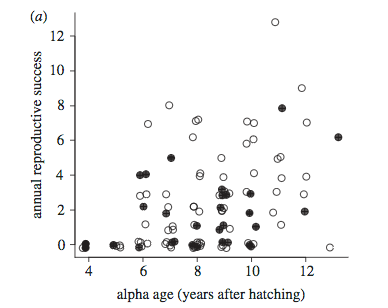

The adaptive value of manakin courtship behavior poses a curious question. If alpha males monopolize mating opportunities, why then do beta males cooperate and sacrifice their own mating success for the success of the alpha? Adaptive value seeks to understand why this occurs. Beta males may choose to engage in an alpha-beta relationship. A beta male paired with an alpha male may gain access to a more coveted lek space that he would never have been able to secure alone (DuVal, 2013). Additionally, delaying an ascent to an alpha position may enable a beta male to survive longer, as ascending to an alpha position carries a large mortality risk (DuVal, 2013). Males who ascend to an alpha position earlier in life (around 4 years after hatching) typically have less reproductive success than males who ascend to alpha positions around 6-10 years after hatching (DuVal, 2013). This may also indicate why males may choose a beta position rather than ascending to the alpha position at an early age.

The Power of Flair

A beta male may also benefit from the ability to practice and thus perfect coordinated courtship displays. This is important because female manakins have been found to judge potential mates based on their ability to perform coordinated courtship displays (Barske, 2011). In fact, the coordinated motor display of song and dance is thought to indicate a male’s cardiovascular fitness to females, because such coordination takes complex motor control and effort (Barske, 2011).