Laughter in Chimpanzees and Humans - Biology 342 Fall 2012

By Yuan Xue, Soso

What Kind of Role Does Laughter Behavior Play Throughout the Development of Primates?

While for most human adults, laughter is elicited by non-physical, verbal social interactions with others; for human infants and chimpanzees, laughter is most commonly induced by physical plays such as tickling. In the context of development of primate infants, laughter is an effective signal to communicate between participants engaged in playful activities. During developmental stages of primates, infants often interact with environmental stimulus and cues in order to promote synaptic changes in motor-sensory neurons that sensitize nervous system for appropriate neural activity during adulthood. Playful activities between infants, or infants and adults present external stimulus for developing infants to better anticipate sensory stimulus and calibrate motor neuron excitations during interactions. Laughter provides a positive feedback for infants to signal to the other participants that the activity elicits pleasure and the associated stress level is endurable. Laughter also effectively prolongs the duration of play in both human and chimpanzee infants (Rothbart, 1973; Matsusaka et al., 2004).

Ontogenesis of Laughter in Chimpanzee Infants

(Matsusaka, 2004)

(Matsusaka, 2004)

This figure is a measured rate of continuation of an "aggressive action" (playful acts such as struggling, mutual tiggling, or round chasing) in response to laughter-like sounds in the context of play (play panting) by the chimpanzee subjects. The y-axis shows the percentage of "aggressive actions" after which the performer continued to perform an "aggressive action" within 10 seconds. Straight lines represent values of each individual chimpanzee performer, and bars represent mean values. Only the data of performers whose numbers of "aggressive actions" with and without the target's play panting were each five or more were analyzed. The numbers of analyzed individuals are in parentheses. *P<0.05, star 0.05<P<0.1. Inf = infants (0-3 years old), Juv = juveniles (4-7 years old), Adol = adolescents (8-13), Mat = mature individuals (over 14 years old).

Mastusaka's study shows that mature (over 14 years old) and infant (0-3 years old) chimpanzees are more likely to continue play actions, defined in this study as succeeding one playful action (e.g. tickling) after another within 10 seconds of interval, after receiving “play panting” (laughter-like behavior) from the targets of the play. This supports the notion that laughter-like behavior is a signal in communication during play. A similar pattern is observed in humans where adult caretakers responded to infant laughters with more play actions (Rothbart, 1973), whereas negative emotions such as crying when expressed by infant recipients significantly reduced the likelihood of continued play actions from the adult performers.

![]()

N.S. = Not Significant (Matsusaka, 2004)

N.S. = Not Significant (Matsusaka, 2004)

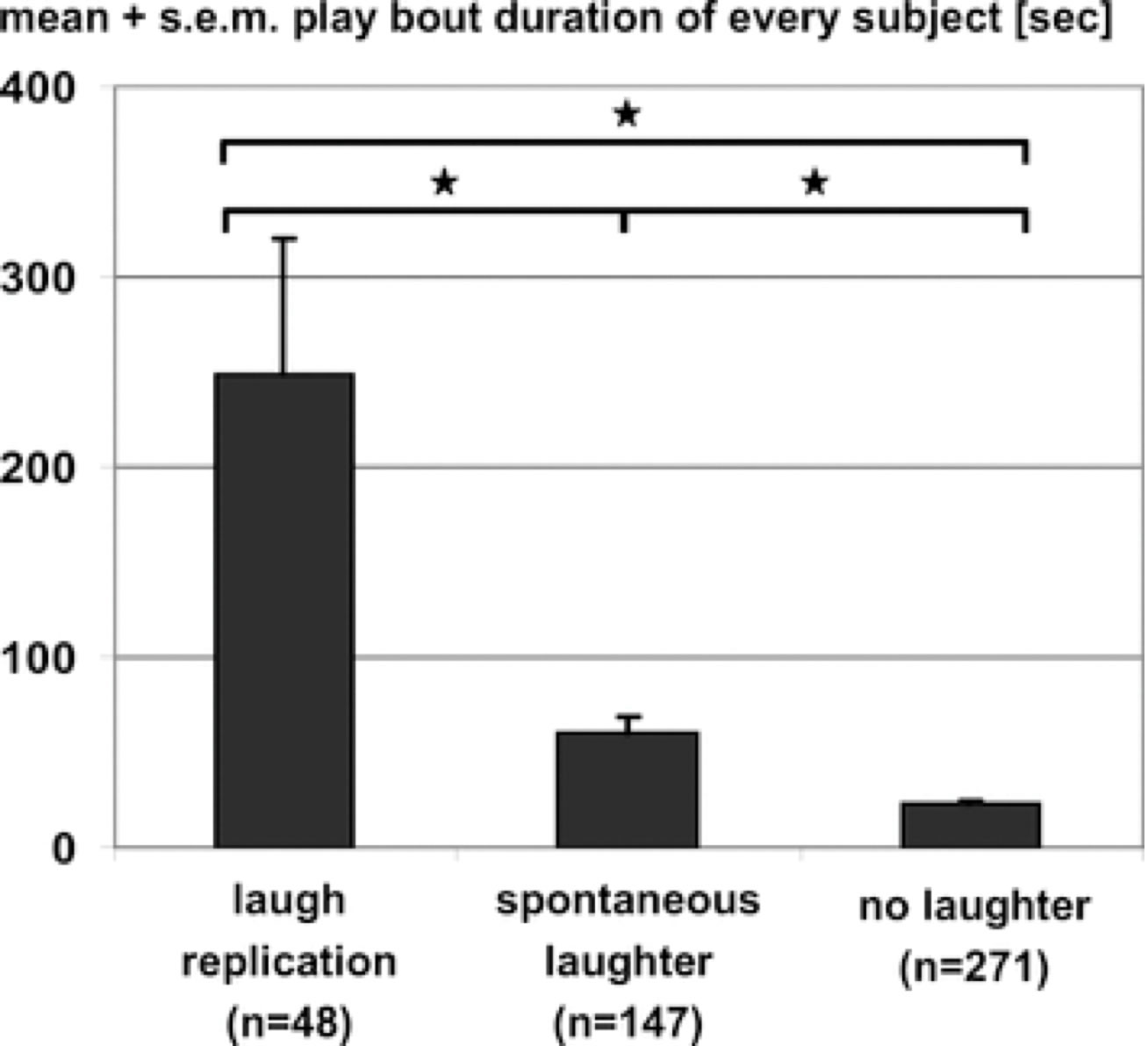

Interestingly, infant chimpanzee recipients (0-3 years old) demonstrated a preference for mature (over 14 years old) playful actions performer in elicitation of laughter-like behavior. Infant chimpanzees performed laughter-like behavior more frequently when interacting with mature chimpanzees; as chimpanzees mature into juveniles, the preference for older performer of play actions diminishes. For both humans and chimpanzees, laughter becomes a more sophisticated mean of communication as they reach juvenile stage. A study observed that juvenile chimpanzees (4-7 years old) elicit laughter-like behavior in mimicry to another chimpanzee's laughter-like behavior, in spite of absence of directed playful actions (Marina, D. et. al, 2011). Some suggest that laughter replication, which is quite common in humans, may be selectively favored in evolution to bolster social bonding between chimpanzee individuals; however, further studies are stillrequired to validate this theory.

Frequency of occurrence for different types of laughter-like behaviors observed in juvenile chimpanzees. *P<0.05, star 0.05<P<0.1. Duration is presented in mean seconds plus standard error of the mean of each subject. Laugh replication is defined as when chimpanzee subject elicits laughter-like behavior in the presence of another individual performing laughter-like behavior without directed physical stimulation. Spontaneous laughter is defined as when chimpanzee subject elicits laughter-like behavior in the absence of another individual performing laughter-like behavior with or without directed physical stimulation. (Marina, 2011)

Ontogenesis of Laughter in Human Infants

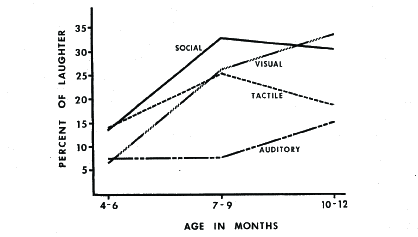

Humans learn to laugh at an early age (14-16 weeks after birth), even before they acquire language production; generally, the laughter is elicited during interactions between the infants and the parents which reinforces the parents interactions (such as tickling) and regulates the intensity and duration of such interactions. An observational study conducted on human infants between 4 months and 12 months old by Sroufe and Wunsch (1972) reveals certain developmental aspects of laughter induction. Based on 300 observational sessions on approximately 160 human infant subjects varying from 4 to 12 months old, they were able to observe age-dependent changes in both the frequency of laughter and the nature of stimuli that elicits laughter in infants. Experimenters, undergraduate students who were trained for 2 months to standardize methods, perform different items of interactions, each grouped into its dominant stimulating pathway, on the infant subjects, and the resulting laugh or no laugh response is recorded.

(Sroufe and Wunsch, 1972)

(Sroufe and Wunsch, 1972)

The infant subjects are collapsed into 3-month groupings. The number presented in the table is the percentage of laughter response elicited by the corresponding stimuli. There is a notable increase in the amount of laughter with age, with a cross-category average of 10%, 37%, and 43% for the 4-6, 7-9, and 10-12-month groups, respectively. Comparing 7-9-month-olds with the 10-12-month-olds, the oldest infants laughed more in response to 12 of 13 visual and social stimulus (p = 0.004, two-tailed sign test), while the 7-9-months olds showed more laughter than the 10-12-months-olds in 9 of 11 auditory and tatile items (p = 0.066, two-tailed sign test). Interestingly, the study shows a trend in human laughter development which emphasizes more on visual and social stimulations than tactile stimulation.

Conclusion

The development of laughter as a mean of communication is observed in both chimpanzees and humans. Although the developmental context differs for chimpanzee and human infants, it is clear that changes in the elicitation of laughter behavior is age-dependent. Older chimpanzees and humans may "laugh" in response to very different stimulus or circumstance than when they were young, but the nature of laughter remains quitessentially the same: it is a communication signal under social context.