the alcoholic vervet monkeys

biology 342 2012

By Sarah Resnick and Amanda Cernegie

MECHANISM

the neurological role in vervet alcoholism:

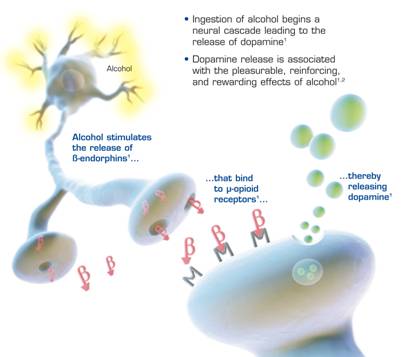

Alcohol, like other drugs of habit, acts through the dopamine (DA) transporter system in the brain. The neurological hormone dopamine acts as a reinforcer to drug stimulation. Studies show in this primate population that chronic alcohol consumption down-regulates the densities of dopamine transporters in the brain, and that this is reversed during times of acute withdrawal. These increased densities in times of sobriety are seen even in abstaining, yet still alcohol-preferring, vervet monkeys, thus leading to the assumption that these altered DA-transporter densities make alcoholism more likely, and can be used to detect and infer future pathology in vulnerable monkeys [7]. Seratonin-transmission dysfunction may also play a role in vulnerability to alcohol, as seen in other primate populations [4].

Alcohol also effects parts of the brain other than the DA system, notably, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Certain acids, such as homovanillic and 5-hydroxyindole acid, found in CSF are seen as inversely correlated with drinking, such that these are seen in significantly low levels in steady and binge drinkers. Based off of these biochemical differences, it has been deduced that patterns of alcohol consumption can be predicted by baseline levels of these acids and other neurotransmitter metabolites in the CSF, even in young primates that have not yet been exposed to alcohol [8].

behavioral and genetic effects as predictors in vervets:

Low behavioral stress responses to novelty are seen as subsequent predictors of increased alcohol consumption in this primate population [1]. This is one point in where the human and primate pathology differs, as humans tend to drink as a sort of coping mechanism for dealing with stress and anxiety. Anxious vervets, on the other hand, tend to avoid alcohol [8], as these monkeys exhibit high stress in novel situations. However, prolonged and chronic exposure can in fact increase the stress/anxiety response in many animals [8].

In human populations, a genetic component to alcoholism is seen in adoptive studies. Children of biological alcoholic parents are more likely to develop the disorder themselves than are children of adoptive alcoholic parents [2]. As the vervet monkey is seen as a model organism for alcoholism in humans [8], the trail of logic can be reversed to assume that genetics effect this behavioral expression in the primate population as well. However, these factors may not be solely due to genetic predisposition, as postnatal provocation surely plays a role as well.