The Immortal Jellyfish

Biology 342 Fall 2011

Eric Van Baak

The Mechanism of the Reverse Life Cycle: They Say You Can't Go Back

How exactly does Turritopsis affect something as major as reversing its entire life cycle? According to Carla' et al.'s morphological study of the metamorphoses, it basically destroys its body.

How exactly does Turritopsis affect something as major as reversing its entire life cycle? According to Carla' et al.'s morphological study of the metamorphoses, it basically destroys its body.

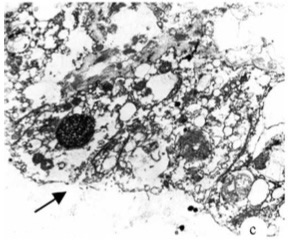

When put under considerable stress, the jellyfish will begin to transdifferentiate those cells composing the outside of the umbrella and the interior vascular system - in this case, changing them from their adult to their larval forms. The process is quite destructive: most organelles rapidly disappear and widespread lysis occurs throughout the body. In the manubrium, the structure containing the jelly's mouth (shown at left; the manubrium is the irregular dark object at the top of the body, with the line through it), cell junctions even begin to break apart. By the time the jellyfish has entered the "four-leaf clover" stage, the majority of the mesoglea, the interior gel making up the body, has leaked out.

As the regression continues, the umbrella begins to disintegrate and the tentacles retract into the body as apoptotic processes continue to break up the medusa shape. Cell junctions continue to break apart as the adult features of the main body are destroyed (cleavage of cell junctions is indicated by the arrow in the image to the right). Eventually the jelly is reduced to a spherical shape, entirely without tentacles, referred to as a "cyst". Almost all of the medusa has been either destroyed completed or severely damaged, although the gonads and striated muscle cells remain largely unaffected. This cyst, which takes the form of two layers of tissue surrounding a center of apoptotic activity, strongly resembles a larval form. Much as jelly larvae find solid surfaces and settle on them to develop into polyps, the cyst, too, will eventually start to exude stolons, structures which will later anchor the polyp to its substrate.

"cyst". Almost all of the medusa has been either destroyed completed or severely damaged, although the gonads and striated muscle cells remain largely unaffected. This cyst, which takes the form of two layers of tissue surrounding a center of apoptotic activity, strongly resembles a larval form. Much as jelly larvae find solid surfaces and settle on them to develop into polyps, the cyst, too, will eventually start to exude stolons, structures which will later anchor the polyp to its substrate.

The need for normal cell division, and the degradation of chromosomes that inevitably accompanies it, is here avoided. By destroying the majority of its own body mass in order to continue living, the organism escapes having to duplicate its existing cells by normal means. In order to continue their lives, most organisms need to continue cell division until, inevitably, telomeres degrade to the point where continued existence of a cell is not possible, and widespread cell death occurs, killing the organism. Here the problem is bypassed, because the continuation of the life cycle past a certain point does not depend on cell division but rather on cell transdifferentiation, a process which does not require the copying of chromosomes and so has no effect on telomere length. Because telomeres are unaffected, aging - as we understand it biologically - does not occur.

(all images taken from Carla' et al.)